Free email delivery

Please sign up for email delivery in the subscription area to the right.

No salesman will call, at least not from us. Maybe from someone else.

Do insects have feelings and consciousness? | Discover Magazine

[Posted by Chuck Almdale]

From the article [Link] by Avery Hurt, 3 Feb 2023:

Science isn’t sure if insects have feelings, but you might want to think twice before stomping a roach or squishing a bee. A growing body of research is making some surprising discoveries about insects. Honeybees have emotional ups and downs. Bumblebees play with toys. Cockroaches have personalities,recognize their relatives and team up to make decisions. Fruit flies experience something very like what we might call fear.

I found this article by googling it, and I think the link will continue to work. The article contains links to other interesting articles.

The original Science article by Frans B.M. De Waal & Kristin Andrews is here, but only the abstract is free to the non-subscriber.

Birding the Southern Oceans and Antarctica, with Alvaro Jaramillo: Zoom Evening Meeting Reminder, Tuesday, 3 February, 7:30 p.m.

You are all invited to the next ZOOM meeting

of Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society

Birding the Southern Oceans and Antactica, with Alvaro Jaramillo.

Zoom Evening Meeting, Tuesday, 3 February, 7:30 p.m.

Zoom waiting room opens 7:15 p.m.

There is no greater wilderness than the Southern Ocean! If you take the globe and look at it from the south pole, there is a huge amount of water there encircling Antarctica, between it and the southern points of the continents and major islands. Seabirds, whales, fish, seals, move through these waters, some like the Wandering Albatross unimpeded by land. The albatross may circle the globe at these latitudes many times in their life. There are islands with hundreds of thousand of penguins, millions of prions (a small seabird) and astounding numbers of fur seals, elephant seals and whales. It is just spellbinding, and these areas are too far away for large cities to have sprung up, at the most some of these islands have a small town or perhaps no one at all on them. The distance you have to travel to get there, the lack of “civilization” and the incredible numbers of birds and other animals is what makes the Southern Ocean so enticing for the naturalist.

I will talk about some of the wonderful birds and wildlife of the subantarctic islands of New Zealand, as well as South America. Places like South Georgia, the Chatham Islands, Macquarie and of course the Antarctic Peninsula. Some of the places and wildlife you see here are life changing, and hopefully I can convey the wonder and beauty that the far south has for you to see.

|

Alvaro Jaramillo, owner of international birding tour company Alvaro’s Adventures, was born in Chile but began birding in Toronto, where he lived as a youth. He was trained in ecology and evolution with a particular interest in bird behavior. Research forays and backpacking trips introduced Alvaro to the riches of the Neotropics, where he has traveled extensively. He is the author of the Birds of Chile, an authoritative yet portable field guide to Chile’s birds. For some time, Alvaro wrote the Identify Yourself column in Bird Watcher’s Digest. He is author of a major New World sparrow chapter for the Handbook of Birds of the World (now Birds of the World), and the new ABA Field Guide to Birds of California. He was granted the Eisenmann Medal by the Linnaean Society of New York, which is awarded occasionally for excellence in ornithology and encouragement of the amateur. He organizes and leads international birding tours, as well as a full schedule of pelagic trips in central California. Alvaro lives with his family in Half Moon Bay, California.

(If the button above doesn’t work for you, see detailed zoom invitation below.)

Meeting ID: 836 5359 5676

Passcode: 944498

One tap mobile

+16694449171,,83653595676#,,,,*944498# US

+16699009128,,83653595676#,,,,*944498# US (San Jose)

Joining Instructions

https://us02web.zoom.us/meetings/83653595676/invitations?signature=hM6nDDbjYBHtrCnNWsJ_YPvj_-cYvCItHxl-xBDt3o4

Cool Times at Malibu Lagoon, 25 Jan. 2026

[By Chuck Almdale; photos by Ray Juncosa]

I could not make it to today’s lagoon walk. Chris & Ruth Tosdevin kindly agreed to lead the trip and sent me a trip list, while Ray sent me some photos. It looked like a lovely day.

Canada Geese have nested on the brushy sand islands in the lagoon since 2019, sometimes one pair, sometimes two, although they were a bit hard to find in 2022.

Red-breasted Mergansers show up every winter, nearly always in single digits. The most we’ve ever had was 25 on 11-23-14, 12-28-24, and 11-27-22. Most look like this bird below as juveniles look much like the adult females. About 1 in 10 look like adult males with a real red breast and dark green head.

Low tide (+1.31 ft) at 8:46 am. In the winter when the outlet to the sea is open, much of the channels consists of mud.

From the the 3rd lookout point near the beach, one can see a large patch of Giant Coreopsis blooming on Boot-heel Island. Pacific Coast Hwy. bridge is behind, then two fruiting palm trees and the coastal range in the distance. Sometimes the fruit from the various palm species introduced to SoCal is unbelievably delicious, if you like squishy fruit. Some people don’t.

Down on Surfrider’s Beach, many of the shorebirds were resting. ZZZzzzzz. Only one of these Sanderlings on the high tide berm seems alert.

This Royal Tern’s bill-edge seems to have fluff attached, and it’s wing coverts appear chaffed. Is this part of the molting process, or is it just being overly-diligent when preening, or was it attacking another bird? Avian mysteries abound.

Black Oystercatchers have shown up three out of the last four months, most likely because these rocks become exposed only during low tides and our walks have coincided with low tide. I once saw a Black Oystercatcher on a sandy beach, not rocks, near Ballona Creek (never at Malibu Lagoon), making that one for the record books.

The group got lucky and spotted a Hutton’s Vireo. According to eBird they’ve been previously spotted at the lagoon nine times, the first time by Katheryn and David Barton on 9-23-84; this was the first time on our monthly field trips. This west coast bird is not abundant anywhere, but they’re far more common in oak woodlands such as in Malibu Creek State Park, a few miles inland, than they are down at the beach.

Another uncommon bird, sighted for the second time in four months on our field trip, but only the 10th time in 46 years, is the Black-throated Gray Warbler. Again, far more common in woodlands. The first one I ever saw was in Yosemite, north of Tuolumne Meadows and deep in the conifer forest, in the summer. Definitely not at the beach.

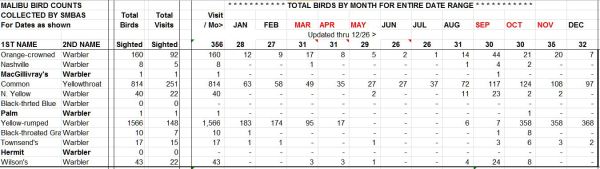

In the above chart we have 2,660 American Wood Warblers in 564 sightings, completely dominated by two species: Yellow-rumped Warbler, which winters at the lagoon, claims 59% of individual warblers and 26% of sightings; Common Yellowthroat has 31% of individuals, but is more frequently sighted (45%). The Yellowthroat breeds at the lagoon, so it’s actual presence should be at or close to 100%, but it’s a fairly skulky bird, usually hidden in reeds or thick brush, and many of our ‘sightings’ are actually ‘heard-only birds.’ If they’re not singing (wichity-wichity-wichity) it’s hard to know they’re there. You can see their relative seasonality and abundance in the numbers above.

The Ospreys lost their favorite roosting and dining pole last summer when it was taken down during construction of a new house in the back row at Malibu Colony. They still use a particular water-edge cypress tree, but they have also begun using one of the poles near the Pacific Coast Highway bridge. Less convenient and definitely noisier, in my estimation.

Malibu Lagoon on eBird as of 1-27-26: 9140 lists, 2957 eBirders, 322 species

Most recent new species seen: Nelson’s Sparrow, 11/29/24 by Femi Faminu (SMBAS member). When the newest species added to the list was seen on a date prior to the most recently seen new species, there is no way I can find to easily determine what that bird is. Another minor nit to pick about eBird.

Birds new for the season: Nanday Parakeet, Hutton’s Vireo, Black-throated Gray Warbler. “New for the season” means it has been three or more months since last recorded on our trips.

Many, many thanks to photographer Ray Juncosa.

Upcoming SMBAS scheduled field trips; no reservations or Covid card necessary unless specifically mentioned:

- Madrona Marsh, Sat. Feb 14, time to be arranged, check blog

- Malibu Lagoon, Sun. Feb. 22, 8:30 (adults) & 10 am (parents & kids)

- Sepulveda Basin, Sat. Mar 10, 8:00

- These and any other trips we announce for the foreseeable future will depend upon expected status of the Covid/flu/etc. pandemic, not to mention landslides, fires, local flooding and atmospheric rivers at trip time. Any trip announced may be canceled shortly before trip date if it seems necessary. By now any other comments should be superfluous.

- Link to Programs & Field Trip schedule.

The next SMBAS Zoom program: Tuesday, February 3, 7:30pm; Birding the Southern Oceans and Antarctica, with Alvaro Jaramillo..

The SMBAS 10 a.m. Parent’s & Kids Birdwalk has again resumed, with ten guests on 25 Jan 2026. Reservations not necessary for families, but for groups (scouts, etc.), please call Jean (213-522-0062).

Links: Unusual birds at Malibu Lagoon

9/23/02 Aerial photo of Malibu Lagoon

Aerial ‘film’ flying north over lagoon

More recent aerial photo

Prior checklists:

2025: Jan-June

2023: Jan-June, July-Dec 2024: Jan-June, July-Dec

2021: Jan-July, July-Dec 2022: Jan-June, July-Dec

2020: Jan-July, July-Dec 2019: Jan-June, July-Dec

2018: Jan-June, July-Dec 2017: Jan-June, July-Dec

2016: Jan-June, July-Dec 2015: Jan-May, July-Dec

2014: Jan-July, July-Dec 2013: Jan-June, July-Dec

2012: Jan-June, July-Dec2011: Jan-June, July-Dec

2010: Jan-June, July-Dec 2009: Jan-June, July-Dec

The 10-year comparison summaries created during the Lagoon Reconfiguration Project period, remain available—despite numerous complaints—on our Lagoon Project Bird Census Page. Very briefly summarized, the results unexpectedly indicate that avian species diversification and numbers improved slightly during the restoration period June’12-June’14.

Many thanks to Marie Barnidge-McIntyre, Femi Faminu, Lu Plauzoles, Chris & Ruth Tosdevin and others for contributions made to this month’s census counts.

The species list below was re-sequenced as of 12/31/25 to agree with the eBird sequence. If part of the right side of the chart below is hidden, there’s a slider button inconveniently located at the bottom end of the list. The numbers 1-9 left of the species names are keyed to the nine categories of birds at the bottom. Updated lagoon bird check lists can be downloaded here.

[Chuck Almdale]

| Malibu Census 2025-26 | 8/24 | 9/28 | 10/26 | 11/23 | 12/28 | 1/25 | |

| Temperature | 68-75 | 65-69 | 58-65 | 59-65 | 60-69 | 47-55 | |

| Tide Lo/Hi Height | H+4.74 | H+4.54 | H+5.02 | H+5.46 | L+1.35 | L+1.31 | |

| Tide Time | 1102 | 1244 | 1125 | 0939 | 1047 | 0846 | |

| 1 | Brant (Black) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 | Canada Goose | 12 | 14 | 3 | |||

| 1 | Northern Shoveler | 4 | |||||

| 1 | Gadwall | 19 | 6 | 14 | 20 | 34 | |

| 1 | American Wigeon | 15 | 4 | ||||

| 1 | Mallard | 14 | 7 | 26 | 1 | 12 | 5 |

| 1 | Green-winged Teal | 5 | 11 | ||||

| 1 | Ring-necked Duck | 1 | |||||

| 1 | Surf Scoter | 10 | 2 | 22 | 4 | 3 | |

| 1 | Bufflehead | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 1 | Red-breasted Merganser | 2 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 1 | Ruddy Duck | 1 | 5 | 11 | |||

| 2 | Feral Pigeon | 4 | 6 | 5 | |||

| 2 | Mourning Dove | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | Anna’s Hummingbird | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 2 | Allen’s Hummingbird | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | Sora | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | American Coot | 4 | 31 | 4 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| 4 | Black Oystercatcher | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 4 | Black-bellied Plover | 49 | 55 | 88 | 64 | 62 | 34 |

| 4 | Killdeer | 9 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | Semipalmated Plover | 1 | |||||

| 4 | Snowy Plover | 17 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 7 | 17 |

| 4 | Hudsonian Whimbrel | 12 | 3 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | Marbled Godwit | 21 | 8 | 10 | 3 | ||

| 4 | Spotted Sandpiper | 1 | |||||

| 4 | Willet | 10 | 14 | 20 | 7 | 7 | |

| 4 | Ruddy Turnstone | 1 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | Sanderling | 1 | 13 | 23 | 14 | 35 | |

| 4 | Dunlin | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Least Sandpiper | 4 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 20 |

| 4 | Western Sandpiper | 14 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 5 | Sabine’s Gull | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Bonaparte’s Gull | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Heermann’s Gull | 10 | 38 | 2 | 49 | 10 | |

| 5 | Short-billed Gull | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Ring-billed Gull | 4 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 17 |

| 5 | Western Gull | 115 | 61 | 35 | 55 | 85 | 45 |

| 5 | American Herring Gull | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 5 | California Gull | 4 | 10 | 116 | 410 | 650 | 275 |

| 5 | Caspian Tern | 2 | |||||

| 5 | Forster’s Tern | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Elegant Tern | 70 | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 5 | Royal Tern | 135 | 12 | 2 | 22 | 25 | 12 |

| 6 | Pied-billed Grebe | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| 6 | Horned Grebe | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Eared Grebe | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 6 | Western Grebe | 30 | 8 | 10 | 45 | ||

| 6 | Clark’s Grebe | 2 | |||||

| 6 | Red-throated Loon | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 6 | Pacific Loon | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Brandt’s Cormorant | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 35 | |

| 6 | Pelagic Cormorant | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| 6 | Double-crested Cormorant | 74 | 49 | 28 | 38 | 17 | 28 |

| 6 | White-faced Ibis | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Yellow-crowned Night-Heron | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Black-crowned Night-Heron | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 6 | Snowy Egret | 10 | 5 | 34 | 30 | 11 | 3 |

| 6 | Green Heron | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 6 | Great Egret | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | Great Blue Heron | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 6 | Brown Pelican | 32 | 45 | 138 | 13 | 3 | 13 |

| 7 | Turkey Vulture | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 7 | Osprey | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 7 | Cooper’s Hawk | 1 | |||||

| 7 | Red-shouldered Hawk | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Red-tailed Hawk | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| 8 | Belted Kingfisher | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 8 | Nuttall’s Woodpecker | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Nanday Parakeet | 20 | 9 | 2 | |||

| 9 | Black Phoebe | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | Say’s Phoebe | 1 | |||||

| 9 | Hutton’s Vireo | 1 | |||||

| 9 | California Scrub-Jay | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 9 | American Crow | 8 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 11 |

| 9 | Common Raven | 1 | |||||

| 9 | Oak Titmouse | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 9 | No. Rough-winged Swallow | 2 | |||||

| 9 | Barn Swallow | 40 | 4 | ||||

| 9 | Bushtit | 20 | 9 | 35 | 4 | 19 | 20 |

| 9 | Wrentit | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | Swinhoe’s White-eye | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Blue-gray Gnatcatcher | 2 | |||||

| 9 | Northern House Wren | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9 | Marsh Wren | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Bewick’s Wren | 2 | |||||

| 9 | European Starling | 35 | 2 | 6 | 30 | 1 | |

| 9 | Northern Mockingbird | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Western Bluebird | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Hermit Thrush | 2 | |||||

| 9 | Scaly-breasted Munia | 7 | |||||

| 9 | House Finch | 12 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 7 |

| 9 | Lesser Goldfinch | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||

| 9 | American Goldfinch | 4 | |||||

| 9 | Dark-eyed Junco | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 9 | White-crowned Sparrow | 2 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 6 | |

| 9 | Savannah Sparrow | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Song Sparrow | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 9 | California Towhee | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| 9 | Western Meadowlark | 2 | |||||

| 9 | Great-tailed Grackle | 23 | 6 | 16 | 3 | 10 | |

| 9 | Orange-crowned Warbler | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | Common Yellowthroat | 4 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | Yellow-rumped Warbler | 2 | 25 | 10 | 8 | 6 | |

| 9 | Black-throated Gray Warbler | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Totals Birds by Type | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | |

| 1 | Waterfowl & Quail | 33 | 25 | 28 | 61 | 95 | 67 |

| 2 | Doves, Swifts & Hummers | 11 | 14 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 3 |

| 3 | Rails & Coots | 4 | 32 | 4 | 26 | 25 | 50 |

| 4 | Shorebirds | 93 | 130 | 219 | 185 | 123 | 128 |

| 5 | Gulls & Terns | 341 | 127 | 164 | 547 | 777 | 349 |

| 6 | Grebe, Loon, Heron, Pelican | 135 | 117 | 259 | 111 | 59 | 134 |

| 7 | Hawks & Falcons | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | Kingfisher, Peckers & Parrots | 1 | 21 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | Passerines | 141 | 82 | 122 | 122 | 91 | 86 |

| Totals Birds | 761 | 553 | 816 | 1065 | 1185 | 825 | |

| Total Species by Group | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | |

| 1 | Waterfowl & Quail | 2 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 8 |

| 2 | Doves, Swifts & Hummers | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | Rails & Coots | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Shorebirds | 7 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| 5 | Gulls & Terns | 8 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| 6 | Grebe, Loon, Heron, Pelican | 12 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 9 |

| 7 | Hawks & Falcons | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | Kingfisher, Peckers & Parrots | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | Passerines | 16 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 17 |

| Totals Species – 105 | 53 | 64 | 61 | 71 | 69 | 55 |

Birding the Southern Oceans and Antarctica, with Alvaro Jaramillo: Zoom Evening Meeting, Tuesday, 3 February, 7:30 p.m.

You are all invited to the next ZOOM meeting

of Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society

Birding the Southern Oceans and Antactica, with Alvaro Jaramillo.

Zoom Evening Meeting, Tuesday, 3 February, 7:30 p.m.

Zoom waiting room opens 7:15 p.m.

There is no greater wilderness than the Southern Ocean! If you take the globe and look at it from the south pole, there is a huge amount of water there encircling Antarctica, between it and the southern points of the continents and major islands. Seabirds, whales, fish, seals, move through these waters, some like the Wandering Albatross unimpeded by land. The albatross may circle the globe at these latitudes many times in their life. There are islands with hundreds of thousand of penguins, millions of prions (a small seabird) and astounding numbers of fur seals, elephant seals and whales. It is just spellbinding, and these areas are too far away for large cities to have sprung up, at the most some of these islands have a small town or perhaps no one at all on them. The distance you have to travel to get there, the lack of “civilization” and the incredible numbers of birds and other animals is what makes the Southern Ocean so enticing for the naturalist.

I will talk about some of the wonderful birds and wildlife of the subantarctic islands of New Zealand, as well as South America. Places like South Georgia, the Chatham Islands, Macquarie and of course the Antarctic Peninsula. Some of the places and wildlife you see here are life changing, and hopefully I can convey the wonder and beauty that the far south has for you to see.

|

Alvaro Jaramillo, owner of international birding tour company Alvaro’s Adventures, was born in Chile but began birding in Toronto, where he lived as a youth. He was trained in ecology and evolution with a particular interest in bird behavior. Research forays and backpacking trips introduced Alvaro to the riches of the Neotropics, where he has traveled extensively. He is the author of the Birds of Chile, an authoritative yet portable field guide to Chile’s birds. For some time, Alvaro wrote the Identify Yourself column in Bird Watcher’s Digest. He is author of a major New World sparrow chapter for the Handbook of Birds of the World (now Birds of the World), and the new ABA Field Guide to Birds of California. He was granted the Eisenmann Medal by the Linnaean Society of New York, which is awarded occasionally for excellence in ornithology and encouragement of the amateur. He organizes and leads international birding tours, as well as a full schedule of pelagic trips in central California. Alvaro lives with his family in Half Moon Bay, California.

(If the button above doesn’t work for you, see detailed zoom invitation below.)

Meeting ID: 836 5359 5676

Passcode: 944498

One tap mobile

+16694449171,,83653595676#,,,,*944498# US

+16699009128,,83653595676#,,,,*944498# US (San Jose)

Joining Instructions

https://us02web.zoom.us/meetings/83653595676/invitations?signature=hM6nDDbjYBHtrCnNWsJ_YPvj_-cYvCItHxl-xBDt3o4

[Posted by Chuck Almdale]

Pacific Coast Highway: As of this moment, things seem fine. No rain, mostly sunny, low lagoon water level, cool-ish enough to keep the beach uncrowded.

Special Attractions: Like dinosaurs? Want to see a dinosaur? Then come. Birds are small dinosaurs, we now know, the last of their kind. Think about that.

The depth of winter and loads of birds. It’s frightening how many there are. I don’t even want to think about it! 60 to 75 species likely. A quiet beach on a cool, quiet day. Dress in layers for cool weather and mild breeze. It’s easier to take something off than put on what you didn’t bring.`

(Lillian Johnson 1-30-25)

Some of the great birds we’ve had in January are:

American Wigeon, Green-winged Teal, Lesser Scaup, Surf Scoter, Long-tailed Duck, Bufflehead, Red-breasted Merganser, Red-throated, Pacific & Common Loons, Horned, Eared & Western Grebes, Brandt’s & Pelagic Cormorants, Osprey, Red-shouldered & Red-tailed Hawks, Peregrine Falcon, Snowy Plover, Black Oystercatcher, American Avocet, Spotted Sandpiper, Marbled Godwit, Heermann’s, Herring & Glaucous-winged Gulls, Royal & Forster’s Terns, Black Skimmer, Anna’s & Allen’s Hummingbirds, Belted Kingfisher, Black & Say’s Phoebes, Bewick’s & House Wrens, Common Yellowthroat, Spotted Towhee, Song & Lincoln’s Sparrow, Red-winged Blackbird, Great-tailed Grackle, Lesser & American Goldfinches. A googolplex of birds! Perhaps two googolplexes of birds!

If you arrive early you may perchance to espy a trewloue of turtuldowẏs.

We will have a guest trip leader(s). Come and find out who it could be.

Weather prediction as of 22 January:

Sunny, cool. Temp: 52-64°, Wind: ENE 7>9 mph, Clouds: 18>48%, rain: 0%

Tide: mid, falling to low: Low: 1.31 ft. @ 8:46am; High: +4.69 ft. @ 1:42am 25 Jan.

Dec 28 trip report link

Adult Walk 8:30 a.m., 4th Sunday of every month. Adults, teens and children you deem mature enough to be with adults. Beginners and experienced, 2-3 hours, meeting at the metal-shaded viewing area between parking lot and channel. Species range from 35 in June to 60-75 during migrations and winter. We move slowly and check everything as we move along. When lagoon outlet is closed we may continue east around the lagoon to Adamson House. We put out special effort to make our monthly Malibu Lagoon walks attractive to first-time and beginning birdwatchers. So please, if you are at all worried about coming on a trip and embarrassing yourself because of all the experts, we remember our first trips too. Someone showed us the birds; now it’s our turn. Bring your birding questions.

Children and Parents Walk, 10:00 a.m., 4th Sunday of every month: One hour session, meeting at the metal-shaded viewing area between parking lot and channel. We start at 10:00 for a shorter walk and to allow time for families to get it together on a sleepy Sunday morning. Our leaders are experienced with kids so please bring them to the beach! We have an ample supply of binoculars that children can use without striking terror into their parents. We want to see families enjoying nature. (If you have a Scout Troop or other group of more than seven people, you must call Jean (213-522-0062) to make sure we have enough binoculars, docents and sand.)

Directions: Malibu Lagoon is at the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) and Cross Creek Road, west of Malibu Pier and the bridge, 15 miles west of Santa Monica via PCH. We gather in the metal-shaded area near the parking lot. Look around for people wearing binoculars. Neither Google Maps nor the State Park website supply a street address for the parking lot. The address they DO supply is for Adamson House which is just east of the Malibu Creek bridge.

Parking: Parking machine in the lagoon lot: 1 hr $3; 2 hrs $6; 3 hrs $9, all day $12 ($11 seniors); credit cards accepted. Annual passes accepted. You may also park (read the signs carefully) either along PCH west of Cross Creek Road, on Cross Creek Road, or on Civic Center Way north (inland) of the shopping center. Lagoon parking in shopping center lots is not permitted.

[Written & posted by Chuck Almdale]