Snowy Plover History

Click HERE for the slideshow of banded Snowy Plovers

The following seven-part article, written in August, 2012,

first appeared on Malibu Patch, a local blogsite.

It focused on the Snowy Plover winter roosting colony

on Surfrider Beach, adjacent to Malibu Lagoon.

Part I – The Birds Themselves

Few people know it, but some very rare birds live on Surfrider Beach. They spend most of their time resting in little hollows in the sand, like the ones your heel makes. Countless people saunter through their flock, never noticing them until they scurry away from underfoot.

Western Snowy Plovers are small, even for a bird, only 6 ¼” long, much smaller than your foot. Their cryptic gray, brown, white and black plumage blends perfectly into the sandy beach. They’ll crouch for hours, motionless in sandy hollows. They’re hard to see even when searching for them.

Snowies, like all shorebirds, are carnivores; more accurately, insectivores, eating any invertebrate or tiny fish they can find. Their preferred foraging area is wrack (washed-up sea vegetation) left at the high-tide line, often abundant with kelp flies and small invertebrates. Their short stubby

bills, typical of plovers, are unlike the long and thin bills of sandpipers, who often probe – even underwater – for prey in sand and mud. Snowies don’t; they pick their food from the wrack or sand.

Because they prefer to forage in wrack,

the best feeding time is just after high tide when waves are retreating; wrack is fresh and full of living invertebrates. They will go onto wet sand to forage, but they avoid waves, however small.

The flocks of small gray-white-brown birds which rapidly scurry on little black legs, following and fleeing the wavelets as they wash in and out, will almost certainly be Sanderlings. They are slightly larger than Snowies, with long, pointed black bills. They run a lot. They resemble Snowies, feed with Snowies, even roost within Snowy flocks. It takes experience to reliably tell them apart in the field. Found nearly worldwide, Sanderlings are abundant.

Snowy Plovers are far from abundant. We’ll discuss that in a later part.

Unlike the “I’m late, I’m late” scurrying of the Sanderlings, Snowies move in a pensive, hesitant, almost thoughtful manner. They take a few steps, 3–15 perhaps, and pause, often with one leg cocked, ready for their next step, whenever they decide to take it. All of the 67 Plover species walk this way.

By the time the tide begins to rise, they’ve stopped foraging. They rest together in a small area, their roost, slightly inland of the beach berm (high ridge) between the lagoon and ocean, separated by a few inches to a few feet from one another, in small sand hollows they make, find, or improve upon. When it’s quiet with no predators or noisy humans nearby, they may sleep, although at least one lookout stays awake. When feeling frisky, they’ll chase one other around, jumping in and out of each other’s hollows.

Like you and me, Snowies need to rest and recharge their batteries. For millions of years, their lonely, windswept, barren beaches were sufficiently safe and undisturbed places to live, forage and breed. Times have changed.

Part II – History and Problems

The Plover family goes back a long way. Their oldest fossils, found in Colorado and Belgium, date from about thirty million years ago, but some scientists say they’re at least ten million years older. The Plover family is currently comprised of about 67 species (debate continues) and found on all continents and many islands except Antarctica. Nine species breed in the continental U.S. and Canada; six species appear regularly in California, four at Surfrider. The Snowy is the smallest.

The entire world population of Western Snowy Plover (WSP) – about 4,000 birds – breeds exclusively on Pacific coastal beaches: about half in the U.S. from San Francisco southward, a few farther north, the rest in Baja California. After breeding they spread out in a post-breeding dispersal to winter on sandy beaches from Puget Sound south to Central America. There is also an inland group of Snowies numbering about 18,000 birds. Many of this group winter with the WSPs in mixed flocks on western beaches but most winter on the gulf coast.

Population decline of WSPs was noticed many decades ago. Little was done until Pt. Reyes Bird Observatory (PRBO) became involved and did its first study of WSPs in 1977-80; results suggested that the birds had already disappeared from significant parts of their coastal California breeding range. Further studies were made. In 1993 WSPs were federally listed as threatened, and later listed as a Species of Special Concern by California. PRBO’s 1995 study showed a further 20% population decline since 1980.

In the early 1990’s local Malibu resident Mary Prismon, long-time member of Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society (SMBAS), began censusing the local WSP flocks at Zuma and Surfrider Beaches and reporting the results to PRBO. Her love for the birds enticed other SMBAS members to join her, until counting the birds and looking for bands became a regular part of the chapter’s activities.

In 2000, PRBO announced the first Winter Window Census of the California West Coast, set for mid-January 2001, coinciding with censuses in Washington and Oregon. Mary asked Chuck Almdale to help and, because no one else volunteered, he organized the Los Angeles County portion. He designed a protocol, divided the coastline into short segments, and found qualified volunteers to walk their segments on the same day at the same time. The weather was not good: the monthly high tide coincided with a storm surge. Nevertheless, the entire sandy beach of LA County, about 75 miles, was walked. The results were surprising.

Western Snowy Plover NO:WW, banded at Vandenberg AFB Summer 2009; wintering on Surfrider Beach (C. Almdale 11/22/09)

Part III – Nesting and Wintering

Western Snowy Plovers (WSPs) are colonial nesters, up to 246 birds nesting in close proximity. Each nest is a bare scrape in beach sand, occasionally adorned with debris, twigs and pebbles. It might, but need not, have sparse vegetation nearby. The male often makes 1-2 false scrapes nearby. Three (occasionally two) eggs are laid, buff with black marks. Both parents incubate the eggs for 27-28 days. Hatchlings are precocial –the relatively long incubation period allows them to be born downy, mobile, ready to follow their parents and find their own food. In about a month they’re full size and able to fly.

Of the estimated 50 California nesting sites used in 1970, about half are used today. In 1949, the last active nest of a Snowy Plover on L.A. County beaches was reported at Manhattan Beach. There have been no documented cases of a Snowy Plover nesting within the county since then, although no systematic survey of suitable county beaches was done between 1970 and the mid 2000s. Kiff & Nakamura (1978) held that they “probably nested at Malibu Lagoon until the 1960s when increased human use of the area displaced the birds,” but provided no supporting evidence.

As part of the ongoing PRBO study, nestlings are banded each year. Each location/year has a unique band pattern. Currently, 13 colors are used on four bands, two per leg. GG:AR means: Left leg Green above Green, Right leg Aqua above Red. This particular pattern was found last winter in the Surfrider flock; the bird was one of three banded in Summer 2011 at Oceano Dunes near Pismo Beach.

As the result of the first Winter Window Census in January, 2001, we found that WSPs in Los Angeles County were concentrated into seven locations which were their winter roosting sites; outside those locations they were extremely uncommon. We found:

| Location | Jan ’01 | Jan ‘04 |

| Zuma Beach north | 106 | 130 |

| Surfrider Beach | 2 | 33 |

| Santa Monica north | 14 | 32 |

| N. Dockweiler/MDR | 16 | 12 |

| S. Dockweiler | 18 | 13 |

| Hermosa Beach | 23 | 38 |

| Cabrillo Beach | 0 | 7 |

| Other Areas | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 179 | 265 |

Birds in 2001 at Surfrider (2) and Cabrillo (0), although seen in good numbers the previous day, were low on count day due to poor weather conditions.

To my knowledge, no one knew that Snowies stayed so close to their winter roosts. All later censuses proved that 2001 was not an anomaly. With few exceptions, the birds are just not found more than a few hundred yards – usually much less than that – from their roosting sites. Their seven roosting sites, with one exception, have not changed since then. The exception was on Dockweiler, where the roost at the foot of the hang-gliding slope disappeared when a site about ¼ mile north appeared.

Beach groomer operators on Zuma can’t see the Snowies while they remove the wrack, their food source – a double whammy!

(A. Albaisa 3/16/09)

Part IV – Population Fluctuations

As described previously, Western Snowy Plovers (WSP) wintering on Pacific beaches are extremely faithful to their roosting sites and are rarely seen outside their immediate vicinity, even as little as a few hundred yards down the beach. Northern Zuma Beach consistently has the largest wintering flock of WSPs, averaging 46% of total county birds, followed by Surfrider and Santa Monica Beaches with 14% each.

By recording bands, we discovered that there is some back-and-forth movement between Zuma, Surfrider and Santa Monica flocks. Of L.A. County’s approximately 75 miles of beach, Snowies confine themselves almost entirely to only 1.2 miles, 1.6% of the total linear beachfront. Ryan Ecological Consulting (Feb. 2010 & Nov. 2010) suggested that conservation efforts be focused on these areas, an opinion with which I heartily concur.

California’s population of WSPs fluctuates significantly seasonally and yearly:

| Year | Summer Census |

Winter Census |

Increase in Birds | LA County Winter Census |

Surfrider Census |

| 2005 | 1680 | 4261 | 2581 | 334 | 12 |

| 2006 | 1719 | 3546 | 1827 | 196 | 34 |

| 2007 | 1362 | 3290 | 1928 | 200 | 37 |

| 2008 | 1394 | 3205 | 1811 | 233 | 36 |

| 2009 | 1405 | 3379 | 1974 | 244 | 37 |

| 2010 | 1591 | 3744 | 2153 | 211 | 47 |

| 2011 | 1715 | 3763 | 2048 | 326 | 78 |

| Avg. | 1552 | 3598 | 2046 | 249 | 40 |

Summer Census: Adult WSPs counted on the California breeding grounds.

Winter Census: Total Calif. birds found during the following January’s Winter Window Census.

Increase in Birds: Winter population minus Summer population of Snowy Plovers. The increase consists primarily of young WSPs fledged that summer on the coast, plus inland race Snowy Plovers spending winter on California beaches. Some WA and OR WSPs winter in CA. Most CA WSPs winter in CA, a few winter out-of-state. As more migrate into CA for the winter than migrate out, this net increase is included in the “NewBird” numbers.

LA County Winter Census: Total birds counted in L.A. County on the Winter Window Census.

Surfrider Census: Total birds at Surfrider Beach on the Winter Window Census.

From this information, we can easily draw these conclusions:

2006-07 Winter population declined 17% from the prior winter

2007 breeding population declined 21% from the prior summer

2007-08 Winter population declined 7% from the prior winter

2008-09 Winter population declined 2.6% from prior winter

2011 breeding population has rebounded to its 2006 level

2011-12 Winter populations are still down 12% from 2005

No solid reason was ever determined for the declines. Some researchers think a Winter cold snap might have caused the initial decline in 2006-07; other researchers disagree, saying they’d already seen a decline in returning birds in Fall, 2006.

The Los Angeles County wintering population fluctuates between about 200-330 birds, averaging about 7% of the total California Snowy Plover Winter population. For the sake of comparison, this is about 2% of Malibu’s 2010 human population of 12,645.

The highest count ever recorded for Surfrider Beach was 81 birds on Jan. 22, 2012. This count included one banded bird GG:AR (previously mentioned), first appearing at Surfrider on Sep. 25, 2011 and reappearing on Christmas Day, Dec. 25, 2011. Upward trends are heartening to see, but unexpected downturns can always reoccur.

Part V – Back to Surfrider Beach

Western Snowy Plovers (WSPs) do not nest on Surfrider Beach, they roost for the winter. They begin arriving in July, numbers peak Sept-Feb, the last one leaves by May. The 2012 post-breeding arrival was first noted on July 22 when 22 were found roosting just east of the virtual enclosure erected in March 2012.

Plover volunteers, including members of Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society (SMBAS), census Snowies and search for banded birds nine months of the year. (SMBAS also does a year-round census of all birds in the lagoon vicinity.) If you see one or more people with binoculars, moving very slowly through the plover enclosure or nearby, frequently stopping and using binoculars to stare at the ground, they’re looking for banded birds.

The problem is that WSPs evolved to live on barren sandy beaches. California beaches get over 200 million visits by humans every year, humans involved in their own pursuits – surfing, swimming, sunning, walking, tossing Frisbees, letting dogs run free – humans oblivious to these tiny residents of the beach, residents who simply were not built for this. They have other problems: regular beach grooming which removes the wrack, vehicular traffic, predators attracted to human refuse. Dugan and Hubbard (2003) found that Snowy Plover abundance on southern California beaches was positively correlated with the mean cover of wrack and abundance of wrack-associated invertebrates. They also found (2009) that beach grooming increased beach erosion and the need for beach replenishment. Perhaps local beach authorities could help the plovers – which are, after all, a threatened species – as well as reduce cost for sand replenishment by ending large-scale grooming (see photo above) of the beach around plover roosting sites.

We’ve found that nearly everyone, once alerted to the presence of Snowies on the beach, will watch out for them and avoid them. Very few people enter the plover enclosures we’ve erected for them over the past few years. Unfortunately, the Snowies – despite our best efforts to teach them to read – have failed to grasp the concept and often sit outside the enclosure. We plan to move the enclosure as often as is feasible.

Very recently, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service increased by 102% the official Critical Habitat for WSPs, from 12,145 acres up to 24,547 acres of Pacific sandy beach. Surfrider Beach/Malibu Lagoon Critical Habitat was increased to about 13 acres, extending from just northeast of the pier to the colony fence. Our experience of working with the Snowies is that they rarely go beyond the area between the two lifeguard stations and much prefer the beach directly between the lagoon and ocean. In one sense, the more designated Critical Habitat, the better. In another sense, the timing of this designation hampers the reconfiguration project of the lagoon’s west channels. Snowies don’t use elevated or vegetated areas. They depend upon the open beach and the wrack.

People ask us why we bother with such small creatures. They’re not big and flashy like pandas, lions or gorillas. Our answers are numerous: they’re adorable, they are so pathetically few, few people know or care, humans caused their decline, they need our help, they’re cute, empathy for fellow earthlings, they’re wonderfully interesting to watch and know, they have engaging personalities. Each and every one of us loves these little birds.

Snowy Plover PV:YB on Surfrider Beach, banded summer 2012 at Oceano Dunes, previously sighted at Guadalupe Dunes in Aug. and at Malibu in Sept. (J. Waterman 10/22/12)

Part VI: The Plover Watchers

Over the years, many people have labored to study and save Western Snowy Plovers (WSP). Nest sites have been protected for decades; winter roosts are now known and their protection grows.

It began in the 1970’s when John and Ricky Warriner, long-term residents of Pajaro Dunes area in coastal Santa Cruz County, noticed “those little black and white creatures in the sand,” wondered about them, then became concerned for their future. They introduced Gary Page (Point Reyes Bird Observatory (PRBO) employee since 1971) to them; he too became intrigued and alarmed. [Ed. – PRBO has been renamed Point Blue.] In 1977 Page began – and still heads – PRBO’s Snowy Plover Project; they produced the first scientific study of WSPs in 1980.

In 1979, Frances Bidstrup answered a PRBO ad for WSP monitors, joined Gary and never left. Over the decades she has been: statewide volunteer recruiter, Field Biologist, WSP bander, Research Associate in charge of all WSP banding and winter sighting records. SMBAS volunteers have reported their WSP data to her for over 20 years. She loves her job and the wonderful WSP enthusiasts she meets. [Ed. – Bidstrup retired in 2016.]

When Tom Ryan arrived in 2005, the LA County WSP study and protection effort really became organized. He produced two major reports with a third coming out soon. Hundreds of local volunteers were recruited, information is continually gathered, and winter roosts are increasingly receiving protection.

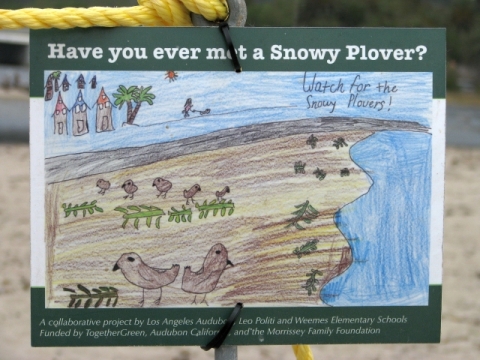

With Tom as consulting biologist,

Los Angeles Audubon Society took the WSP project under its wing in 2007, and Stacey Vigellon became the project’s Director of Interpretation. She wears many hats: biologist, educator, illustrator & designer, volunteer coordinator. She is always happy to welcome new monitoring volunteers! She says: “Plover conservation begins with public awareness. We love our beaches for summer fun, but in the off-season they are tremendous for watching wildlife. Family winter beach hikes are as enthralling as any hike in the Angeles National Forest.”

Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society (SMBAS) members have censused and searched for banded WSPs for over 20 years. In 2001, they organized the first Winter Window Census in L.A. County and kept it running until Tom Ryan arrived in 2005. Many SMBAS members work both within and outside the L.A. County WSP project, primarily at Zuma, Surfrider and Santa Monica roosts.

When Lucien Plauzoles of SMBAS censused northern Santa Monica beaches for the first Winter Window Census in 2001, he found 14 Snowies huddled together on the sand. He has been intimately involved in this roost site ever since: censusing it regularly, doing volunteer training at the site, fending off creation of a dog park nearby, getting the City of Santa Monica to erect a fence around the roost and cease beach grooming in its vicinity. He yearly attends numerous WSP local coordinating committee and range-wide (Pacific Coast) meetings.

Locally, most important and probably least known, is Mary Prismon, long-term Malibu resident and SMBAS member. Frances at PRBO recruited Mary when fellow SMBAS member Lee Oetzel needed to retire from the Zuma Beach census. On her first census in October 1992, she found 77 Snowies in the roost location they’ve used ever since. Flock size gradually increased but banded birds did not appear until 10/2/99, when PA:VO (banded Spring’99 near Moss Landing), and YB:YG (banded Spring’97 at Camp Pendleton) showed up. Banded birds have appeared regularly since then, the longest lasting being BB:OG (Oct’02 – Oct’07). In March 1994, Mary took over the Surfrider census after Barbara Elliott had to quit. Surfrider’s first banded bird was RY:RB, appearing 1/21/05 and wintering for three years. Mary kept these censuses going for almost two decades before having to quit. Mary’s fascination and love for the little birds attracted other SMBAS members, including myself, out of which developed the significant and ongoing efforts we see today throughout the county. Mary never sought recognition of any sort for herself, only help for the Western Snowy Plovers. In that she succeeded greatly.

In Los Angeles County alone, WSP volunteers number well into the hundreds; for the entire U.S. Pacific coast range, it’s in the thousands.

Part VII – The Future

In summer 2007, for unknown reasons, the breeding population of Western Snowy Plovers (WSPs) crashed 21% from the prior year high of 1719 birds. By four years later they had almost fully recovered to 1715 birds. Barring additional collapses, continued population recovery is promising. So far, Summer 2012 is looking to be even better than last year.

Taken without context, simply recovering back to the level attained five years earlier does not sound like great success. But compared to the Pt. Reyes Bird Observatory 1995 study, which found a 20% decrease from the 1980 level, simply treading water is a major success; rebounding 26% (from 1362 birds in 2007 to 1715 birds in 2011) is sufficient for exultation, with mugs of beer all around.

PRBO is currently monitoring the breeding colonies and banding nestlings at Ocean Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area in San Luis Obispo County, Vandenberg Air Force Base in Santa Barbara County, and the shores of Monterey Bay in Santa Cruz and Monterey counties. They work with government agencies in each area to promote the conservation of the plover and its habitat.

In Los Angeles County, protection at winter roosts is in place in three locations: Surfrider Beach, Santa Monica Beach and northern Dockweiler Beach. The fences have signs informing the public about the Snowies. As yet, we have not been able to establish winter roost protection at the Zuma, southern Dockweiler, Hermosa Beach or Cabrillo sites.

Gary Page, founder and head of PRBO’s WSP Project, puts his hopes for the future of the Western Snowy Plovers succinctly: “Snowy Plover population recovers and no longer needs to be listed.”

For that to happen, the birds need the cooperation of the human population with whom they share the beach. We need to back off from them, just a little bit, and give them room to carry on their lives, to nest and raise their young, to forage for food, to rest and to sleep without the threat of being trampled at any moment. We need to stop removing the wrack (sea vegetation) lying on the beach near their nesting and roosting areas. We need to keep our dogs, our boisterous children, our vehicles and our trash away from them. If we can do that, most likely they’ll be able to bring off their own recovery without additional interference from us.

We hope that now that you know the Snowies are there, and why they’re there, you too will come to appreciate them and watch out for them. They need your concern.

Many thanks to the following people who answered questions and supplied background information: Gary Page and Frances Bidstrup, PRBO; Tom Ryan & Stacey Vigallon of Los Angeles Audubon Society Western Snowy Plover Project, Lu Plauzoles & Mary Prismon, Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society.

Sources and recommended sites for additional information

Western Snowy Plover – Tools and Resources for Recovery

http://www.westernsnowyplover.org/

Western Snowy Plover Natural History and Population Trends

http://www.westernsnowyplover.org/pdfs/plover_natural_history.pdf

Appendix B. Birds of Malibu Lagoon.

Dan Cooper, Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc.

http://www.cooperecological.com/birds_of_malibu_lagoon_8_06.htm

Los Angeles Audubon Society – Western Snowy Plover Conservation Page.

http://losangelesaudubon.org/conservation-a-restoration-mainmenu-82/154/268-snowy-plover

The Western Snowy Plover in Los Angeles County, California.

Ryan Ecological Consulting

http://losangelesaudubon.org/images/stories/pdf/westernsnowyploverin%20losangelescounty.pdf

The Western Snowy Plover in Los Angeles County, California: January to August 2010. Ryan Ecological Consulting

http://losangelesaudubon.org/images/stories/pdf/snplannualreport_2010finalweb.pdf

Pt. Reyes Bird Observatory (Excel Spreadsheets)

2010-11 California Winter Snowy Plover Survey.

2012 Summer Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2005-2011 Results for Comparison.

[by Chuck Almdale]

Well done Chuck!

LikeLike