From the Bible to Molecular Clocks | Taxonomy 1

[By Chuck Almdale]

How names began: One early explanation

Among humanity’s most notable characteristics is our ability to learn names and our unquenchable drive to name things. And what are nouns, verbs and adjectives but names for things, actions and qualities? Over 2,500 years ago some member or members of a Middle Eastern tribe, while musing on life in general and how the human race in particular came into being and what they got up to at the very beginning of time, composed the following:

So God formed out of the ground all the wild animals and all the birds of heaven. He brought them to the man to see what he would call them, and whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name. Thus the man gave names to all cattle, to the birds of heaven, and to every wild animal…

— Genesis 2:19-20 NEB —

The writer(s) of the Jewish Scriptures imagined that among the very first things that the very first human did was…name things. That’s how critically important and utterly typical of humans this behavior is. Our ability and need to name and communicate are at the top of the list of things that make us human and helped our ancestors to survive in a lion-eats-man-and-jackal-gnaws-the-bones world. We’ve known that since before written history began, and we’re still busily finding or creating new things to name and then going on to name them. There are over 7,000 languages in use today. English, the most popular second language for most of the world, has a vocabulary of over 1 million words. Although no one knows or uses them all, each word was concocted by some person for what seemed to them a perfectly good reason.

In a recent TV science program, a speaker from a small cultural group said (I paraphrase), “In our culture we give ourselves permission to see similarities between things and not dwell on differences. We might say a tree and an animal and a person are kin.” But that’s not special or unusual; we all do that, we always have. Logically speaking, you can’t classify words or what they refer to into a group with shared traits or a “unity” without simultaneously excluding words/things that don’t share those traits. Inclusion and exclusion are simultaneous and mutually dependent activities.

This blog series is about not only the naming of things, but the development and application of a particular rational system, a schema, a science, for the naming of things. For those not familiar with this system, this series will introduce you to the structure, its application, some of the most recent changes in the system and some of its problems. We often forget that alike and unalike are far more than a simple binary. Same<——>Different is a spectrum: to be truly useful, scientific nomenclature should incorporate, if possible, the degree of similarity and dissimilarity.

The Naming and Classification of Organisms

If it is true that to know something you must first name it, then Linnaeus made the plant kingdom knowable. — Christopher Joyce, Earthly Goods, 1994

Prior to the appearance of Carl Linnaeus on the world scientific scene, taxonomy existed in a series of rudimentary forms. Over 2,300 years ago Aristotle created his “Great Chain of Being;” eleven levels classifying all life according to simplicity and complexity, as he perceived it. Plants were at the bottom, followed by animals, then humans, and finally angels and other supernatural beings at the top, of course, right where everyone knew they belonged. He also applied the term species to any particular identifiable organism, and genus for a collection of organisms with a shared set of traits. Later philosophers created their own systems, usually beginning at the top with a few large groups (plants, animals, birds, fish, etc.) and subdividing their way down to individual organisms. Descriptions and even the names of organisms could get quite lengthy. I read long ago that prior to Linnaeus one such “descriptive-name” for the European Robin (Erithacus rubecula) ran to over a page of text; the fact that the breast was red was not mentioned until somewhere on page two. That’s not terrifically useful.

By the 18th Century and due in part to the explosive growth of international trade and exploration, European scientists were drowning in a sea of new organisms with no good system to organize them, until the arrival of Carl (or Carolus) Linnaeus (1707-1778). Linnaeus recognized his mission in life and wrote of himself, Deus creavit, Linnaeus disposuit (“God created, Linnaeus organized”). Linnaeus was a thoroughgoing Christian who believed both in God’s creation and that there were no deeper relationships to be expressed than what could be seen in nature. All we needed to do was look deeply and record what we saw, no small task. In 1735 he presented the first edition of his Systema Naturæ, consisting of eleven large pages listing the plants and animals which he had so far identified. His book provided descriptive identification keys enabling readers to identify animals and plants. For plants he made use of previously ignored smaller parts of the flower.

Among Linnaeus’ greatest concerns and contributions to science was his gradual adoption of Aristotle’s system of giving each organism a unique scientific name, using only Latin (and/or Latinized Greek), which was the language of philosophy, religion and science throughout Europe at the time. He used Aristotle’s terms: species to refer to a particular organism, and genus for a general grouping of organisms with a shared set of traits. As new organisms were described and placed into a group (genus), his list (or key) of differentiating descriptions grew longer. To make the list easier to use, Linnaeus printed in the margin two names, the name of the genus and one word from the list of differences or from some former name. This latter word became the more specific name, the species.

This became the scientific binomial system of nomenclature we still use today; “two names,” with the first generic name capitalized, the second specific name not capitalized, e.g. Homo sapiens and Passer domesticus.

For higher organization Linnaeus created a nested hierarchy with three kingdoms at the top: Regnum Animale (animal), Regnum Vegetabile (plants) and Regnum Lapideum (mineral). Below that were two additional ranks of Class and Order, followed by the binomial of Genus and Species. Below species he sometimes recognized a rank now standardized as variety in botany and subspecies in zoology. At the start Linnaeus was certain the number of organisms in the world could not possibly exceed 10,000, and he devoutly wished to see them all named and described within his lifetime. By the time he died in 1778, his Systema Naturæ in its 12th edition (1766-1768) had grown to 2,400 pages and contained over 12,000 organisms.

Table of the Animal Kingdom (Regnum Animale) from Carolus Linnaeus’s first edition (1735) of Systema Naturae. Subdivision first column Quadrupedia: Anthropomorpha (Man, apes, sloth), Ferae (wild animals), Glires (= mice), Jumenta (pack animals), Pecora (cattle) and Paradoxa. Go to the Wikipedia photo, zoom in and actually read it.

Over the past 250 years, the Linnaean system has expanded significantly and codified with rules governing priority of names and the official adding of dates and describer. The term “Phylum” was coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 and soon widely adopted, and in 1883 August W. Eichler added its equivalent of “division” to plant taxonomy. The term “Family” was first used by French botanist Pierre Magnol in 1689; Carl Linnaeus had used it in 1751 in his Philosophia Botanica to categorize significant plant groups such as trees, herbs, ferns and palms; it appeared in French botanical publications, from 1763 to the end of the 19th century as an equivalent to order (Latin ordo); finally, in Zoology it was introduced as a rank between order and genus in 1796 by Pierre André Latreille. There are currently approximately 1.8 million scientifically described (and duly named) organisms. Estimates of remaining unnamed animal species alone ranges from five to thirty million. Feel free to make your own guess. Don’t even think about the unnamed bacteria species; there could be billions.

For well over a century the zoological divisions consisted of: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species (and subspecies, but ignore that for this paragraph). As in the study of medicine, mnemonics were invented to help memorize this: King Philip Came Over For Good Soup, or Keep Pot Clean Otherwise Family Gets Sick. The version I learned in California was: Keep Police Cars On Fresno’s Great Streets. There are doubtless many mnemonics in many languages. Use whatever works for you, but such a mnemonic really does help to learn the sequence, and knowing the sequence will vastly enhance your enjoyment of whatever you wish to learn in biology, as well as help you get through the rest of this blog series.

Microscopes were invented and improved and became widely available. In recent decades they became immensely more powerful and innumerable microscopic organisms – the Prokaryotes – were discovered. The microscopic Prokaryotes – unicellular organisms which lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles – were then discovered to be of [at least] two kinds.To locate these new, fundamentally different organisms on the developing “tree of life” a new top rank of Domain was added. Further research demonstrated that these two kinds of Prokaryote were sufficiently and fundamentally different from one another for each to warrant their own domain.

Not to worry: If you add Do or Did to the beginning of your mnemonic you’ll keep it accurate.

Evolutionary Clocks

Until the 1960’s our understanding of relationships between various species, genera, families and orders was based on morphology, the study of the form and structure of organisms, and especially on comparative morphology, the analysis of the patterns of structures and their locations within an organism’s body plan and their similarity/dissimilarity to other organisms. Paleontologists and comparative morphologists studied bones from animals living and extinct and made educated guesses about how closely they were related and how long ago their common ancestor might have lived. In our own crude way everyone does this: obviously fish are more closely related to other fish than to mammals, just look at them with their fins and gills!; wolves and coyotes are closer to each other than to cats; gulls and terns are closer to each other than to sandpipers; whales and sharks are closer to each other than to hippos. Well, not that last one, but the morphologists dug deeply into the details and by current standards got most of it right.

In 1962, while studying amino acids in hemoglobin in different animal species, Linus Pauling and Émile Zuckerkandl noticed that the number of hemoglobin amino acid differences between lineages changed linearly over time, as estimated from fossil evidence. This suggested that the rate of evolutionary change of any specific protein was approximately constant over time and over different lineages. If valid, this finding could be used as a “molecular clock” to date evolutionary change: to estimate time since two lineages diverged and to calculate “genetic drift,” the neutral changes that don’t affect DNA functioning. In 1964 they presented their highly influential paper “Evolutionary Divergence and Convergence in Proteins,” which introduced the term “evolutionary clock” and presented a derivation of its basic mathematical form.

Soon afterward, in 1963, Emanuel Margoliash made a critical discovery, the genetic equidistance phenomena. He wrote:

“It appears that the number of residue differences between cytochrome c* of any two species is mostly conditioned by the time elapsed since the lines of evolution leading to these two species originally diverged. If this is correct, the cytochrome c of all mammals should be equally different from the cytochrome c of all birds. Since fish diverges from the main stem of vertebrate evolution earlier than either birds or mammals, the cytochrome c of both mammals and birds should be equally different from the cytochrome c of fish. Similarly, all vertebrate cytochrome c should be equally different from the yeast protein.” — Wikipedia: Molecular Clock

*Note: Cytochrome c is a small hemeprotein found loosely associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion (an organelle within cells called the “powerhouse of the cell” with its own DNA) where it plays a critical role in cellular respiration.

Because all eukaryotes (organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus) contain cytochrome c, it became the basis of biological molecular clock research. For example, the difference between a carp’s cytochrome c and that of a frog, turtle, chicken, rabbit or horse is a very constant 13% to 14%. Similarly, the difference between a bacterium’s cytochrome c and that of yeast, wheat, moth, tuna, pigeon or horse ranges from 64% to 69%. In other words, every species on one branch of the “tree of life” is equally distant from every species on a different branch.

In 1967 Vincent Sarich and Allan Wilson were comparing albumin proteins of primate lineages to a more-distant lineage and discovered that these proteins had approximately constant rates of change in modern primate lineages. Humans and chimpanzees were about equally distant from New World Monkeys (Ceboidea), and they estimated that humans and chimpanzees diverged only ~4–6 million years ago (mya). It was later discovered that the molecular clocks of most lineages needed to be calibrated with independent evidence about dates, primarily from the fossil record.

In the last twenty years, other molecular clocks have appeared and morphology continues to be used. Two examples:

1. The cladogram [Link] I used for most of the detail (Palaeognathae and Galloanseres excepted – you’ll see) of the cladogram presented in posting nine in this series came from a paper published in October 2015 and was based on ~30 million pairs of genomic (chromosomal) DNA, rather than on proteins. This is a new development in biological molecular clocks.

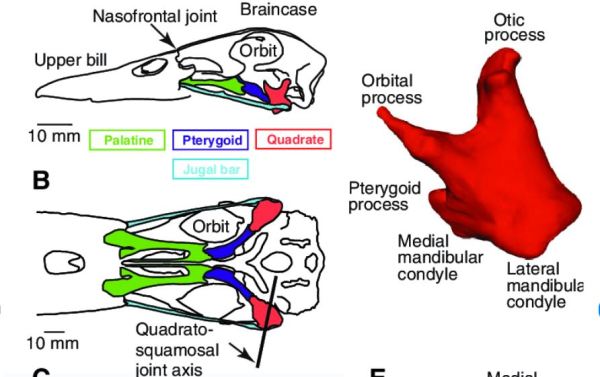

2. The quadrate bone in the jaws of all reptiles and birds has been used to study the relationship of Anseriformes (ducks & allies) to Galliformes (chickens & allies). Such studies, when combined with molecular clock studies, indicate that these two orders are not only each other’s closest relatives, but that they are more closely related to their reptilian ancestors than the other members of their Neognathe group. For this characteristic they were placed in their own Clade Galloanseres. We’ll mention this again when we get to the Galloanseres clade in the Neoaves cladogram in posting nine.

The Taxonomy Series

Installments post ever other day; installments will not open until posted.

Taxonomy One: A brief survey of the history and wherefores of taxonomy: Aristotle, Linnaeus and his binomial system of nomenclature, taxonomic ranks and the discovery and application of biological clocks.

Taxonomy Two: Introduces the higher levels of current taxonomy: the three Domains and the four Kingdoms. We briefly discuss Kingdom Protista, then the seven phyla of Kingdom Fungi.

Taxonomy Three: Kingdom Plantae.

Taxonomy Four: Kingdom Animalia to Phylum Annelida.

Taxonomy Five: A discussion of Cladistics, how it works and why it is becoming ever more important.

Taxonomy Six: Phylum Chordata, stopping at Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Seven: Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Eight: Class Aves, beginning with a comparison of five different avian checklists of the past 50 years.

Taxonomy Nine: A cladogram and discussion of Subclass Neornithes (modern birds) of the past 110 million years, reaching down to the current forty-one orders of birds.

Taxonomy Ten: A checklist of Neornithes including all ranks and clades down to the rank of the current 251 families of birds (plus a few probable new arrivals) with totals of the current 11,017 species of birds.

Reference Paper

*The Origin and Diversification of Birds. Stephen L. Brusatte, Jingmai K. O’Connor, and Erich D. Jarvis. Current Biology Review; Vol. 25, Issue 19; 5 Oct 2015, figure 6.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982215009458

Discover more from SANTA MONICA BAY AUDUBON SOCIETY BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.