Bible Birds

This page was originally published in August-October of 2016.

It has been altered to fit a single-page structure.

Part I – What About that Dove? & Factoid: Gilgamesh

Part II – Sandgrouse or Quail? & Factoid: YHVH [יְהוָ֖ה] [Yahweh]

Part III – Junglefowl in Judea! & Factoid: New Testament Koine Greek

Part IV – Birds that Sow, Reap and Store & Factoid: Whence Jesus (Ἰησοῦς)

Part V – The Friendly Ravens & Factoid: The Bar-Abbas Mystery

Part VI – The Humble Hoopoe & Factoid: Catching “Forty” Winks

Part VII – The Wise Hoopoe & Factoid: On “On”

Part VIII –Don’t Eat That Bird! Part 1 & Factoid: Of “Of”

Part IX – Don’t Eat that Bird! Part 2 & Factoid: Seeing “Red”

Part X – Don’t Eat that Bird! The Last Bite & Factoid: Problems of Translation

[Chuck Almdale]

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study I:

What About That Dove?

Whatever one may think of the bible, it was inarguably written long ago by humans not significantly different than us, who wrote about what they knew and what they imagined, just as we do today. Any mention of a bird means – at a minimum – the writers had noticed them, however little they might have to say about them, or however accurate it might be. In this series, we begin with what the bible says about birds, to which we add what we’ve learned over the centuries since then, to see if we can uncover anything new and interesting. Each essay begins with a citation; we start in the beginning, with Genesis, the first book of the bible.

Cartoon by Charles Addams

“After forty days Noah opened the trap-door that he had made in the ark, and released a raven to see whether the water had subsided, but the bird continued flying to and fro until the water on the earth had dried up. ”

Genesis 8:6-7 New English Bible

Little is said about this raven [עֹרֵב – oreb], not even whether it ever returned. One suspects it didn’t. Ravens usually have their own agenda. The raven in question was almost certainly the Common Raven (Corvus corax), the same species we find today across North America and Eurasia. We’ll revisit ravens in general, and this citation in particular, in a later episode and move on to the more useful – to Noah, and to humanity by extension – dove.

“Noah waited for seven days, and then he released a dove (יוֹנִים – yonah) from the ark to see whether the water on the earth had subsided further. But the dove could find no place to settle, and so she came back to him in the ark, because there was water over the whole surface of the earth. Noah stretched out his hand, caught her and took her into the ark. He waited another seven days and again released the dove from the ark. She came back to him towards evening with a newly plucked olive leaf in her beak…He waited yet another seven days and released the dove, but she never came back.” Genesis 8:8-12 New English Bible

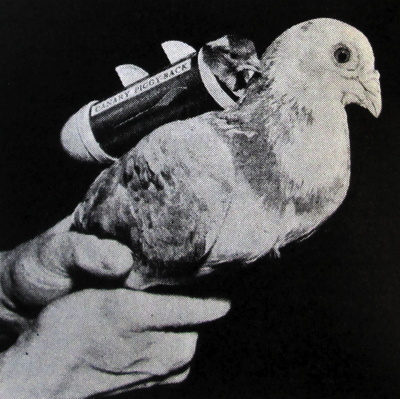

Why would Noah choose to send out a dove, of all birds, and what kind of dove was it? Ornithologists currently recognize 330 species of pigeons and doves grouped into 45 genera, so deciding which dove it was could be daunting. [All 330 species were presumably on the ark, along with the rest of the 10,000+ avian species.] Our story describes Noah’s ark as eventually coming to rest on Mt. Ararat, 16,945 feet high, 14,000-15,000 feet above the surrounding Armenian plain of eastern Turkey. We’ll assume the writer was an ordinary human who used his own experience to fill in details of his story; we’ll also assume that a bird noted was a bird familiar to the writer, and was then extant in the general region of the Middle East. In that region two dove or pigeon species predominate: the Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), also known as park pigeon, homing pigeon, or carrier pigeon, and the European (or Common) Turtle-Dove (Streptopelia turtur). Biblical Hebrew uses two words for these two species: tor (תֹּר), translated as dove or turtledove, and yonah (יוֹנִים), usually translated as pigeon, but sometimes as dove. Occasionally these words occur together, as when Leviticus 5:7 suggests using “two turtle doves or two young pigeons” as sin-offerings. Our cited passage states yonah, so Noah’s “dove” could be of either species.

European Turtle-Dove (Wikipedia)

Of the seventeen species in the Streptopelia genus, the European Turtle-Dove is the most widespread and common, found from the Azores Islands in the west, across northern Africa, Europe, the Mid-East and western Asia to Iran and far-western China. They are widely domesticated by humans, used as food and as caged companions. The “turtle” part of their name – as may also the Hebrew “tor” – refers to their cooing call, which sounds to human ears like the word “turtle.” This widespread impression is recognized in their name in many languages: French – Tourterelle des bois, Dutch – Tortelduif, German – Turteltaube, Swedish – Turturduva, and in the scientific species name, turtur. However, many people refer to this much-admired bird as simply “Turtle“, as did the British when the King James version of the bible was published in 1611. In recent years, and in regions which do not host turtle-doves, bible readers are often mystified by the following passage:

“For lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land…” Song of Solomon 2:11-12 King James Version

Since when does one ever hear a turtle say anything? One doesn’t, and recent translations and updated versions have re-translated the Hebrew tor in this passage from “turtle” to “turtle-dove.”

Why send out a Dove? All pigeons and doves build nests of twigs. Not very well, I should add. They may be so loosely constructed that one can see the eggs through the bottom of the nest. After a mated pair locate a suitable nest site, frequently a fork in a tree limb, they (sometimes only one) fly off to find twigs to bring back; these may be dead and broken, but living twigs may be preferred for their flexibility. One of the pair may stay to guard the site and suitably arrange twigs brought by the other until the nest is complete. All pigeons and doves are strong and swift flyers, able to quickly cover a lot of area without needing to land. Many species can also find their way home through vast featureless areas.

Rock Pigeon at Malibu Lagoon

(Jim Kenney 2-19-10)

The Rock Pigeon, whom the Israelites called yonah, has been domesticated for millennia for food, feathers, fun, and not least for its ability to reliably carry messages to its home roost from any distance or direction, despite adverse conditions of weather and light. Historians report that the use of “carrier pigeons” probably began in ancient Persia, and dates to at least 1000 BCE. Phoenician merchants at sea used the pigeon post to send messages home; the Greeks used them to announce results of the Olympic games. Such an instinctive “homing” pigeon, one who seeks and gathers twigs with which to build its nest, would be the perfect animal to recruit for the task of finding and returning living vegetable matter, to indicate the end of a flood and the reemergence of land and vegetation. It could fly for hours, cover a huge area, and reliably return, bringing a live twig if it could find one, or a dead twig if that’s all it could find. Genesis says (in translation) that Noah sent out a “dove,” but in all likelihood, it was not the European Turtle-Dove but the Rock Pigeon, whose biblical Hebrew name yonah, used in this passage, is translated as either pigeon or dove.

Rock Pigeons on cliff in Israel (Igor Svobodin)

The Rock Pigeon nests on barren cliffs, often in arid, confusingly-configured regions, and often had to travel wide and far to find food, water, and nesting material. This constellation of characteristics suggests that they may be the reason the species evolved such a remarkable homing ability.

The selection of the Rock Pigeon for this role in this story demonstrates that the writer was aware of four things: First, the mere fact of this species’ existence; Second, the bird’s ability to fly fast and far; Third, its natural desire to seek and

Peace dove with Olive Branch (Google)

bring back twigs for the purpose of nest-building; Fourth, its remarkable ability to recall the location of its home roost in the vastness of an unfamiliar and potentially featureless region. The earliest use of the Rock Pigeon as “carrier” pigeon is probably unrecorded, but here we see a suggestion that it was known, at the time of this story, in the Middle East. Because of this biblical passage, doves are now symbols of peace (or the forgiveness of an angry deity) and the olive branch is a symbolic peace-offering.

Linguistic confusion between pigeon and dove remains common today. There is no set rule as to which is which. Typically, larger birds are pigeons, smaller birds are doves. Each of the 45 genera in Columbiformes – with one exception – consists (in English) entirely of pigeons or entirely of doves, never a mixture. The sole exception is the genus Columba (which includes our Rock Pigeon) comprising 36 species, of which three are called “dove,” the rest are “pigeons.” The continuing drive for English avian nomenclatural consistency, including the goal of calling all species in the Columba genus by the name of “pigeon” brought, in 2003, the change from Rock Dove to Rock Pigeon. By it’s size it should be called a pigeon. All it’s closest relatives are called pigeons. The bible (except Noah) calls it a pigeon, park statues everywhere call it a pigeon, messenger services call it a pigeon. But speakers of English long branded it a dove, and, in biblical translation ever since, it has remained a dove.

Carrier Pigeon carries a canary (WeirdUniverse)

The native range of Rock Pigeon is obscured by domestication. For millennia they have accompanied humans, and the descendants of escaped and released birds number into the many millions, if not billions, world-wide. They do not migrate. Their original range probably extended from the mountains of Morocco in the west to the eastern Indian Himalayas. They nest on ledges and in holes of rocky cliffs, hence the name Rock Pigeon. They have survived and spread exceedingly well throughout the modern world because humans have considerately constructed ledge-filled artificial cliffs for them, which we call buildings and bridges, and freely fed them sumptuous feasts, which we call trash.

Rock Pigeons relaxing on man-made cliffs (Chuck Bragg 9-25-11)

Incidentally, Genesis 8:12 misrepresents this faithful and vigorous bird when saying it did not return to the ark. Very little will keep a Rock Pigeon from returning to its home roost. They do not often become lost. Only accidents, predation, or (unlikely) a new mate would keep it away from its home, its nest, and its mate. As all animals except our pigeon (or dove) were supposedly still parked on the ark at this time, there would be no predators or potential mates to keep it away. The disappearance of our pigeon is almost certainly a metaphor, a case of the biblical writer taking literary license to send a signal to the alert reader. After its scouring, the damp, new earth has received our pigeon – and all her living creatures by extension, including wayward humans – back into her fruitful arms.

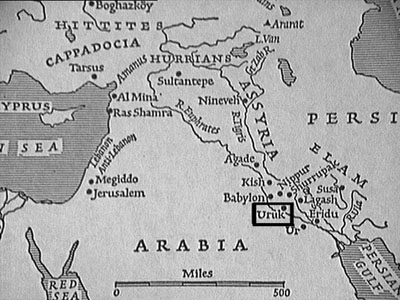

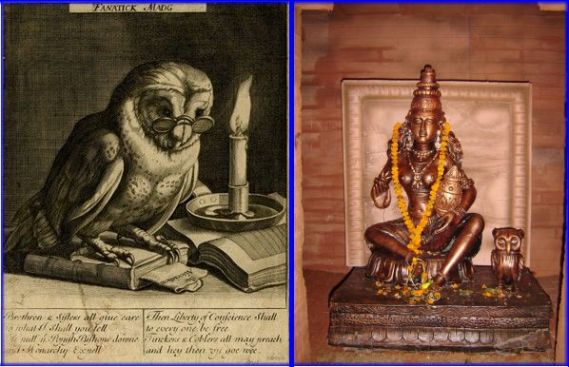

Bible Factoid #1: Noah, the Flood, and the Epic of Gilgamesh

The biblical story of Noah and the flood is greatly predated by the flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh. First discovered in Nineveh in 1853 and translated in 1870, the epic – considered by many scholars to be the first written work of literature in the world – dates to about 2100 BCE and relates the adventures of Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk in southeastern Mesopotamia. It was a popular story of that age

Mesopotamia & location of Uruk, city of Gilgamesh (nkerns.com)

and region, and parts of it have been found in excavations of other ancient cities. The description of the flood occurs near the epic’s end when Gilgamesh travels far to the northwest to find Utnapishtim, the then-immortal survivor of an ancient

Deluge Tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic in Akkadian script (Wikipedia)

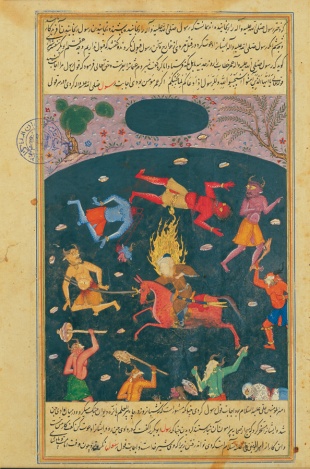

flood. In Utnapishtim’s narration, the rains lasted six days and nights; the boat then grounded on Mt. Nisir, a hatch was opened and the mountain could be seen; the boat rested for 6 days and nights; Utnapishtim then released a dove, which returned; a sparrow was released which also returned; a raven was released which found food, flew around and did not return. Utnapishtim then left the boat and made a sacrifice on the mountaintop. It is illuminating to compare these details to those found in Genesis 6-9.

This Gilgamesh story is now near-universally accepted by biblical scholars as the origin of the flood story found in Genesis. Before its complete translation in 1870, no one knew that the story of Noah’s flood was not original with Genesis, but was based on a far earlier story. [Chuck Almdale]

Additional Sources:

1. The Epic of Gilgamesh, translation and introduction by N.K. Sandars, 1964, Penguin Books, Baltimore. Pgs 7-16, 105-110.

2. New English Bible with the Apocrypha, The, Oxford Study Edition. Sandmel, Samuel, Suggs, M. Jack, Tkacik, Arnold J.; eds. (1972) Oxford University Press, New York

Return To Top

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study II:

Sandgrouse or Quail?

This week’s topic comes from Exodus and Numbers, books two and four of the Pentateuch, when the Israelites, fearing starvation in the barren Sinai desert wastes, pine for the “fleshpots of Egypt,” and Yahweh promises to bring them manna and flesh to eat. [I’ll use Yahweh**, the commonly accepted name for the deity, as it’s the closest transliteration of the Hebrew YHVH, spelled without vowels (in English left-to-right sequence), written in these passages.]

Climbing Mt. Sinai (Rough Guides)

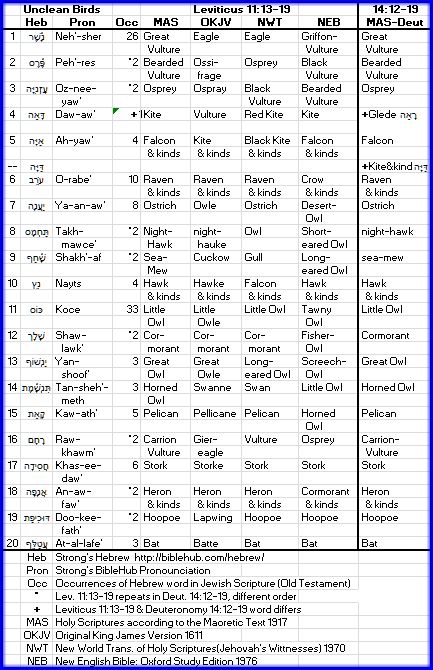

The Lord [יְהוָ֖ה – Yahweh] spoke to Moses and said: “I have heard the complaints of the Israelites. Say to them, “Between dusk and dark you will have flesh to eat and in the morning bread in plenty.”.…That evening a flock of quails (שְׂלָו – selav) flew in and settled all over the camp…

Exod. 16.11-13 New English Bible

Then a wind from the Lord sprang up; it drove quails (שְׂלָו – selav) in from the west, and they were flying all round the camp for the distance of a day’s journey, three feet above the ground. The people were busy gathering quails all that day, all night, and all next day, and even the man who got least gathered ten homers. [10 homers = 890 gallons!] They spread them out to dry all about the camp. But the meat was scarcely between their teeth, and they had not so much as bitten it, when the Lord’s anger broke out against the people and he struck them with a deadly plague. Num. 11.31-33 New English Bible

Cartoon by Jeff Larson

The careful reader of these two passages, with their surrounding passages, will notice that in Exodus the quail and manna are simply sustenance as promised by Yahweh, whereas in Numbers, the quail are a punishment for the Israelite’s complaints about having only manna to eat; many of the people sicken and die from eating the quail. I’ll set aside this inconsistency for now and address our primary birder’s issues: what kind of birds are these, where did they come from, and what are they doing in the Sinai desert? Are numbers as enormous as described possible?

Sinai Peninsula satellite view from southeast (New World Encyclopedia)

Descriptions of birds given by non-birders are notoriously insufficient and inaccurate, as are what they think is the bird’s name. What birder has not been asked to identify a bird based on a verbal description which fits either hundreds of species (“It was dark and small…”), or no species at all? (“…with long legs and a green crest.”) One learns to be skeptical and to closely question in order to gather useful information. When I first read the above passages, the sandgrouse came immediately to mind. It’s not a quail, but an inexperienced, unconcerned or naked-eye observer might think it a quail, and binoculars were certainly lacking in the ancient Middle East.

Crowned Sandgrouse soaking their breast feathers

(HotspotBirding.com)

Sandgrouse are an interesting family of sixteen species, grouped into two genera. [Video] They are currently classified in their own order, Pterocliformes (notable wing), but they were previously placed in the order of Pigeons (Columbiformes) to whom they are remarkably similar. Sandgrouse habitats are typically described as “inhospitable,” “barren,” or “sere,” and includes wastes, plains, savanna and thorn scrub from western and southern Africa to India and Manchuria. [In a hot and unbelievably barren waste in South Africa, I once nearly stepped on a beautifully camouflaged sandgrouse, whom I did not see until it flushed from its nest and eggs, a foot from my feet.] Because they typically nest far from any water, they must swiftly fly (60 mph is common) long distances for water and carry it back to their nestlings. A unique adaptation enables them to do this: breast feathers which absorb water like a sponge and retain it well enough to allow their returning it to their young, who lap the moisture from their breast.

Birders know the most certain way to spot sandgrouse is to hide by a desert waterhole. Sandgrouse, usually in groups, visit waterholes in the morning and especially in the evening, first drinking, then wading into water to saturate their breast feathers, then flying back home. It seems that sandgrouse might be the answer to our question: they resemble a grouse (or quail), they live only in desert-like habitats, and they invariably come to waterholes in the evening.

Crowned Sandgrouse flock at pool in Israel (Eyal Bartov)

There are three species currently living in the Sinai desert and adjacent regions: Spotted (Pterocles senegallus), Black-bellied (P. orientalis), and Crowned (P. coronatus); the Pin-tailed (P. alchata) Sandgrouse lives nearby in Arabia and Mesopotamia.

However, one problem remains. Because they are non-migratory permanent residents in their respective ranges (except for altitudinal migration of the Tibetan Sandgrouse), sandgrouse don’t congregate in large flocks as do many birds during migration, and their arid, barren homes can not support large resident concentrations of them. Perhaps sandgrouse is not the bird after all.

The Common Quail, Coturnix coturnix, (also called European or Eurasian Quail) has been very well-known for a very long time in the old world. Egyptian hieroglyphics from 5000 BC picture them. Their northern breeding range runs from western Morocco, throughout Europe to the Baltic States, across Russia and the Middle East to Lake Baikal and India. The western Eurasian breeders winter in Egypt and down the Nile River to Sub-Saharan Africa, while central Asian breeders winter in India. Some far-western birds migrate past Gibraltar, but most avoid that enormous barrier to European avian migration, the Mediterranean Sea, by flying around the east end: through Egypt, the Sinai, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and onward to Europe and western Asia. Northbound flocks can be in the hundreds; southbound groups are usually much smaller.

Common or European Quail (Ján Svetlík)

All other quail species are non-migratory residents and are poor flyers: fast and noisy on take-off but not adapted for sustained flight, and typically fly short and low. The Common Quail, adapted to migration, is longer-winged than other quail, and while able to fly swiftly, they also fly quite low, often nearly hugging the ground. Even today, many thousands of them are netted annually during migration in Sinai and other parts of Egypt; such annual netting used to number into the millions, but the population became dangerously reduced during 1970-1990.

Sinai net-hunting is like that elsewhere in Europe; nets are strung along valleys and mountain ridges where birds fly very close to the ground to conserve energy. It’s near-certain that for as long as humans have lived in this area, migrating Common Quail have provided a tasty and bountiful springtime repast. Flying, for quail, is thirsty work, and they try to find water before night falls, when they either go to roost or continue their migration in the dark. The mirror-like shine of desert water pools, visible for miles during daylight, become invisible ink blots at night, so stopping near sundown is best. Common Quail can and do migrate during the day and/or at night, but they also need to periodically stop, rest, drink and eat.

Common Quail netted at ground level in Gaza (Middle East Eye) [1]

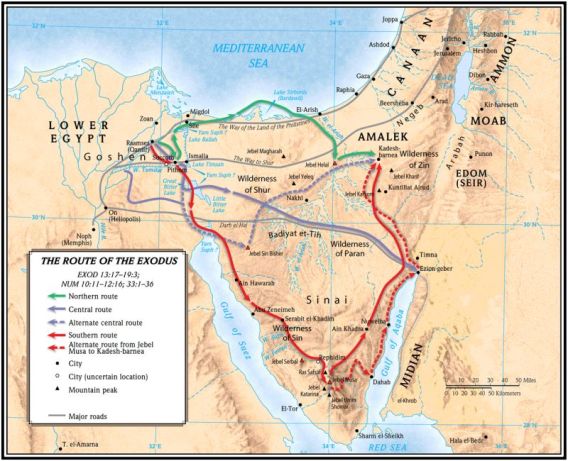

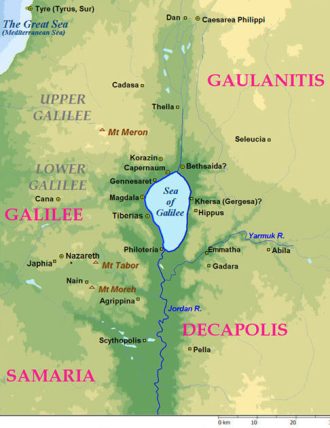

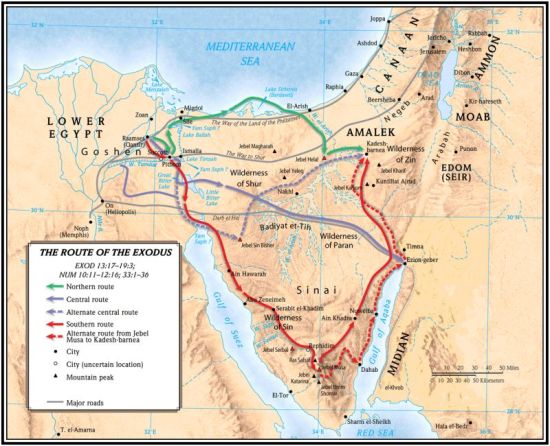

The solid red line (on this map) denotes their route from Egypt to Mount Sinai as presented in the Torah. According to the Torah, Mount Sinai can only be located at Jebel Musa, its traditionally accepted location. (All Faith.com)

Poisoned Quail?

The passage in Numbers 11.31-33 says that large numbers of people died almost immediately after eating the quail as a punishment for their greed. I can think of four possibilities to explain this. First, people who have not eaten meat for a long time can have a bad reaction to it. Second, sun-dried quail flesh may not be free of contamination. Third, birds, like people, can build up high levels of metabolites in their muscles during periods of sustained exertion. (Lactic acid buildup during anaerobic exercise creates that “burn” in your muscles.) Perhaps such metabolites could poison hungry, involuntary vegetarians who greedily gobble down their food (possibly sun-dried or insufficiently cooked). Fourth, many people today believe that quail migrating around the east end of the Mediterranean can accumulate toxins by eating hemlock or other poisonous plants. The term coternism (from Coturnix for “quail”) describes those who have been poisoned from eating quail. Aristotle, Philo, Galen and other ancients commented on such quail poisoning.

It has been reported that Common Quail are poisonous only during migration, and only those that fly around the eastern end of the Mediterranean; not those following other routes or while on their breeding or wintering grounds. Various food plants have been blamed: hellbore, henbane, hemlock, woundwart. Whatever the toxin, it appears to be stable, as cases have been reported of people poisoned by four-month-old pickled quail, and by potatoes fried in quail fat. Some quail eaters practicing such “dietary roulette” needed to have their stomachs pumped.

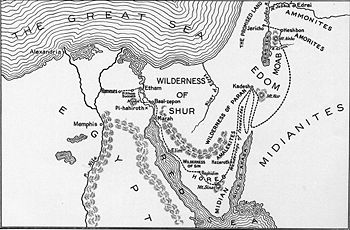

Probable Midian territories during Exodus era

(New World Encyclopedia)

In Exodus 2-4, Moses is described as fleeing Egypt to live for years in the “land of Midian,”, where he married Zipporah, the daughter of Jethro, a Midian priest, and spent time minding Jethro’s flocks of sheep, a task which took him into the wilderness, including the vicinity of Mt. Horeb. Such an occupation would quickly teach anyone how to find water and food both for himself and his sheep, and Moses would have become quite familiar with local water holes and the periodic passage of flocks of quail, knowledge that would come in handy if one found themselves leading a crowd of foreigners through this region. An experienced leader might plan ahead and specifically choose quail-migration-season as the preferred time to escort travelers.

As usual, biblical scholars cannot agree on the location of “Midian,” “Mt. Horeb,” “Mt. Sinai,” whether Mt. Horeb is also Mt. Sinai or not, or if the mountain has two peaks – one called Sinai, the other Horeb – the route of the Exodus, the number of people, the length of time, and just about every other detail in this entire story.

But whether these events in Exodus and Numbers actually occurred as described is, frankly, irrelevant for the purposes of this essay. We’re simply looking at what birds are mentioned, and what was written about them. The facts pertaining to Common Quail behavior as described in these passages (exaggerations excepted), actually did, and still do, occur. The events could have happened to anyone traveling through the Sinai Peninsula during quail migration season(s), and the mere fact that the description was written down in Exodus (whenever and by whomever it was written), means that they had previously occurred to some people, and were probably common knowledge to local residents. Such local knowledge concerning water and food would be essential to merchants, caravan leaders, shepherds, and anyone else traveling through such a difficult and barren region.

** Bible Factoid #2: YHVH [יְהוָ֖ה] [Yahweh]: When Moses asks – in Exodus 3:13-14 – the deity for his name so he can tell the Israelites who is sending him, YHVH (letters = yod-he-waw-he) is the answer. This is usually translated as “I AM.” The longer passage is “YHVH [I AM]; that is who I am. Tell them that I AM has sent you to them.” The Hebrew form YHVH is actually third person – “He is” – but as the deity is depicted as explaining his own name in the first person, the explanation becomes “I am.” [New English Bible, footnote Ex. 3:12] This explanation is expanded in Ex. 3:14-15 to “I will be what I will be.” Since this was written, scholars and theologians have argued long and hard about this name, its meaning(s) and implications. It should be noted that “I AM” – in numerous languages – is widely used in Hindu and Buddhist religions as a mantra and an object of meditation; many consider it to be the briefest, truest expression of the mystical presence of the deity – or nirvana – within each human consciousness. As such, it is also being examined in the recently developing field of Neurotheology.

Note: The link to an article on Grouse netting in Gaza is placed below, rather than embedded in the text, because I decided to not leave our website permanently linked to that site. [Chuck Almdale]

[1] middleeasteye . net/in-depth/features/common-quail-feeds-poor-gaza-594657522

Additional Sources:

1. Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 4. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1997) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Pg 55.

2. HBW Vol. 2. (1994) Pg. 509

3. New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition (NEB), Sandmel, Samuel General Editor, (1976) Oxford University Press, New York.

4. Birds of Europe. Mullarney, K., Svensson, L., Zetterström, D., Grant, P.J. (1999) Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Return To Top

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study III:

Junglefowl in Judea?

Flood-pigeons, desert-quail – what could be next? Our topic this week is arguably the second most famous bird in the bible, following the pigeon and his Noah. We speak, of course, of the chicken, or more specifically, the male of the species, the cock.

Cock Red Junglefowl in all his glory, Corbett Nat. Park. northeast India (Rahul Pratti)

Peter replied, ‘Everyone else may fall away on your account, but I never will.’ Jesus said to him, ‘I tell you, tonight before the cock crows you will disown me three times.’ Matt. 26:33-34 New English Bible

Methinks the man doth protest too much. (Tatcog School)

Shortly afterwards the bystanders came up and said to Peter, ‘Surely you are another of them; your accent gives you away!’ At this he broke into curses and declared with an oath: ‘I do not know the man.’ At that moment a cock (ἀλέκτωρ – alektor) crew; and Peter remembered how Jesus had said, ‘Before the cock crows you will disown me three times.’ He went outside, and wept bitterly. Matt. 26.73-75 New English Bible

The third time is the charm, as they say. All Christians ought to know of this story, as will many non-Christians. Who cannot feel both pity for poor Simon “Peter” (Πέτρος – Petros: Greek** for rock), and embarrassed empathy with him in his cowardice and fear. How many of us would be courageous and foolish enough to declare faith and allegiance to Jesus, when he’d just been hauled off, probably to be executed, along with any followers who didn’t slip away.

Peter, the rooster and Jesus; Copy of painting by Carl Heinrich Bloch 1834-90 (RonCarol205)

The story tells us that Jesus – well aware of Simon’s rash and boastful tendencies – told him that despite his protestations of faithfulness unto death, Simon wouldn’t even make it until the next dawn before “chickening out” three times. Yet, Jesus forgives Simon his weakness in advance.

This is one of the few tales found in all four Gospels. After the troops arrest Jesus, Simon follows them to see what will happen. Perhaps he will rescue Jesus! In three versions, Simon is alone; in John 18:15 he is accompanied by another disciple. He (or they), end up at the High Priest’s house, where he mingled with others in the courtyard around a fire, trying to stay warm, (see picture above) yet still keep a low profile. But his northerner’s accent gave him away as one of the Galilean followers of Jesus.

Mark 14:72 has the cock crowing twice; the other three passages agree on once. But we’ll now leave Simon and Jesus to follow our own trail, which is to examine the third actor in this play, that crowing rooster, and see how he got to first century Judea and why he was crowing.

Anyone who has ever slept near a farmyard, anywhere around the world, knows that roosters (or cocks, as the male of the chicken and allied species are called, as in Peacock), call at dawn, waking us up whether we want to or not. Actually, nearly all birds with any kind of voice and who maintain personal territories, call around dawn during their breeding season, largely to let their avian neighbors know that they lived through the night and they’d better stay out of his territory. Most aren’t as loud as the rooster, for whom it seems to be always breeding season.

Travelers to the tropics are often enchanted by the rainforest “dawn chorus’. Birds begin murmuring their nearly inaudible ‘whisper songs’ around first light, as if still groggy, get really loud around dawn, and dwindle away by ½ – 1 hour after dawn, when it’s light enough for them to begin finding their first meal of the day. In fact this happens everywhere; but it’s more noticeable when 500 species of birds sing within a mile of your bed. Cocks are no exception; his territory may consist of only a few bare square feet of ground, but it’s his and he will fight to the death to protect it and his mating rights with any hens therein. In Muslim countries, cocks first crow at first light, when the Muezzin first calls the faithful to prayer, when the still-unseen sun tints, however slightly, the eastern sky.

About one-third of the 174 members of the Phasianidae (Pheasant & Partridge family) are non-monogamous, including the Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus), the official English name for our chicken species. Red Junglefowl are very sexually dimorphic, and the male has larger tail and fleshy comb, with overall brighter and more colorful plumage. The male maintains his territory by crowing and fighting with male intruders, using his bony spurs as weapons, and he gathers as many females as he can. Crowing, especially at dawn, is essential to his survival, to fulfill his evolutionary imperative to get his genes into the next generation as often and as successfully as possible. Within his territory, the rooster “rules the roost.”

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English name “cock” for the male chicken is from “kokke” in Old English, “coq” in 12th century French, and kokkr in Old Norse. All these names are likely echoic, imitative of its voice, as in “cock-a-doodle-doo.” The name “rooster” comes from “one who roosts;” both males and females of many Phasianidae species spend the night safely roosting on tree limbs.

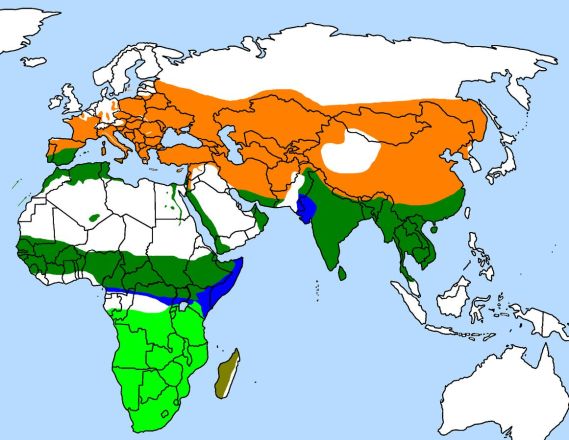

Home range of Red Junglefowl

(Handbook of Birds of the World)

All domesticated animals originated somewhere; they haven’t always lived in our backyards. Cattle originated in Europe, where wild cattle are long extinct; Ring-necked Pheasants ranged from western Georgia, east of the Black Sea, to east China; Guinea Pigs began in Peru, where they were a favorite food of the Incas. Red Junglefowl originated in Southeast Asia, where they still range from Nepal and central India eastward through Burma, Vietnam, and Malaysia to the Indonesian Lesser Sunda Islands. Their traditional range likely stopped at Bali, just west of the Wallace Line dividing Asian fauna from Austronesian fauna, but they now live throughout Sulawesi and the Philippines

Wallace Line – Bali is eastern end of Red Junglefowl range, excluding introductions by humans. (Wikimedia)

where they were introduced millennia ago. Their official English name, Red Junglefowl, comes from their original color and preferred habitat. Even now, they regally stalk silently through the forest undergrowth, scratching the soil for seeds, grubs, and grit, leading their precocial chicks on their daily search for food. It is a wonderful thing to hear the dawn territorial call of a cock Red Junglefowl in the dripping ink-black rainforest of Malaysia, and know that this bird has escaped the doom befallen so many of his brethren. It’s even more wonderful to see them; both sexes are beautiful, magnificently plumaged birds. This pair, at least, will never suffer that most humiliating of all fates, to become a McNugget.

According to recent genetic studies, the clade of Red Junglefowl living at the western end of their range, in India, are the ancestors of all domestic chickens now found throughout the New World, Europe and the Middle East.

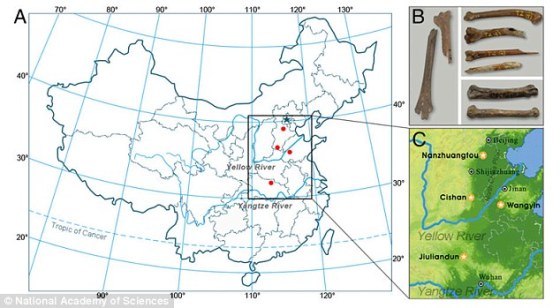

Location of chicken fossils, Yellow River area, China (Daily Mail)

In northern China, fossilized Chicken bones dating back 10,500 years were recently discovered in the Yellow River area, which DNA analysis determined to be Gallus gallus. This area is well outside the known historical range of the species and they are likely the oldest examples of domesticated chickens in the world. It is thought that the ancestors of this group were from southeast Asia – Vietnam for example – rather than from the Indian clade.

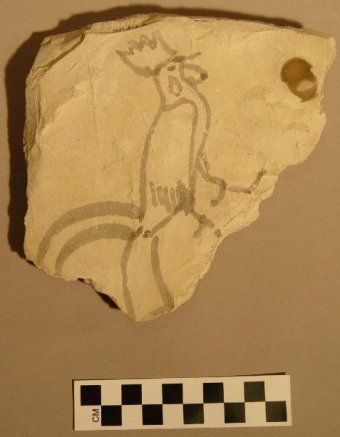

Ostracon of rooster c.1500 BCE, discovered by Howard Carter, 1923, while searching for King Tut’s tomb. (British Museum)

An ostracon (inscription on potsherd) from fifteenth century BCE Egypt depicts a cock. The Annals of Thutmose III (1558-1538 BCE), describing his battles in Babylonia, mentions bringing back to Egypt the “bird that gives birth every day.” By the fifth century BCE they appeared in Lydia (Western Turkey) and Greece.

A Greek legend tells us that western civilization was saved by chickens! In 480 BCE, Athenian general Themistocles, leading his troops to fight Persian invaders stopped to watch two cocks fighting by the side of the road. He gathered his men to watch and said, “Behold, these do not fight for their household gods, for the monuments of their ancestors, for glory, for liberty or the safety of their children, but only because one will not give way to the other.” The soldiers took heart from this – perhaps they didn’t want to seem less courageous than chickens – and marched on to defeat the Persians, thereby saving Athens, Greece, Democracy and Western Civilization. Score one for the chickens, the very models of bravery.

Nowadays, chickens are found by the billions wherever humans live. We are surrounded by these fowl in so-called egg or chicken “factories,” living lives that make our lives of quiet desperation (as Thoreau said) seem in comparison like ecstasy in paradise. We have thoroughly, remorselessly, and unremittingly domesticated them, but it wasn’t always so.

Chickens then, as now, were common trade goods between peoples. These useful and easily maintained animals produce eggs, feathers and flesh; they’re great predators of annoying pests in your garden; the males, equipped with sharp spurs on the back of their feet, are the central attraction of one of the world’s oldest blood “sports” and gambling attractions. Such an animal would spread rapidly among all people who encountered them. Evidence suggests that the residents of Harappa in the Indus Valley not only had chickens, but they traded with the Middle East. Directly or indirectly, chickens were traded hand to hand, village to village, tribe to tribe, nation to nation, until they made their way to Persia, Syria, Egypt, Lydia, Greece and Judea, where they were common as dirt long before the birth of Jesus. Jesus and Simon may have walked from the Galilee to Jerusalem, but that rooster and his ancestors came a whole lot farther. They were so common in Judea that they were hardly worth mentioning, and wouldn’t have been, if first century Jews couldn’t reliably count on them as heralds of the coming dawn, when the new sun shines upon us all.

Rooster on top of First Presbyterian Church, Wilmington, NC (MyReporter)

There is one – and only one – additional mention of chickens in the entire bible.

“O, Jerusalem, Jerusalem the city that murders the prophets and stones the messengers sent to her! How often have I longed to gather your children, as a hen (ὄρνις – ornis) gathers her brood under her wings, but you would not let me.” Matthew 23:37

Had this image caught on, rather than that of the good shepherd with his lambs, it might have completely changed the course of Christian iconography. Imagine, if you can, Jesus as the “Hen of God,” and all people as his chicks.

But chickens weren’t completely overlooked by the new religion. Pope Nicholas I (858-867 CE) decreed that a figure of a rooster should be placed atop every church as a reminder of our story—which is why many churches still have rooster-shaped weather vanes.

Red Junglefowl pair in forest, where they belong.

(DiscoverLife – Tom Stephenson)

I’ll leave you with one final thought. People today often assume that commerce of goods and ideas between the Orient and the Occident was nearly nonexistent in ancient days. But we now see that chickens, tangible, living animals subject to loss, escape and death, were transported by humans through forests, deserts and rugged mountains, at least 2500 miles by land, well before the time of Jesus. What about intangible things? Our so-called “Arabic numerals” originated in India, where Persians discovered them and popularized them in the Middle East around 825 CE. We know that chickens preceded Arabic numerals by 2300 years. Might not ideas, ethics, philosophies, religious values and theological tenets have made their way back and forth even more easily? Perhaps the origins of the religions and philosophies of the Mediterranean and Middle East – the philosophy of Greece, the polytheism of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, the monotheism of Jews, Christians and Muslims – are not so local and insular as they appear on first glance.

For much more on the history of Red Junglefowl: Smithsonian – How the Chicken Conquered the World

And…just to shake the ground beneath our feet, here’s another view which posits that the cock in our story was not a bird at all, but a horn!

**Bible Factoid #3 – New Testament Greek

You may have noticed that we are now translating from Greek, not Hebrew. The New Testament was written in Greek – not Hebrew, Aramaic, Latin and definitely not the English of the King James Version (1611). The language was not classical Greek, but Koine (street, common or vulgar) Greek. Koine, also called Hellenistic Greek, developed from the various classical Greek dialects and was the main spoken form from the time of Alexander the Great (died 323 BCE) until about the time of Tiberius II Constantine, circa 580 CE. New Testament Koine Greek was filled with local semiticisms, not used elsewhere in the Greek-speaking world. [Imagine if the King James Version had been written in modern Jamaican patois rather than Elizabethan English.]

After Alexander’s conquest, the Middle East was ruled by Greeks (Hellenistic Period) until the Romans conquered the Middle-Eastern empire of the Seleucids in 63 BCE. Greek was the dominant cultural language, so much so that the Jewish Scriptures (the Christian Old Testament) were translated from the original Hebrew into Koine Greek, beginning in the third century BCE and finished in 132 BCE. This translation, called the Septuagint (frequently abbreviated LXX) for the 70 (or 72) scholars reportedly involved in the translation, is believed to have been commissioned by Egyptian King Ptolemy II Philadelphus and intended for the Library at Alexandria. In 1st century CE Judea, Hebrew was still spoken alongside Greek and Aramaic. Aramaic was dominant in Galilee and was probably spoken by Jesus and his followers. A few of the words of Jesus quoted in the Gospels are in Aramaic – abba (familiar form of father – “papa”) and ephphatha (“be opened”) for example. [Chuck Almdale]

References not linked above

Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 2. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1994) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Pgs 452, 529-30.

New English Bible with the Apocrypha, The, Oxford Study Edition. Sandmel, Samuel, Suggs, M. Jack, Tkacik, Arnold J.; eds. (1972) Oxford University Press, New York

Oxford Companion to the Bible. Metzger, Bruce M. & Coogan, Michael D. eds. (1993) Oxford University Press, New York.

Additional Reading

How the Chicken Conquered the World. Adler, Jerry & Lawler, Andrew. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2012.

Return To Top

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study IV:

Birds that Sow, Reap and Store

This week’s topic is not a particular bird, but stems from a general comment about birds. This well-known and oft-quoted verse appears near the end of Jesus’ sermon on the mount, a long oration in which he offers the mass of listeners advice for living a better life.

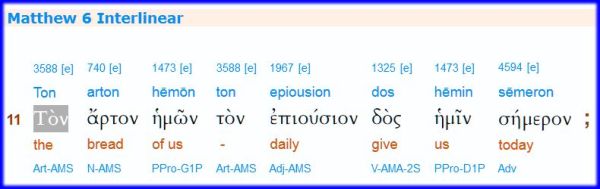

‘Therefore I bid you put away anxious thoughts about food and drink to keep you alive, and clothes to cover your body. Surely life is more than food, the body more than clothes. Look at the birds (πετεινὰ – peteina, plural of bird) of the air; they do not sow and reap and store in barns, yet your heavenly Father feeds them. You are worth more than the birds! Is there a man of you who by anxious thought can add a foot to his height?’

Matt. 6:25-27 New English Bible

Stained glass of Jesus, birds and foxes

(Glass Angel)

Put into a modern context, we are being told that if we let go of our never-ending fears, we’ll fuss and fret less and be happier. Endless anxiety does not make us taller or live longer. Birds do fine without such needless fretting. We are greater than they; we can live better that we do.

The bible is full of poetic and literary devices: similes, metaphors, rhyme schemes, and repetition for emphasis are only a few. However, there are many people who interpret literally passages such as the above and who, knowing little about birds or other animals, might think they actually lead lives of perpetual ease and frolic. As with humans, birds have their own agendas; entertaining humans is very low on their list. Their lives are filled with peril; they need all their courage, wits, and a lot of luck to survive long enough to raise young of their own. 80-90% of all birds die in their first year.

To illustrate some of the survival strategies birds use, I’ve selected three species which anyone in Southern California can see without much difficulty.

Clark’s Nutcracker, Aspendell, Inyo Co, CA (Joyce Waterman)

High in the mountains of western America, including our local San Gabriel Mountains, lives the Clark’s Nutcracker. Discovered by William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition near the north fork of the Salmon River (near modern-day Kamiah, Idaho) on August 22, 1805, they were later named for him.

Eurasian Nutcracker, Manzushir Khiid, Mongolia

(Dreaming of Danzan Ravjaa, January 2009)

The family Corvidae (Crows and allies) has 125 species, grouped into 25 genera. The three nutcracker species are in the Nucifraga genus: Eurasian (previously Spotted) N. caryocatactes, Kashmir N. multipunctata, and Clark’s N. columbiana. Kashmir Nutcracker is restricted to Pakistan and northwest India;

Kashmir Nutcracker

(painting by John Gould, 1849)

Eurasian ranges widely from central Europe to the eastern Himalayas and far eastern Siberia, getting no closer to Judea than northern Greece; Clark’s ranges across western U.S. and Canada, from northern Baja to British Columbia and down the Rocky Mountains to New Mexico. All three species live on conifer-covered alpine slopes, ranging between 3500 ft. and tree line, usually between 10,000 and 12,000 ft.

A close relative of crows and jays, Clark’s Nutcracker is twelve inches long, a bit larger and stouter than our local California Scrub-Jay. It does not migrate, but remains resident in its alpine coniferous habitat throughout the windy, bitter cold of the mountain winters, occasionally descending to lower slopes. Trees and shrubs provide no food for it at that season, yet it survives, despite winter’s high energy demands. How it does this is quite amazing.

Clark’s Nutcracker pulls a nut (Greg Bergquist, 10-15-04)

The Clark’s Nutcracker survives the winter primarily by eating pine nuts. The nuts, however, are not on the cones which may have blown away in the high velocity winds, but are safely stored in the ground. Like squirrels, nutcrackers spend the autumn extracting pine nuts from cones. Their long, pointed and stout bill is perfect for hammering on cones and plucking out nuts. But they don’t store the nuts in a few large close-at-hand caches like the squirrel. What they do is far more interesting and ecologically beneficial.

The nutcracker packs a mass of seeds into its sublingual (below the tongue) pouch and carries them, as much as ten miles, to its storage area in deep woods or on a windswept ridge. There, where the coming winter’s snow will lie less deep, it makes a hole in the soil with its sharp bill, pushes in one or more seeds, and covers the hole with soil or ground litter. More holes are made for the other seeds. Then it flies back to the ripe-seed ground to repeat the whole process. Individual nutcrackers may store 100,000 seeds in a single season, creating many tens of thousands of holes. And it remembers where the holes are. In natural and experimental situations, nutcrackers have recovered 50 to 99 percent of stored seeds. Experiments show that they remember each hole’s positions relative to local landmarks such as trees and rocks. If such landmarks are moved, say by a meddling scientist, the bird seeks for holes where they ought to be (relative to the moved landmarks) but are no longer.

Clark’s Nutcracker caching nuts, Mt. Baldy, CA (“Bob” – July 2013)

Choosing areas for storage where snow will lie less deep ensures easier retrieval of the seeds. Pine nuts are nutritious, loaded with energy-packed oil, and can sustain the birds through winter. But no nutcracker retrieves all their nuts. Some remain in the ground, sprout, and grow into new trees. Windswept, barren slopes provide young trees with more sunlight and less competition from mature trees. Thus the forest is replenished.

Juvenile Clark’s Nutcracker, Colorado (Joyce Waterman)

Studies have shown that the vast coniferous forests of (pre-European occupied) western North America were created largely through the activities of squirrels, nutcrackers and several of their Jay relatives. Heavy cones and nuts do not travel far without animal transport, and nuts in unopened cones frequently fail to germinate. The trees feed the squirrels and birds, and they in turn enable the forests to spread. In a sense the nutcrackers are “sowing” the forests; this shelter and food is reaped by itself and later generations of nutcrackers.

So, when considering the Clark’s Nutcracker, we must agree that they sow the coniferous forest, reap the nuts and have their own personal “barns” of which they memorize every nook and cranny! Think about that the next time you can’t find your car keys.

An alert female Acorn Woodpecker. Placerita Canyon State Park

(Chuck Bragg 4-7-12)

The Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) ranges from southern Washington State down to the western slope of the Colombian Andes Mountains. Except for the southern populations in Central and South America, they have the unusual behavior of collecting tens of thousands of acorns and storing them in granary trees. The granary is not a large cavity containing many nuts, instead it is one – sometimes more – entire tree with tens of thousands of small holes drilled by the woodpeckers into the trunk and large limbs. Each hole takes one-third to one

Acorn Caps. Malibu Creek State Park

(Chuck Almdale 4-12-14)

woodpecker-hours to drill, and into each hole one acorn, still in its shell, is pounded. The woodpeckers gather the acorns in the fall, when they’re ripe, and store them in their granary. Throughout the winter the nuts are extracted, as needed, to feed the colony. The acorns fit tightly and are very difficult for other birds and squirrels to steal them; anyone trying will be discovered and driven off by the granary owners. A granary tree can look like Swiss cheese. Telephone poles have collapsed after years of use as a granary.

Male Acorn Woodpecker with acorn, CA

(Joyce Waterman)

A granary of 50,000 holes will take 15,000 – 50,000 hours to create – far too much time for a single bird or mated pair to create. These are multi-generational projects, begun by a single pair of birds, and continued from one generation to the next. Because acorn shells shrink while stored, they become loose in their holes and must be moved to a new hole, so new holes are constantly added. In order to create and maintain such a huge project, Acorn Woodpeckers developed several unusual breeding strategies, one of which is called helpers-at-the-nest.

Acorn Woodpecker at her granary. Malibu Creek State Park

(Jim Kenney 11-10-12)

Unlike most species of birds, young Acorn Woodpeckers often do not leave their parents to find a mate, build their own nest and start their own families. This species does not migrate to find warmer climes and abundant food in winter. They are resident and stay in their territory throughout the winter. A well-stocked granary enables them to survive the winter but, conversely, it is very difficult for a resident pair to survive the winter without a well-stocked granary. The best way for an Acorn Woodpecker to survive and propagate is to inherit the family granary. So the young of previous years may stick around for many years, helping their parents to feed and protect this year’s crop of nestlings. This enables them to “learn the ropes,”, and be ready to take over the nest holes and granary when the parents eventually die.

Male Acorn Woodpecker at the nest-hole. Solstice Canyon State Park

(Chuck Bragg 5-7-11)

Colonies can begin nesting earlier in the season when they have stored acorns. Studies have shown that colonies with a granary have larger clutches and fledge up to five times more young than colonies or pairs without granaries. Acorn Woodpeckers are great flycatchers, and during the breeding months, the chicks are fed insects, supplemented by fruit and granary acorns. As with humans, inheriting the “family farm” is a tremendous advantage. But not all breeding-age birds can wait that long.

Acorn Woodpecker trio. Malibu Creek State Park, Reagan Ranch section

(Chuck Almdale 4-12-14)

Young female helpers often lay eggs in their mother’s nest. While the dominant female is good at preventing non-family birds from “dumping” eggs into her nest, she is unable to stop her own children from doing so, and cannot pick out and eject eggs not her own. So the helpers have a second reason to hang around. Colonies may even have multiple nest holes and multiple pairs of related birds simultaneously nesting.

Acorn woodpeckers don’t “sow” but they reap and they most definitely store their crop. Their complex and variable breeding strategies have evolved around their dependence on their granaries.

Long-tailed Shrike ready to swoop down on prey. Ambua Lodge, Papua New Guinea highlands (Chuck Almdale, August 2008)

Not all food stored by birds consists of nuts and grain. Shrikes store meat. The Shrike family Laniidae, distributed worldwide excepting Australia and South America, has thirty-two species. All feed primarily with a sit-and-wait method: perch upright on a bare twig or post or wire watching for movement, fly out to capture the prey, bring it back to eat it or store it in the “larder.” Prey can be large insects and small birds, reptiles or mammals, but they are known to kill prey 3-5 times as large as their own body mass. Two examples from Southern Grey Shrike larders: In India, one contained a 10-inch saw-scaled viper; in Israel, another held both a fat Sand Rat and a dead Southern Grey Shrike, an unwary intruder.

Great Grey Shrike and his impaled mouse.

(Aves et ales Animales 6-Mar-2015)

Their larder consists of thorns, sharp twigs or barbed wire, upon which they impale their dead prey; busy shrike may have many corpses thus impaled, for which habit they are also colloquially called “butcher birds.”

Loggerhead Shrike sits-and-waits on his bare twig perch. Malibu Creek State Park

(Jim Kenney 11-20-12)

Our local Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius Ludovicianus) is a 12-inch long passerine, looking much like a Mockingbird but with a thicker, hooked black bill. Lacking the talons of a true raptor, it kills its prey by crushing it in its bill or bashing it to death. They have figured out how to eat poisonous Monarch Butterflies: impale them on a thorn for up to three days until the poison breaks down. Shrikes, endemic to North America, have recently suffered an enormous population decline of 76% between 1966 and 2015, primarily due to eating pesticide-laden prey, it is suspected.

Clark’s Nutcracker, Acorn Woodpecker and Loggerhead Shrike – three local examples of the world’s hundreds, if not thousands, of examples of birds that sow or reap or store their food.

Bible Factoid #4 – Whence Jesus? (Ἰησοῦς –Ihsous)

Since we just finished nitpicking one of Jesus’ sayings, let’s take a look at the name itself. In modern America, many people pronounce it “Geezuz,” which would have been unrecognizable to Jesus’ family and friends. We’ll work backwards to see how it got this way.

The hard “J” that sounds like “G” (as in George) became permanently affixed to “Jesus” in 1611 CE by the King James Version of the bible, by which time the letter “J” had finally entered English. Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, the hard “J” had slowly evolved out of the much softer “IA,” primarily because people thought the hardness sounded more masculine: Iames became James, Ian and Iain became John (except in Scotland), Iestin became Justin, Ieremias became Jeremiah, and Iesus (ee-ay-soos) became Jesus (Gee-sus).

The 1384 CE translation by John Wycliffe from the Latin Vulgate bible into English had retained the earlier Latin “Iesus” (“ee-ay-soos”), which dated back to 382 CE, when Jerome completed the translation of the bible from Koine Greek into common (or “vulgar”) Latin. The Vulgate codified “Iesus” in Latin as the transliteration of Ἰησοῦς (Ihsous, pronounced “ee-ay-soos”) from the Koine Greek of the original New Testament books.

Koine Greek was the written language of the New Testament, but was not the only language spoken in first century Judea – Hebrew, Aramaic and Latin were also spoken; Aramaic was the predominant language around Galilee, whence came Jesus, the man. His Aramaic name was masculinized into New Testament Greek by adding “–s” to the end. [Think of Diogenes, Orestes, Herodotus, Ulysses.] Greek had neither the letter nor the sound of “Y;” “IH” was the closest approximation.

Joshua fittin’ the battle of Jericho, which sat on a major earthquake fault (Noise Curmudgeon)

So the actual name of Jesus the person would have been “Y’shua” (Yod-Shin-Vav-Ayin) Y’-Sh-U-A. This spelling had evolved over centuries from “Yeshua”, which had, by the fifth century BCE, evolved from Yehoshu’a (“Yahweh is salvation” or “Yahweh will deliver”). Thus Y’shua, Yeshua and Yehoshu’a have all come down to us as “Joshua.” The name “Joshua” appears in seven books of the Jewish testament, most notably as the one who “fit the battle of Jericho,” as the song goes.

Jesus = Joshua = Yeshua = Yehoshu’a. But there’s more. Yeshua’s father was Joseph, which through similar changes was transliterated from Aramaic Yôsēp̄ and Hebrew Yossif (יוֹסֵף֙ – Yoseph “he will add”) . In Hebrew “ben” was added to indicate “son of,” as in Ben-Hur (“son of Hur”) or Ben-Gurion; this became “bar” in Aramaic, as in “Bar-Abba[-s]” or “Barabbas” (“son of Abba[-s]” = “son of [informal ] God”) Matt 27-16

We can conclude that Jesus would have answered to the name Yeshua (or Y’shua) Bar-Yôsēp̄, a good Jewish Aramaic name. This brings us to a mystery, to be addressed in next week’s bible factoid. [Chuck Almdale]

Additional Sources:

Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 7. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (2002) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Acorn Woodpecker – Pgs 441-442.

Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 13. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Christie, D.A. eds. (2008) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Shrikes, Loggerhead Shrike – Pgs 744-747, 785-786.

Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 14. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Christie, D.A. eds. (2009) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Nutcrackers, Clark’s Nutcracker – Pgs 611-613.

Birder’s Handbook. Ehrlich, Paul R., Dobkin, David S. & Wheye, Darryl. (1988) Simon & Schuster, New York. Pgs 344, 410, 466.

New English Bible with the Apocrypha, The, Oxford Study Edition. Sandmel, Samuel, Suggs, M. Jack, Tkacik, Arnold J.; eds. (1972) Oxford University Press, New York

Return To Top

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study V:

The Friendly Ravens

Ravens weren’t discussed extensively in the bible – no bird was, for that matter – but they do appear in unexpected locations for interesting reasons. We begin with the citation from Genesis, briefly mentioned in Lesson I.

After forty days Noah opened the trap-door that he had made in the ark, and released a raven (הָֽעֹרֵ֑ב – ha-oreb “a raven” ) to see whether the water had subsided, but the bird continued flying to and fro until the water on the earth had dried up.

Genesis 8:6-7 New English Bible (NEB)

As previously mentioned, that’s all that Genesis says about this raven [עֹרֵ֖ב – oreb], not even whether it ever returned. It probably didn’t, preferring to follow its own agenda rather than Noah’s. Bible Factoid #1 noted that the precursor to this story – found in the much older Epic of Gilgamesh, written circa 2100 BCE – Utnapishtim (the “Noah” of the Gilgamesh) released a raven as the third bird, which found food and flew around and did not return.

Common Raven, Santa Rosa (James Kenney, 11-24-12)

The raven was almost certainly the Common Raven (Corvus corax), the species we find today across North America and Eurasia. Their current range includes all of Europe and Asia Minor, northern Syria and Iraq, and nearly all of the southern and eastern edges of the Mediterranean Sea. Back then, forests in the Near East were more extensive and dense, attractive to our raven. Corvid family members are among the most intelligent and resourceful of birds, and the raven may be the brightest of the bunch, a good choice for any task requiring smarts. So smart, in fact, that they may well decide to skip your task and go do what they want to do. The tale of Noah, perhaps inadvertently, reflects this characteristic.

Hooded Crow on sheep’s head

(Jamie MacArthur, DeviantArt.com)

There are other dark corvids living in the vicinity. Hooded Crow (Corvus corone), about 25% smaller than the raven, is resident from Asia Minor down the Mediterranean eastern shore and the Nile River valley. Jackdaw (Corvus monedula) shares this area, but is largely grey and half the size of the raven. Brown-necked Raven (Corvus ruficollis) is a bird of desert and dry steppes. Their range currently stops south of the Mediterranean southern shore, but includes eastern Israel, Jordan, etc. Their range likely stopped even farther south in biblical times, as it was three millennia closer to the ice age.

Jackdaws, India (Wikia)

Hebrew had only one word עֹרֵב – oreb for raven or crow; bible translators used both at different times, but Common Raven is likely our bird. Incidentally, Hebrew uses positional case-marking on nouns. Notice the progressive increase in Hebrew word length: “raven” עֹרֵב – oreb, “a raven” הָֽעֹרֵ֑ב – ha-oreb, “the ravens” הָעֹרְבִ֣ים – ha-oreb-im, and “and the ravens” וְהָעֹרְבִ֗ים – we-ha-oreb-im.

Brown-necked Raven, Hamada du Draa, Morocco

(Momo, February 2007)

Benjamin the Ravin

Our next citation is actually a red herring.

…Benjamin shall raven (יִטְרָ֔ף – ytrp, “yitrap”) as a wolf: in the morning he shall devour the prey, and at night he shall divide the spoil… Gen. 49:27 1599 Geneva Bible

Many words in the Jewish Hebrew and Christian Greek bibles occur only once*; יִטְרָ֔ף (“ytrp” or “yitrap”) is one of them. Such words usually create arguments because determining their meaning is little more than guesswork. The first KJV edition had “ravin”, later changed to “raven,” creating additional confusion. This obsolete word meant “to take away (goods) by force; to seize or divide as spoil.” Oxford English Dictionary’s last citation in this sense dates from 1625, fourteen years after the KJV was published. Nowadays we say ravening or ravenous. * See list at bottom

“Benjamin is a ravening wolf: in the morning he devours the prey, in the evening he snatches a share of the spoil.” Gen. 49:27 NEB

Inedible Ravens

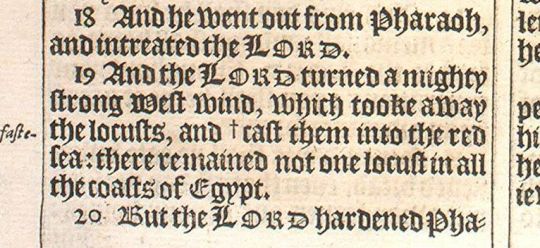

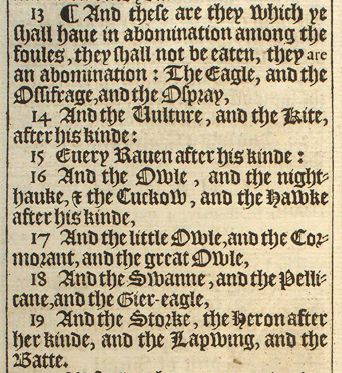

Ravens next appear as members of two equivalent – but not identical – lists of twenty unclean birds.

“These are the birds you shall regard as vermin, and for this reason they shall not be eaten….every kind of crow [or raven] ( עֹרֵ֖ב – oreb )…” Lev 11:13-14 NEB

“These are the birds you may not eat…every kind of crow [or raven] ( עֹרֵ֖ב – oreb)…” Deut 14:12-14 NEB

This list will be covered in a later lesson. Nearly all twenty birds are birds we wouldn’t want to eat today, consumers of dead animals lying on the ground: cormorants, raptors, vultures, gulls. Most – if not all – corvids fall into that category, and the phrase “any kind of raven (or crow)” makes good sense. Four of the forbidden twenty are cited as “every kind of…;” the other sixteen birds are individually named.

The Friendly Ravens

Then the word of the Lord came to him [Elijah the Tishbite]: ‘Leave this place and turn eastwards; and go into hiding in the ravine of Kerith [Cherith] east of the Jordan [River]. You shall drink from the stream, and I have commanded the ravens (הָעֹרְבִ֣ים – haorebim “the ravens”) to feed you there.’ He did as the Lord had told him: he went and stayed in the ravine of Kerith east of the Jordan, and the ravens (וְהָעֹרְבִ֗ים – wehaorebim “and the ravens”) brought him bread and meat morning and evening and he drank from the stream.

1 Kings 17:2-6 NEB

The Prophet Elijah fed by the ravens, Paulwels Frank, 1590 (Alterpersanium.com)

When Israel’s King Ahab didn’t fully appreciate Elijah’s prophesy, Elijah suddenly felt that the deity was telling him to make himself scarce, hide in the wilderness, and live off the land. The “ravens” would help him survive.

As always, commentaries and disagreements abound.

Matthew Henry: God could have sent angels, yet chose lowly ravens because even they would do what he asked.

Barnes: Most ancient versions translate as “ravens;” others translate as “Arabians” or “merchants” (ma-arab). Jerome [Latin Vulgate translator] took it as “Orbites“as does the Arabic Version.

Jamieson-Fausset-Brown: Sending unclean birds to feed Elijah is so bizarre that many choose “Orebim,” meaning merchants, or Arabians (we-ha-ar-bim), or citizens of Arabah, near Beth-shan (ha-a-ra-bah ). But “ravens” is preferable.

Cambridge Bible: The Septuagint says “ravens.” Jerome’s biography of Paul the Hermit says a raven supplied the hermit’s wants. Observers say large birds like ravens commonly carry home large quantities of food.

Pulpit Commentary: Some say הָעֹרְבִ֣ים (ha-o-ra-bim “the ravens”) must be ravens; men – smarter and lazier – would leave enough food for several days. But if Elijah were among kinsmen, friends, or Arab Bedouin following the law of hospitality, they might visit regularly such an honored guest. Visits might be made at twilight to avoid the day’s heat or discovery by authorities. The “orabim” are not ravens but men: kinsmen, friends, Bedouins or inhabitants of Orbo near Beth-shan.

Pulpit Commentary 1 Kings 17:4, comment 4. Both a rock named Oreb and a town named Orbo were in the area. Ha-o-ra-bim “Orbites” refers to inhabitants near the rock or of the town.

Clarke’s Commentary: Bereshith Rabba, an ancient Rabbinical comment on Genesis, says [Hebrew omitted] “Air hia betachom Beithshan, veshemo Orbo.” “There is a town in the vicinity of Bethshan (Scythopolis), and its name is Orbo.”

Old Testament Israel: circled Beth-Shan, Tishbe, & Brook Cherith

(Bible-history.com)

When even professional biblical scholars, believing these passages are Holy Scripture, can’t agree whether “ravens” are really ravens, we neophytes might do best by using probability. What’s the likelihood of being fed morning and evening for a year by wild ravens, versus being fed by friendly humans, perhaps one’s own relatives? Consider what the map shows: Tishbe – the home of Elijah “the Tishbite” – lies just south of Brook Cherith in Giliad, and about twenty-three miles “as the raven flies” across the Jordan River from Beth-Shan (Orbo is in Beth-Shan’s “vicinity.”) It’s pretty clear that Elijah was hiding out in his old stomping grounds, among friends and family, no birds needed. But we report – you decide.

Other Biblical Uses for Ravens

The raven is one in a litany of reasons why Job should stop complaining about the way God treats him.

Who provideth for the raven his prey, when his young ones cry unto God, and wander for lack of food? Job 38:41 Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic Text (HSMT)

A similar metaphor is included in a litany of God’s good acts.

He giveth to the beast his food, and to the young ravens which cry.

Psalms 147:9 HSMT

Ravens will punish a wicked child.

The eye that mocketh at his father, and despiseth to obey his mother, the ravens of the valley shall pick it out, and the young vultures shall eat it. Proverbs 30:17 (HSMT)

The black color of the raven is used as a simile:

His head is as the most fine gold, his locks are curled, and black as a raven. Song of Solomon 5:11 (HSMT)

Our final raven is a parallel to last week’s citation from Matt 6:25-27, about anxiety, but this writer specifies ravens rather than the generic “birds of the air.”

Think of the ravens; they neither sow nor reap; they have no storehouse or barn; yet God feeds them. You are worth more than the birds! Is there a man among you who by anxious thought can add a foot to his height? If, then, you cannot do even a very little thing, why are you anxious about the rest? Luke 12:24-26 NEB

The bible mentions ravens eleven times. Beyond the facts that they are black, have young which cry and are fed, experience no anxiety, enjoy pecking at eyeballs, may be mistaken for one’s friends, and are unreliable errand-runners, the bible has little to say about this very intelligent, successful and admirable bird.

Bible Factoid #5 – The Bar-Abbas Mystery

Even among true believers, this is among the most debated of New Testament stories. Previously we learned: “Bar” means “son of” in Aramaic; the gospels cite Jesus – when speaking of God the Father – as saying “abba,” an Aramaic intimate word for “father;” “papa” or “daddy” is an English equivalent. “Bar-Abbas” means “son of Papa;” the “-s” ending is the Greek masculine addition. Mama, papa, baba, dada, abba – in any language, these nouns derive from baby talk, the first sounds a human infant can utter.

At the festival season it was the Governor’s custom to release one prisoner chosen by the people. There was then in custody a man of some notoriety, called Jesus Bar-Abbas (Βαραββᾶν – Barabban**). When they were assembled Pilate said to them, ‘Which would you like me to release to you – Jesus Bar-Abbas, or Jesus called Messiah?’….they said, ‘Bar-Abbas’. ‘Then what am I to do with Jesus called Messiah? Asked Pilate; and with one voice they answered ‘Crucify him!’….He then released Bar-Abbas to them; but he had Jesus flogged, and handed him over to be crucified. Matt 27:15-26 NEB

**Greek uses the -s ending when the noun is subject (nominative case), -n when noun is object (accusative case).

Barabbas mini-series poster (Crossmap.com , 2016)

There are several problems with this story. First, no written record exists anywhere – not Jewish, not Roman, not Christian – beyond this paragraph in each of the four gospels (the other three gospels borrowed from Mark) of the existence of any custom of releasing one prisoner upon request during Passover season or at any other time. Scholars not wedded to a belief in biblical literal truth and who appreciate supporting evidence doubt this story’s veracity.

Second, Jesus frequently referred to himself and others as sons or children of God the “Father” – fifty times in the four gospels. By the time he was hauled before Caiaphas the High Priest, Herod the King and Pilate the Roman Governor, this usage of “Abba” and “Father” was well known and they asked Jesus about it. Our story is saying that we now have two men called Yeshua (Jesus) Bar-Abba (Barabbas, “son-of-[intimate form of] father”). Two men called Yeshua bar-Abba – one a criminal, one a preacher.

Scholars and mystery-lovers ask: When the crowd called for Bar-Abba to be released – whom did they want, whom did they get? When they called for Yeshua to be crucified – whom did they want, whom did they get? Some scholars, including Hyam Maccoby, maintain that Jesus was commonly known as “bar-Abba” for his custom of addressing God as ‘Abba’ in prayer, and for referring to God as ‘Abba’ in his preaching. When the crowd told Pontius Pilate to “free Bar-Abba!” they meant preacher Jesus. There was no criminal Jesus present.

If we assume the story of setting one bar-Abba free is false, as many scholars maintain, why does the story exist at all? What purpose does it serve? To place blame on the Jews, many say; to make Christianity acceptable to Roman authorities. By the time the Gospels were written, Roman anti-Judaism had begun (c. 40 CE), the Jewish rebellion collapsed (66-73 CE, Jerusalem and the Second Temple were destroyed (70 AD), Masada had fallen (74 CE), the Diaspora quickened, Jews had lost favored status to practice monotheism rather than worship Roman Gods and the Emperor, and pretending to be a Jewish sect no longer protected Christians from oppression. What better way to disconnect from Judaism and curry favor with Roman authorities than to place blame for Jesus’ death onto the Jews. Thus many scholars view the gospels as partially polemic and apology, saying in effect to the Romans, “We don’t blame you, we blame the Jews. We’re no threat to you. We’re good Roman subjects. We ‘render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s…’”

The “disciple whom Jesus loved”- John 19:26 (James, John or Mary Magdalene?) sits at Jesus’ right hand, detail of Da Vinci’s Last Supper (Daily Mail)

Proffered explanations of the Bar-Abba story are legion. Here’s a sampling.

1. Two men: Yeshua crucified, Bar-Abba set free, as the Gospels say.

2. Two men: Bar-Abba crucified, Yeshua set free.

2a. Yeshua survived, met his followers afterwards, inspired them to carry on, the story ends.

2b. Yeshua went to France with or without one of the Mariams (Mary), settled down, had kids.***

3. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” religious preacher and insurrectionist, executed.

4. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” rebel insurrectionist, executed.

5. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” entire“bar-Abba” story invented to shift blame from Romans to Jewish leaders for bribing the crowd to call for the other “bar-Abba.” Pilate could release anyone, anytime without approval, permission or ceremony, and had done so previously.

6. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” Mark invented parable of Yeshua as the innocent “scapegoat” and “bar-Abba” symbolizes all sinners redeemed, set free by Yeshua’s willing sacrifice.

7. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” Greek-speaking “Mark,” utilizing story of crowd calling “bar-Abba” when asking for Yeshua’s release, invented Barbbas to explain misunderstood apparent presence of a second man.

8. One man Yeshua “bar-Abba:” Pilate (typically described as hard and iron-fisted) taunts the crowd. When they called for “son of papa” to be released, Pilate crucified him anyway.

9. The gospels are fiction: based on the life of otherwise unknown itinerant preacher.

10. The gospels are fiction: based on the life of otherwise unknown failed revolutionary.

11. The gospels are fiction: inspired by and stolen from the pre-Zorastrian religion of Mithras.

12. The gospels are fiction: “Jesus” is a corruption of name of Greek God “Zeus.”

13. And on and on and on.

***2b. This is the route followed by Holy Blood, Holy Grail (Baigent, M., Leigh, R. & Lincoln, H.), the 1982 “non-fiction” book upon which Dan Brown relied for the “factual” superstructure of his bestseller The Da Vinci Code.

Lacking adequate information, opinions proliferate and grow ever more fanciful. [Chuck Almdale]

*A Sampling of Rare Biblical Words

Raven or ravin (יִטְרָ֔ף – ytrp, “yitrap”) 1 occurrence

Crow or raven ( עֹרֵ֖ב – oreb ) 3 occurrences

A raven (הָֽעֹרֵ֑ב – ha-oreb) 1 occurrence

The ravens (הָעֹרְבִ֣ים – haorebim) 1 occurrence

And the ravens (וְהָעֹרְבִ֗ים – wehaorebim) 1 occurrence

Merchandise (מַעֲרָב– ma-arab) 9 occurrences

Citizens of Arabah (or Oreb) (הָעֲרָבָ֑ה – ha-a-ra-bah) 3 occurrences

[Chuck Almdale]

Additional Sources:

Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 14. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Christie, D.A. eds. (2009) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Corvids – Pgs 617, 630-631, 637-639.

Holy Scriptures: According to the Masoretic Text. (1955) The Jewish Publication Society of America. Philadelphia, Pa.

New English Bible with the Apocrypha, The, Oxford Study Edition. Sandmel, Samuel, Suggs, M. Jack, Tkacik, Arnold J.; eds. (1972) Oxford University Press, New York

Return To Top

Sunday Morning Bible Bird Study VI:

The Humble Hoopoe

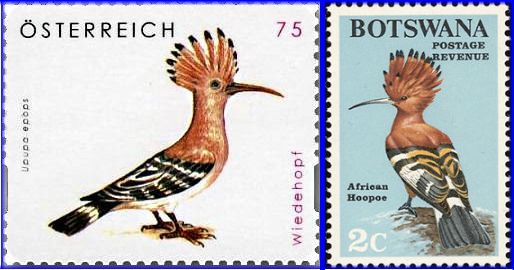

The Hoopoe is another member of the list of twenty Unclean Birds whom we’re not supposed to eat. This list comes in numerous versions due to the problems of translating ancient and rare Hebrew words, but that’s a topic for a later lesson. For now, we’ll stay with the Hoopoe, a bird common in Eurasia and Africa, yet most uncommon in ways we shall see.

And these ye shall have in detestation among the fowls; they shall not be eaten, they are a detestable thing….the hoopoe… (הַדּוּכִיפַ֖ת – had·dū·ḵî·p̄aṯ “the hoopoe”)*

Lev 11:13-19 Holy Scriptures accor4ding to the Masoretic Text (HSMT)

Of all clean birds ye may eat, but these are they of which ye shall not eat….and the hoopoe… (וְהַדּוּכִיפַ֖ת – wə·had·dū·ḵî·p̄aṯ “and the hoople”)* Deut 14:11-18 HSMT

Eurasian Hoopoe pair – Upupa epops (Henry E. Hooper)

Slightly larger than an American Robin, a Hoopoe is 11-12″ long, including its slender and slightly decurved 2″ bill. It weighs only 1½ -3 ounces, the same as your quarter-pound hamburger after cooking. The head, neck, breast and belly colors varies from rufous to cinnamon to tawny; the wings and tail are black with irregular white bands; the bill, eyes and legs are black; the long crest feathers are tipped in black. It is an attractive, lively and inquisitive bird. Its name is unlikely to be forgotten or mistaken because for most people who know it, the name is echoic of its call, which varies from hoop-hoop to oo-poo-poo. [Video & call link]

The scientific name is Upupa epops (Latin name upupam + Greek name έποπα). Some other common names are: Arabic hud-hud, Dutch hoppe, French Huppe, Italian upupa, Maltese Daqquqa tat-toppu, Polish Dudek, Portuguese poupa, Spanish Abubilla, Turkish ibibik.

They are distantly related to the kingfishers. On their “birds of prey” branch of the Tree of Life, they split from Owls 75.9 million years ago (MYA), from Trogons 72.1 MYA, from Kingfishers & Bee-eaters 69.6 MYA, from Hornbills 55.3 MYA and from Woodhoopoes & Scimitarbills 35.2 MYA. [Don’t rely on the permanence of these dates. Research continues.]

Range of the Hoopoe: Orange-breeding, Light & Dark Green-resident all year; Blue-winter; Brown – Madagascar species (Wikipedia)

Their nesting begins as early as mid-April around the Mediterranean; in Northern Europe as late as early June. Nesting behavior of non-migratory resident birds cycles around the rainy seasons. Nest are in tree cavities, walls, cliffs, earth banks or termite mounds. The female incubates 4-6 (sometimes as many as 12) blue, gray, green, yellow or brown eggs for about 18 days. The male brings her food, but no water, as they are not known to drink. They don’t remove the eggshells or fecal sacs of their young, unlike most other cavity-nesting birds. The young – helpless with sparse down when hatched – fledge (leave the nest) in 3 to 4 weeks,

Feeding the young on the fly (Cowboy54 – From The Grapevine)

and may stay with their parents until nesting season returns. They feed on the ground and use trees for safety and night roosting. Their typical flight is slow, undulating and a bit haphazard, belying their impressive speed and maneuverability should a falcon take pursuit. Their long crests – normally held flat – may be raised in excitement or alarm. They can be found alone or in small bands which are probably family units, but they are not gregarious. Hoopoes can be tamed; one became accustomed to eating a boiled egg for breakfast.

Shorebirds and waders often have chunky bodies and long slender bills, but they usually stay close to water, when not actually in it. In the Hoopoe’s preferred dry, park-like habitat, only Lapwings remotely resemble them.

Northern Lapwing – Vanellus vanellus

(John Sheppard – Sulgrave, GB)

Until recently the Hoopoe was classified into ten subspecies, but one was split off as Madagascar Hoopoe Upupa marginata (a decision lacking universal scientific agreement), leaving the rest of the Hoopoes stuck with the less euphonious name, Eurasian Hoopoe.