Cladogram of forty-one Avian Orders | Taxonomy 9

[By Chuck Almdale]

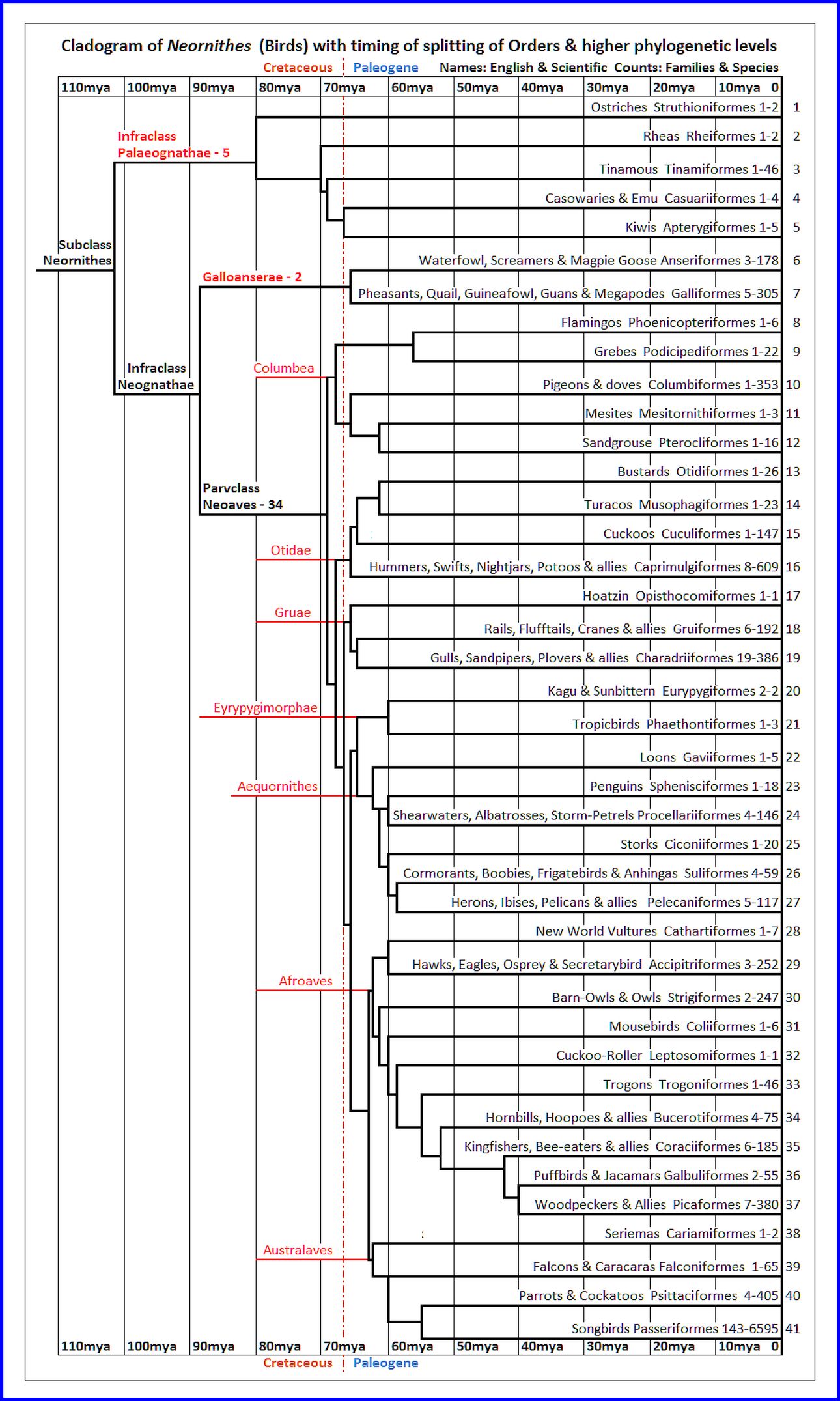

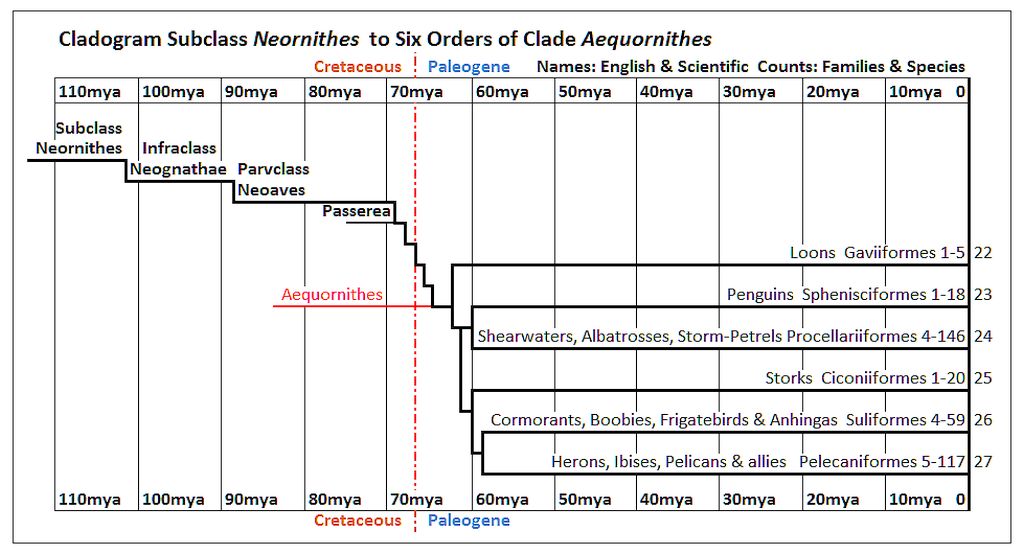

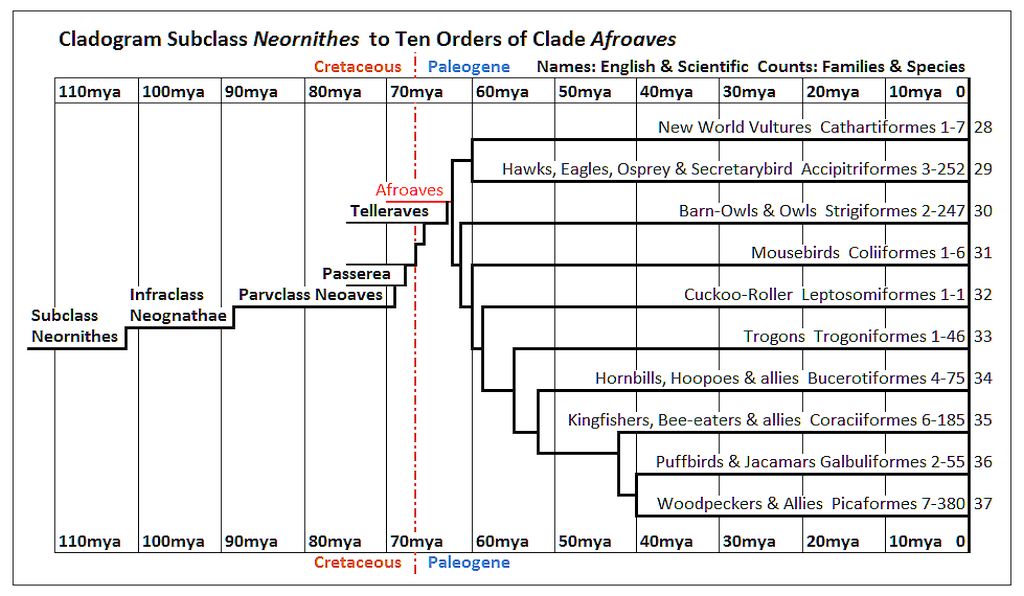

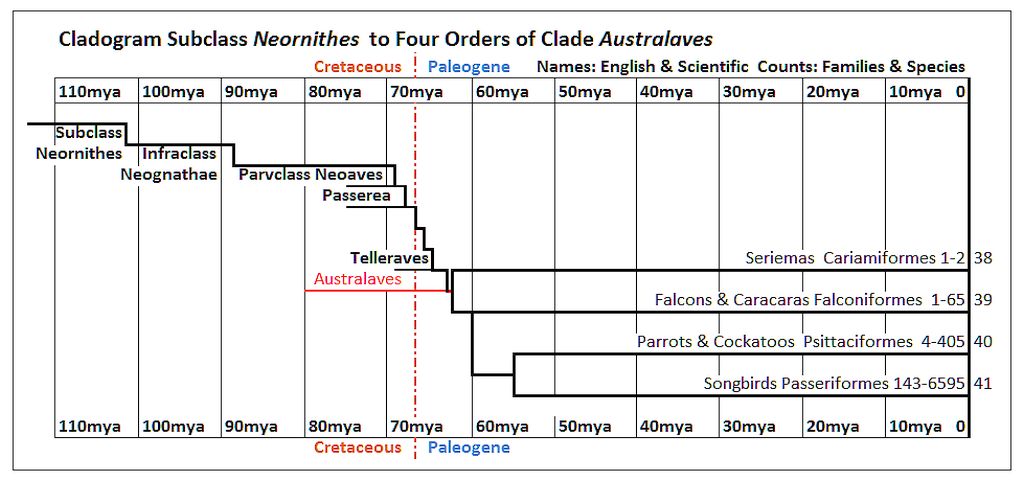

Presented below is a cladogram of the forty-one currently recognized Orders of birds. A cladogram is a graphic representation of relationships between organisms with one of the axes, in this case the horizontal, capable of representing the passage of time, if the designer chooses to do so. For those unfamiliar with cladograms in general, Taxonomy 5 on cladistics will help; this cladogram’s significant features are also listed below. Frequent referral to the cladogram should clarify the descriptions of the clades.

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event

Asteroid strikes the earth 66 mya; not an actual photograph of the event. Wikipedia: K-Pg Extinction Event

Critically important in the evolution of birds was the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, perhaps better known by the prior term Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) extinction. (Cretaceous is spelled with a “K” in German). Approximately 66 million years ago an asteroid smashed into the earth where the Gulf of Mexico now lies, throwing an immense quantity of water, rock and dirt into the atmosphere. This material spread by winds around the earth, causing a “nuclear-winter”-type worldwide blackout that wiped out an estimated three-quarters of plant and animal species on earth. All non-avian dinosaurs became extinct as did most tetrapods weighing over 55 pounds (25 kg), excepting a few cold-blooded species such as sea turtles and crocodilians. This marks the end of the Cretaceous period and the entire Mesozoic era and the beginning of the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era, our current geological era. The asteroid impact left a thin layer of sediment – the K–Pg (K–T) boundary, found worldwide in marine and terrestrial rocks – which contains high levels of iridium, a metal more common in asteroids than in the Earth’s crust. Many of the avian clade evolutionary divergences displayed in the cladogram occurred at or very shortly after this event.

Features of the Cladogram

K-Pg (K-T) event: This is marked by a vertical broken orange line.

Timescale: At top and bottom, 110 million years ago on left, current day on right.

41 Orders: Listed on right side, generally the most ancient at top, the youngest at bottom, numbered on right margin. For three higher ranks the number of orders they contain is listed, e.g. Parvclass Neoaves – 34.

Families & Species: Listed next to the Order name, e.g. “Rheas Rheiformes 1-2” means 1 family, 2 species within Order Rheiformes.

Heavy Dark Lines: The branches of the evolutionary tree. The tree starts near the upper left with Subclass Neornithes, appearing 110-101 million years ago, and branches right with branch tips ending at the current 41 Orders.

Nine Clades: In red. the same nine clades used in the chart of five checklists presented in Taxonomy 8.

The Diversification Cluster: Many major lineage divisions occurred within a few million years following the K-Pg extinction event.

The cladogram was created in MS Excel.

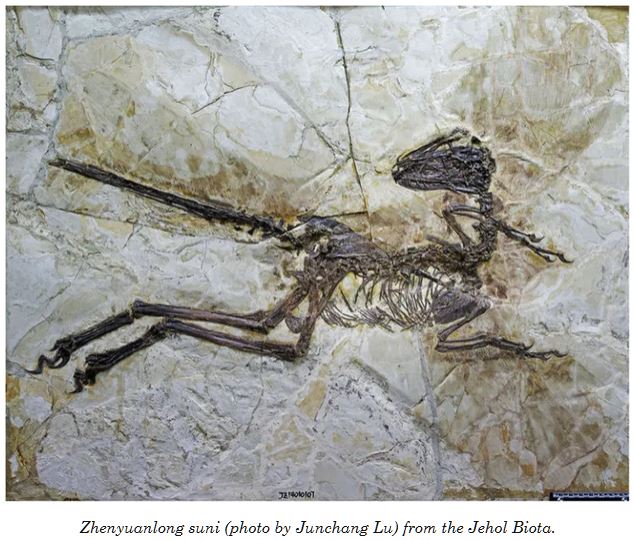

Overview of Class Aves to Subclass Neornithes

The biological Class Aves includes fossil groups of birds as well as modern taxa. It is generally considered to have emerged out of the Theropod (bipedal carnivorous) dinosaurs 150 million years ago (mya), with Archaeopteryx, the feathered, toothed and bony-tailed dinosaur as the first of its kind. Archaeopteryx could not lift its wings above its back, but could flap downward, and it’s now believed it could fly a bit like a pheasant, with short bursts of active flight as well as short glides. Recent X-ray studies revealed nearly hollow bones. It had asymmetrical feathers suggesting flight ability; flightless birds have symmetrical wing feathers (except for those lacking wings). Scientists are still debating how it got into the air: did it run, leap from a perch or wait for a strong breeze? The question of whether it should be considered a dinosaur or the first bird is also up in the air. Others avians appeared during the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous periods (150 – 110 mya); all are extinct and are placed in Subclass Archaeornithes (not on this cladogram). This leaves remaining the line leading to the as-yet-extant species, Subclass Neornithes, located at upper left in the cladogram below.

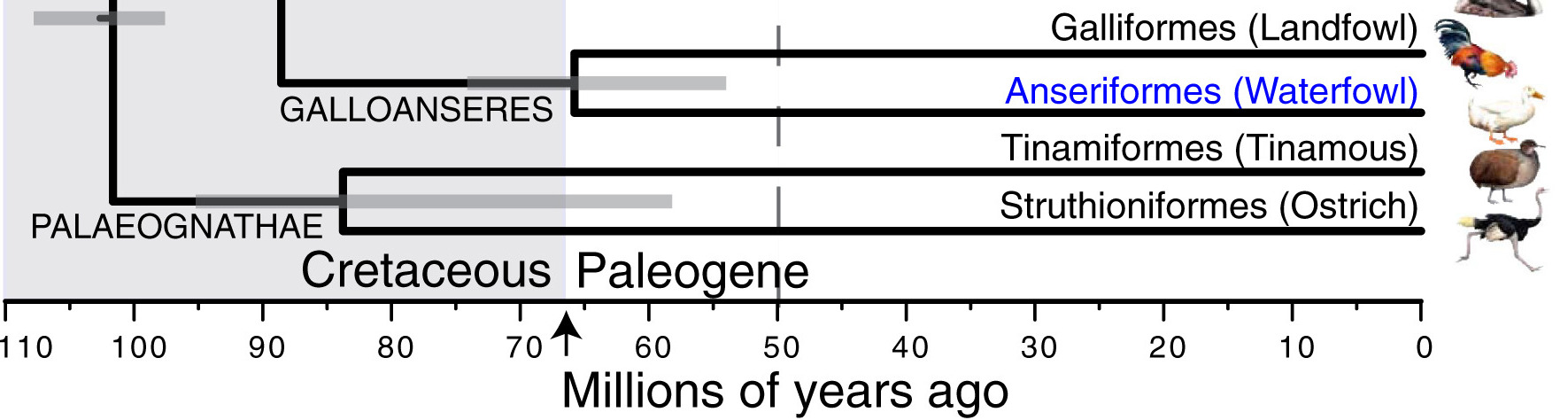

Subclass Neornithes includes all extant avian species. The earliest divergence within Neornithes, around 102 mya, split Infraclass Paleognathae (ratites and tinamous) from Infraclass Neognathae. Neognathae include two primary major groups of birds, Parvclass Galloanserae and Parvclass Neoaves. Galloanserae in turn is composed of two Orders, Anseriformes (waterfowl) and Galliformes (chickens and allies). All other modern birds fall into Parvclass Neoaves.

The information in the Subclass Neornithes cladogram below is relatively up-to-date (new information keeps pouring in), and comes from a variety of sources. The currently accepted 41 orders of bird appear roughly in sequence of oldest to youngest, and fall into nine major clades (in red). Credible dates of appearance (e.g. 60 mya) of any clade can vary 5% (e.g. 63-57 mya) from dates indicated.

To print or save an image of the chart: click here.

Increase chart size: <Control> +; Decrease: <Control> -.

The rest of this post discusses the nine clades (above in red), each beginning with a excerpt from the main cladogram.

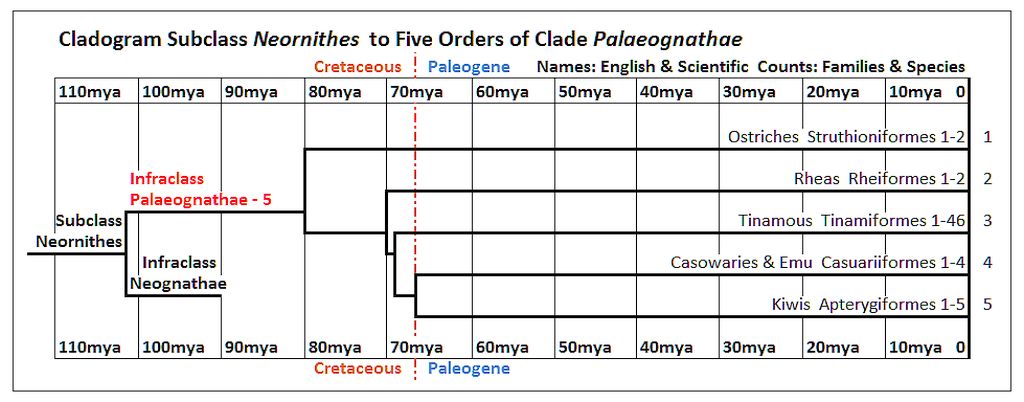

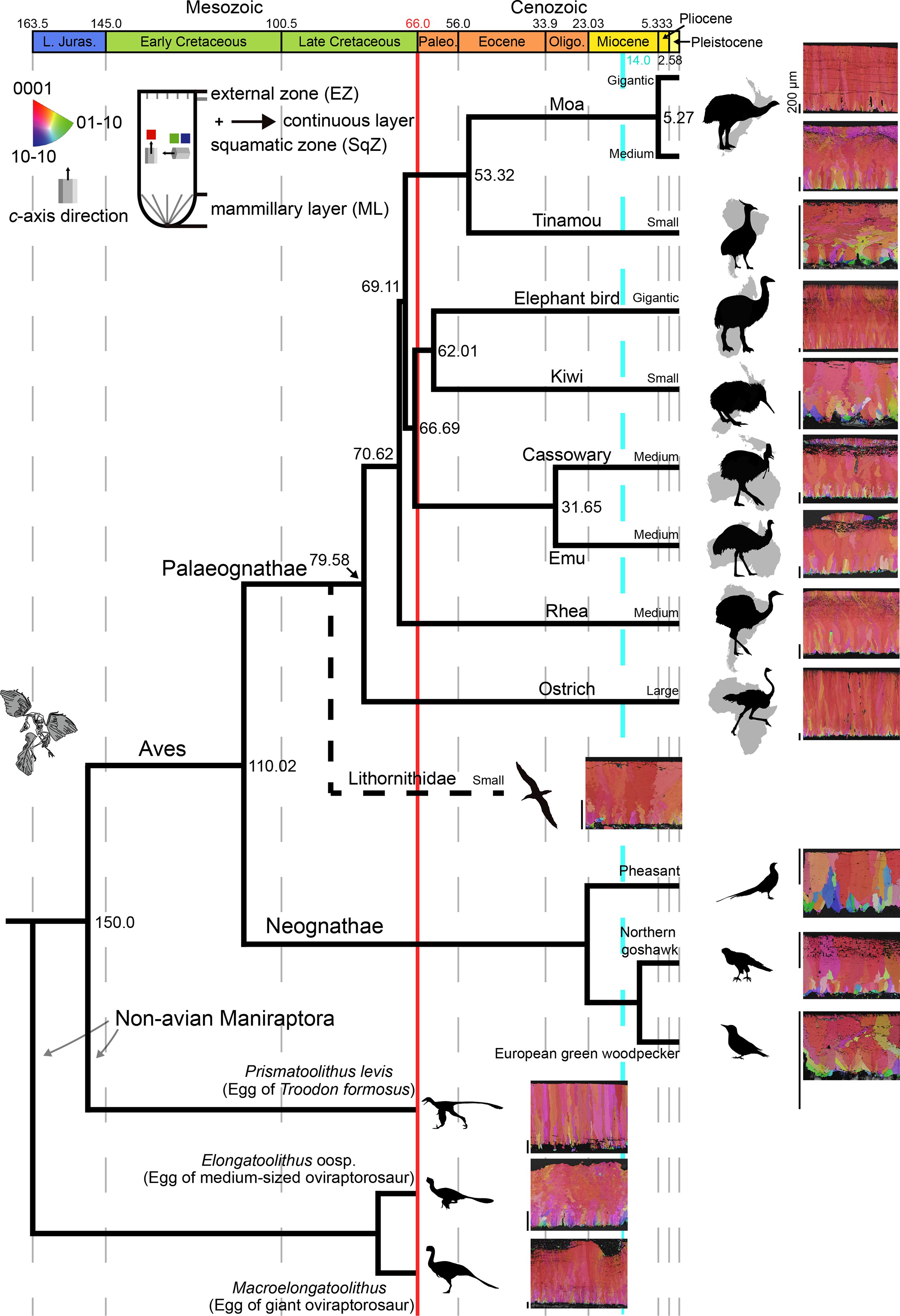

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Palaeognathae

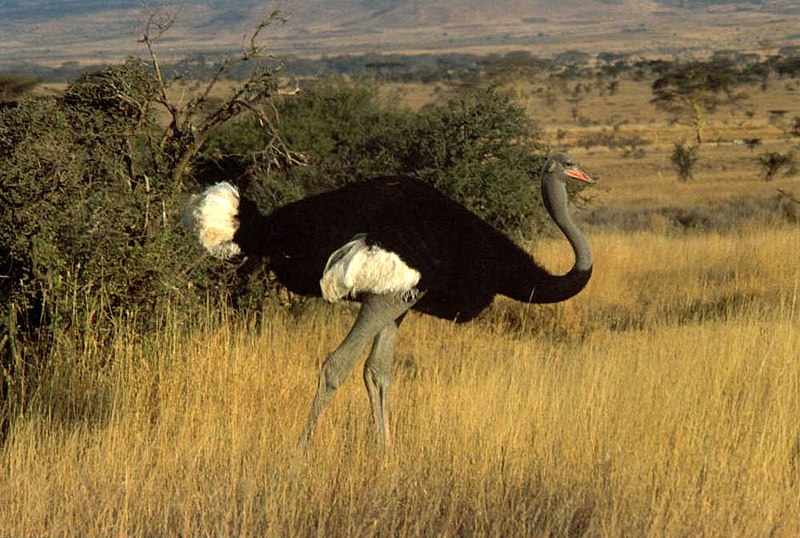

About 102 million years ago, birds began to diversify into two major clades, the Palaeognathae and the Neognathae. The small clade of Palaeognathae began diversifying about 80 million years ago (mya) and is currently comprised of five of the most ancient orders of birds. The line leading to modern Struthioniformes (Ostriches) was the first to diverge 80 mya, followed by the Rheiformes (Rheas in South America) around 71 mya, then the Tinamiformes (Tinamous of Central and South America) at 69 mya, leaving Superorder Apterygimorphae, consisting of the Orders of Apterygiformes (Kiwis) and Casuariiformes (Cassowaries and Emu). These last two orders diverged from one another at the K-Pg extinction event 66 mya. The Emu later diverged (not shown here) from Cassowaries around 32 mya. Today the Palaeognathae contains 5 orders, 5 families and 59 species, 46 of them Tinamous. There are no monotypic families.

Somali Ostrich, getting closer to extinction.

Photo: Christiaan Kooyman, Jan. 2003. Wikipedia: Somali Ostrich

Cladogram used as source for Palaeognathae splits

Diagram from: Microstructural and crystallographic evolution of palaeognath (Aves) eggshells. Seung Choi, Mark E Hauber, Lucas J Legendre, Noe-Heon Kim, Yuong-Nam Lee, David J Varricchio. Jan 31, 2023.

Link: https://elifesciences.org/articles/81092 scroll to Fig. 13 about 1/3rd way down.

There is a potential problem with the Palaeognathae cladogram directly above, also depicted in the Palaeognathae portions of the Neornithes cladograms. Ostriches, Rheas, Cassowaries, Emu and Kiwis were long considered to be each other’s closest relatives and constituted the Ratites, flightless birds with a flat (not keeled) sternum (breastbone). The sternal keel – possessed by all flying birds – provides additional bone attachment surface for breast muscles. However, Tinamous are not flightless and possess a sternal keel: they don’t like to fly and prefer running or walking away silently into the forest or grassland, never to be seen but only heard, but can fly when necessary. But if the Tinamou line is embedded within the ratites – now described as “mostly flightless” in order to accommodate the capable-of-flight Tinamous – it means Tinamous developed their sternal keel separately from the Neognathae, the clade which includes all birds except the ratites and tinamous. The depicted schema also has Tinamous, Cassowaries, Emu and Kiwis diverging from Rheas around 70 mya. But Tinamous and Rheas are currently endemic to the Americas, while the other three groups live in Australia, New Guinea and New Zealand. Based on geography, one might assume that a Tinamou-Rhea group diverged from a Cassowary-Emu-Kiwi group, then each group continued their own divergences. Yet a 2010 study suggests that the extinct Moa of New Zealand is the Tinamou’s closest relative. All of these birds have a similar and distinctive Palaeognath palate. Supercontinent Gondwana didn’t finish breaking up into Africa, India, Australia, South America and Antarctica until after – perhaps well after – the start of the Paleogene (66 mya), so these flightless birds had many millions of years to walk to their current ranges from wherever in Gondwana they began. The current opinion holds that the ratites developed flightlessness several times; it may be that flight developed several times as well (Tinamous and Neognathae). However, if some of the dating studies are inaccurate, it may yet be that the Tinamous were first to diverge from the rest of the Palaeognaths (or vice-versa which amounts to the same thing, but suggests that the ratites developed from a flying ancestor), a possibility depicted occurring about 84 mya in the partial cladogram below.

Ordinal-level genome-scale family tree of modern birds. The Origin and Diversification of Birds. Stephen L. Brusatte, Jingmai K. O’Connor, and Erich D. Jarvis. Current Biology Review; Vol. 25, Issue 19; 5 Oct 2015, figure 6. [Link]

What these Palaeognaths do have in common is indicated by their name which means “ancient jaw”: the bones of their palate are described as retaining basal (primitive) morphological characteristics, thus closer to the reptilian palate than that of the birds in Infraclass Neognathae (“new jaw”).

It seems there may still be details to be worked out with the Palaeognathae relationships among themselves and with the Neognathae. “Early days” perhaps, as they say in BBC police shows, meaning “We’re still working on it, please stop asking and go away.”

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae

The clade Infraclass Neognathae is the sister taxon to Infraclass Palaeognathae. This clade contains the remaining 36 orders of birds and the rest of the approximately 11,000 (a perpetually increasing number) species of birds. This clade – some say Infraclass, others say Parvclass and still others simply leave it as a clade – diverged from the Palaeognathae 102 mya and began diversifying into two clades around 88 million years ago. The smaller of these two clades is Parvclass Galloanserae, consisting of two orders and 483 species, and the much larger Parvclass Neoaves consisting of the remaining 34 orders.

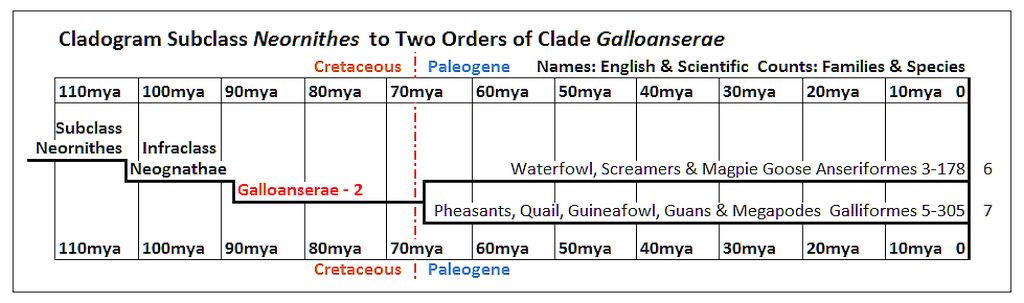

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Galloanseres

Parvclass Galloanserae diverged from the rest of Neognathae 88 million years ago, when a major breakup within the supercontinent Gondwana occurred. The Galloanseres lineage began their diverging into two orders at the start of the Paleogene Period (66-23 mya): Anseriformes consisting of Waterfowl, Screamers (South America) and the Magpie-Goose (Australia), 3 families totaling 178 species; the other is Galliformes, a diverse worldwide order containing Pheasants, Quail, Guineafowl (Africa), Guans (Central & South America) and Megapodes (Australasia), 5 families totaling 305 species. The Megapodes have the unique behavior of not sitting on their eggs but using warm earth, fermenting vegetation or geothermal heat to incubate them. Later Galloanserae diversification followed their dispersal to the various continents and islands during the Eocene (56-33.9 mya). The monophyletic (one lineage) relationship of these two orders and their placement as the closest relative (sister taxon) of Neoaves are well supported. Background: Waterfowl and Gamefowl (Galloanserea); Pereira, Sergio L. & Baker, Allan J.; page 416, Link: Timetree.temple

The largest families are Phasianidae (Pheasants & allies, 186 species) and Anatidae (Ducks & allies, 174 species). Family Anseranatidae (Magpie Goose of Australia) is monotypic.

Magpie Goose (Anseranas semipalmata), a monotypic family of northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

Photo: JJ Harrison, Dec. 2019. Wikipedia: Magpie Goose

As mentioned previously, molecular clocks aren’t the only factor in drawing up cladograms which include dates on the nodes of divergence; morphology is still important, especially when it comes to calibrating a lineage’s molecular clock. Following are two examples of how morphological studies are still being used.

Vegavis the Neoornithine

Vegavis fossil from Letters from Gondwana. Source: Paleonerdish OK

Although a Cenozoic origin for Galloanserae has been long hypothesized based on fragmentary and incomplete specimens, definitive evidence was found only recently. Vegavis iaii, the oldest known anseriform fossil from the Maastrichtian stage (72.1-66 mya) of the late Cretaceous, is closely related to the lineage of ducks and geese. This finding implies that modern anseriform families, and hence their closest living relative, the Galliformes, were already independent lineages in the late Cretaceous. From: Waterfowl and Gamefowl (Galloanserea); Pereira, Sergio L. & Baker, Allan J.; page 416, Link: Timetree.temple

The single best record of a Cretaceous neornithine is the partial skeleton of Vegavis from the last sliver of the Cretaceous period (around 68–66 million years ago) in Antarctica. This bird is assigned to the Neornithes subgroup of modern birds known as Galloanserae which includes Anseriformes (ducks and geese) based on the morphology of its well-developed hypotarsus.

Source: The Origin and Diversification of Birds. Stephen L. Brusatte, Jingmai K. O’Connor, and Erich D. Jarvis. Current Biology Review; Vol. 25, Issue 19; 5 Oct 2015, page. [Link]

The Hypotarsus

Hypotarsus process on the tarsometatarsus. Pinterest: Mark Kobelka

The hypotarsus is a process [bony bump] on the posterior side of the upper end of the tarsometatarsus (the long bone immediately above the foot) of many birds; aka the calcaneal process. A protruding hypotarsus “enhances the capacity of diving birds to propel their feet backward and power underwater swimming.”

Source: Research Gate, Comparative hindlimb myology of foot‐propelled swimming birds, article by Glenna T. Clifton, Jennifer A Carr & Andrew A Biewener.

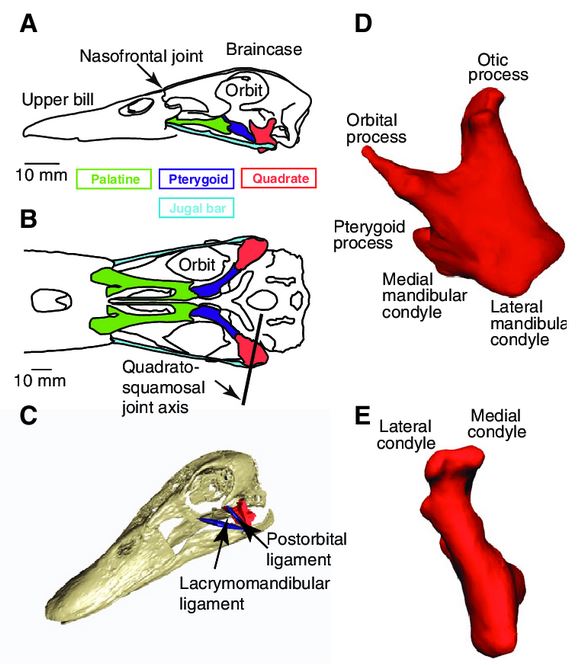

The Avian Quadrate Bone

We previously discussed the avian quadrate bone in the first and eighth posting in this series, but it doesn’t hurt to be reminded of this major marker in the early evolution of birds. You’ll never look at ducks and chickens the same way again.

Mallard skull and quadrate anatomy. (A) Lateral view, (B) Ventral view. Bones: Quadrate (red), Pterygoid (purple), Palatine (green), Jugal (blue), Upper Bill. From: Kinematics of the Quadrate Bone During Feeding in Mallard Ducks. [Link] (2011) Megan M Dawson, Keith A Metzger, David B Baier & Elizabeth L Brainerd. [Diagram used in Taxonomy 1 & 8.]

In birds and [other] reptiles, the quadrate acts as a hinge between the lower jaw and the skull and plays an important role in avian cranial movement. In a study by Kuo, Benson and Field (2023), the quadrate of 50 currently living galloanseran species were examined resulted in a reconstruction of the ancestral Galloanserae which closely approximated the average of living modern galloanserans. But when they added early fossil galloanseran quadrates to the study the results shifted, indicating that the quadrate of the common ancestor of galliforms and anserforms was closer to the quadrate of living galliforms than that of living anserforms. In short, the common ancestor of all chickens and ducks was [likely] more like a chicken than a duck. Morphology still has important things to add.

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves

The remaining 34 orders and the rest of almost 10,500 species of birds are in the Parvclass clade of Neoaves, which we will discuss as seven clades. All of these clades appeared 60-70 mya, close to the end of the Cretaceous era and start of the Paleocene era 66 mya, caused by that cataclysmic impact of an asteroid into what is now the Gulf of Mexico, north of the Yucatan peninsula. Except for the warm-blooded birds, the dinosaurs vanished and the Neoavian evolutionary radiation exploded. All dates are molecular clock calculations, based not on proteins but on ~30 million pairs of genomic (chromosomal) DNA. There are many competing systems for Neoaves phylogeny, this site shows ten of them.

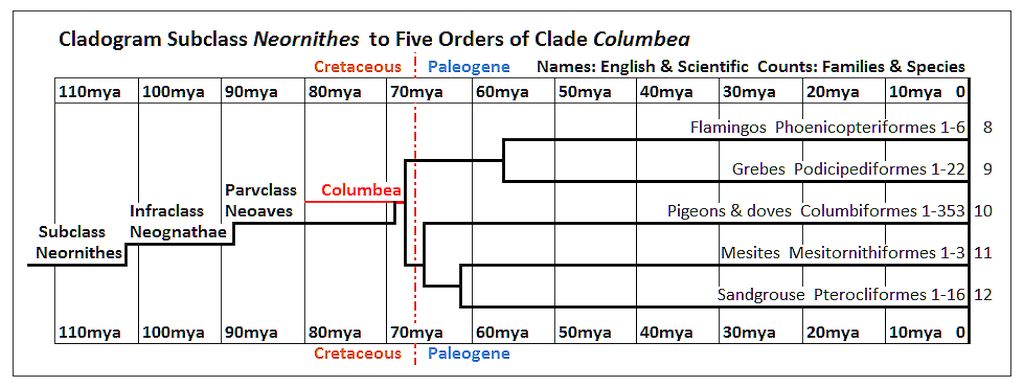

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Columbea

The Clade Columbea currently consists of 5 orders, 5 families and 400 species. Their first divergence was the widespread Phoenicopterimorphae Superorder (orders of flamingos and grebes) from Columbimorphae at 68 mya. Within Columbimorphae Order Columbiformes (Pigeons & Doves) diverged at 65 mya, followed at 62 mya by the divergence between Order Mesitornithiformes (Mesites of Madagascar) and Order Pterocliformes (Sandgrouse, ranging from east Asia to southern Africa). [Some scientists do not combine Phoenicopterimorphae and Columbimorphae into a single clade; one such alternative suggest two clades, Mirandornithes (Flamingos & Grebes) and Columbimorphae (Pigeons, Mesites and Sandgrouse) as two simultaneously emerging clades, with sister taxon Passerea containing all remaining birds. This creates a polytomy which in the current view cannot be correct.] Several of the following cladesSome scientists do not combine Phoenicopterimorphae and Columbimorphae into a single clade. Several of the following clades are larger with more divergences. If you’ve compared the text so far with the cladogram(s), you should have a feeling for the grouping and divergences and won’t need all the additional detailed descriptions as have been supplied so far. The largest family in Clade Columbea by far is Columbidae (Pigeons & Doves, 353 species). The smallest family is Mesitornithidae (Mesites of Madagascar, 3 species).

Subdesert Mesite (Monias benschi) of southwestern Madagascar.

Photo: Ben Rackstraw, Nov. 2006. Wikipedia: Mesite

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea

After the divergence of the clade Columbea, the remaining Neoaves are tentatively classified into the clade Passerea. This encompasses all the remaining 29 orders, 233 families and 10,075 species. We will discuss these as six clades.

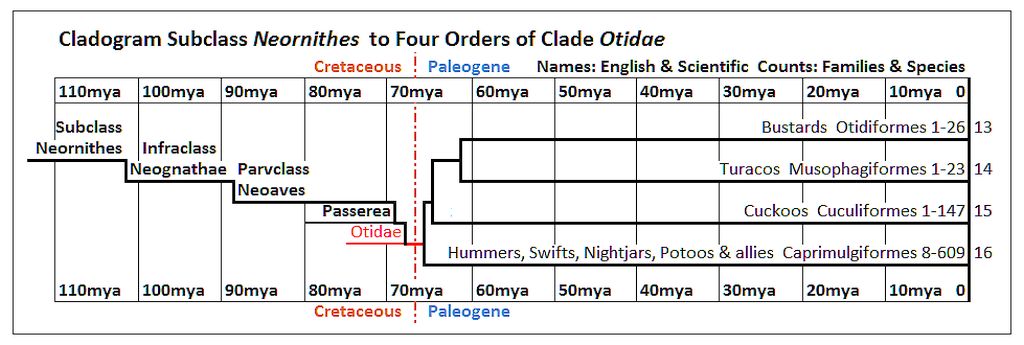

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Otidae

The first group within this large clade of Passerea consist of the Clade Otidae. This contains superorders Caprimulgimorphae & Otidimorphae, which combined comprise 4 orders, 11 families and 805 species. 609 of these species are in the Order Caprimulgiformes, an increasingly diverse order comprising 8 families: Hummingbirds, Treeswifts, Swifts, Owlet-Nightjars, Oilbird, Potoos, Nightjars and Frogmouths. Fifty years ago there were only 105 species in 5 families classified to Caprimulgiformes. These two superorders diverged from the rest of Clade Passerea 68 mya, the same time that Superorder Phoenicopterimorphae diverged from the rest of Clade Columbea (described above). With the 5% (+/- 3.4 million years) credible dates (margin of error), this was when the asteroid extinction even occurred. During the very early Paleogene (65-61 mya) this clade diverged into its current four Orders of Caprimulgiformes (Hummingbirds, Swifts, Nightjars, Potoos & allies), Cuculiformes (Cuckoos), Musophagiformes (Turacos of Sub-Saharan Africa) and Otidiformes (Bustards – widespread but uncommon in the Old World). The largest families are Trochilidae (Hummingbirds, 155 species in the Americas), Cuculidae (Cuckoos, 147 species worldwide) and Caprimulgidae (Nightjars and allies, 97 species worldwide). The only monotypic family is: Steatornithidae (Oilbird of the American tropics).

Oilbirds (Steatornis caripensis) nest and roost in caves across northern and northwestern South America.

Photo: The Lilac Breasted Roller. April 2007. Wikipedia: Oilbird

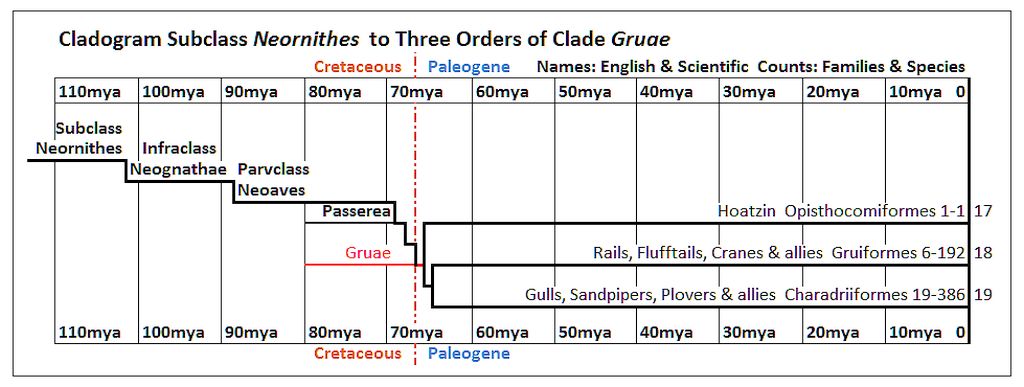

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Gruae

The clade Gruae appeared at the K-Pg extinction event, 66 mya. Within two million years it had already begun diversifying into two Superorders, Opisthocomimorphae and Gruimorphae. Opisthocomimorphae today consists of a single family Opisthocomidae with a single species (the Hoatzin of South America). Gruimorphae diverged into two orders: Gruiformes (six families of Flufftails, Coots, Finfoots, Limpkin, Trumpeters and Cranes – 192 species worldwide), and the very diverse Charadriiformes (19 families of Gulls, Sandpipers, Plovers, Alcids, Buttonquail, Pratincoles, Oystercatchers, Thick-knees and 11 other families of under ten species each – 386 species worldwide). The largest families are Rallidae (Rails, 155 species), Laridae (Gulls and allies, 100 species) and Scolopacidae (Sandpipers, 97 species). There are six monotypic families: Opisthocomidae (Hoatzin of South America), Aramidae (Limpkin So.-Cent. America), Pluvianellidae (Magellanic Plover of Southern South America), Ibidorhynchidae (Ibisbill of South Asian mountains), Pedionomidae (Plains-wanderer of eastern Australia) and Dromadidae (Crab-Plover around the Indian Ocean).

Ibisbill (Ibidorhyncha struthersii) , a bird of central Asian mountain streams.

Photo: Mohanram Kemparaju, March 2008. Wikipedia: Ibisbill

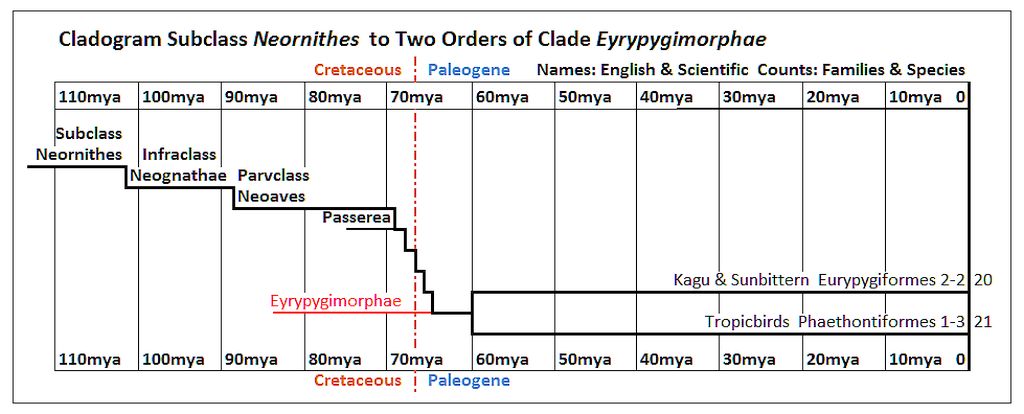

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Eurypygimorphae (or Phaethontimorphae)

Clade Eurypygimorphae is a small clade consisting of the two Orders Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes, two families and only 5 extant species. It is the sister taxon to Clade Aequornithes as their common ancestor appeared shortly after the K-Pg extinction event, and these two clades began to separate within a million years after that. The reason I denote it as a separate clade is because an important source report (Brusette, O’Conner, Jarvis 2015 The origin and diversification of birds; link) classified them as within Clade Passerea, but not within the clade of Core Waterbirds (Aequornithia), thus indicating that they were a basal clade. The two orders within this clade diverged from each other 5 million years later, or 60 mya. Order Eurypygiformes contains only the Kagu of New Caledonia and the Sunbittern of the American tropics, two widely-separated locations. Order Phaethontiformes contains three species of Tropicbirds, previously classified to the order Procellariformes next to the Pelicans.

Sunbittern (Eurypyga helias) of Central and northern South America, displaying its “suns.” Stavenn, Jan 2007. Wikipedia: Sunbittern

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Aequornithes (Core Waterbirds)

Clade Aequornithes (or Aequornithia) or Core Waterbirds consists of three sub-clades, six orders, 16 families and 365 species. Clades Aequornithes and sister taxon Eurypygimorphae diverged from the final two clades of Afroaves and Australaves, see below) very soon after the K-Pg extinction event. Aequornithes separated from Eurypygimorphae about 1 million years later. The loons then diverged, soon followed by divergence of the Stork, Cormorant and Pelican Orders from the Penguins and Tubenoses, 61 mya. Within a few million years these clades had further diversified into the six current orders. The largest families are Procellariidae (Shearwaters and Petrels – 98 species worldwide) and Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets, and Bitterns – 71 species worldwide). There are two monotypic families: Balaenicipitidae (Shoebill of Central Africa), and Scopidae (Hamerkop of sub-Saharan Africa).

Hamerkop (Scopus umbretta) of sub-Saharan Africa, southwest Arabia and Madagascar. This 1 lb. 22 inch tall bird builds one of the largest nests in the world; one was estimated to contain 8,000 sticks.

Photo: Sumeet Moghe, August 2012. Wikipedia: Hamerkop

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Telluraves (Core Landbirds)

Clade Telluraves is the sister taxon to Clade Aequornithes and has two main branches, the sister taxa of Clade Afroaves and Clade Australaves. These two clades diverged 63 mya.

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Telluraves (Core Landbirds) – Clade Afroaves

Our last two clades and sister taxa of Afroaves and Australaves diverged from one another 63 mya (+/- 3.2 my). Looking at the cladogram you’ll see that Clade Afroaves diverged up to seven more times before reaching the rank of Order. The clade’s current ten orders evolved 63-42 mya and now totals 28 families (11.2% of 251 families) and 1,254 species (11.4% of 11,017 species). [Those two percentages seem oddly similar.] The three largest families by far are: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites – 250 species worldwide), Picidae (Woodpeckers – 235 species worldwide), and Strigidae (Owls – 229 species worldwide). Three families are monotypic: Pandionidae (everyone’s favorite land-based fish-eater, the Osprey, found worldwide), Sagittariidae (the Secretarybird of sub-Saharan Africa) and Leptosomidae (the Cuckoo-roller, a Madagascar endemic). Cuckoo-Roller is the sole denizen of one of the two monotypic orders; the other is the Hoatzin of Opisthocoformes.

Cuckoo-Roller (Leptosomus discolor) of Madagascar an Comoros Islands, female or juvenile; named for its resemblance to both cuckoos and rollers.

Photo: frank wouters, October 2005. Wikipedia: Cuckoo-Roller

Subclass Neornithes – Infraclass Neognathae – Parvclass Neoaves – Clade Passerea – Clade Telluraves (Core Landbirds) – Clade Australaves

Our last clade, in some ways the most unusual, diverged from its sister clade Afroaves 63 mya (+/- 3.2 my), shortly after that infamous K-Pg asteroid strike. The small Order of Cariamiformes (Seriemas, 2 species endemic to the grasslands of central South America) diverged perhaps less than a million years later from, leaving Clade (or Superorder) Eufalconimorphae (falcons, parrots & passerines) remaining. Falconiformes (Falcons & Caracaras, 65 species worldwide, all in one family) diverged 60 mya, leaving clade Psittacopasseres, a portmanteau name encompassing the two remaining Orders of Psittaciformes and Passeriformes. As Cariamiformes and Falconiformes are more basal (closer to the root) than Psittacopasseres, it suggests that the last common ancestor of the entire clade had a predatory lifestyle. The final divergence 55 mya was between sister taxa Psittaciformes (Parrots & Cockatoos, 405 species in 4 families, worldwide) and Passeriformes. Passeriformes (songbirds) is an enormous order: a whopping 143 families [57% of 251 total families] and a stunning 6,595 species [60% of 11,017 species], 49% more species than all the 40 other orders combined). It is again interesting to note that the percentages for family and species diversity are nearly the same. The size of this order – 60% of all bird species – explains why most birders frequently speak of birds as divided into only two groups: passerines and non-passerines.

Blue-banded Pitta (Erythropitta arquata) of Borneo, a beautiful member of a beautiful and reclusive family.

Photo: JJ Harrison. Wikipedia: Blue-banded Pitta

Our next and penultimate posting in this series will focus on the huge and hugely diverse Order Passeriformes.

The Taxonomy Series

Installments post ever other day; installments will not open until posted.

Taxonomy One: A brief survey of the history and wherefores of taxonomy: Aristotle, Linnaeus and his binomial system of nomenclature, taxonomic ranks and the discovery and application of biological clocks.

Taxonomy Two: Introduces the higher levels of current taxonomy: the three Domains and the four Kingdoms. We briefly discuss Kingdom Protista, then the seven phyla of Kingdom Fungi.

Taxonomy Three: Kingdom Plantae.

Taxonomy Four: Kingdom Animalia to Phylum Annelida.

Taxonomy Five: A discussion of Cladistics, how it works and why it is becoming ever more important.

Taxonomy Six: Phylum Chordata, stopping at Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Seven: Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Eight: Class Aves, beginning with a comparison of five different avian checklists of the past 50 years.

Taxonomy Nine: A cladogram and discussion of Subclass Neornithes (modern birds) of the past 110 million years, reaching down to the current forty-one orders of birds.

Taxonomy Ten: A checklist of Neornithes including all ranks and clades down to the rank of the current 251 families of birds (plus a few probable new arrivals) with totals of the current 11,017 species of birds.

A FEW USEFUL & INFORMATIVE SITES:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aequornithes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afroaves

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australaves

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austrodyptornithes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cavitaves

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufalconimorphae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gruae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otidimorphae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passerea

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelecanimorphae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phaethoquornithes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picocoraciae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strisores

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telluraves

Discover more from SANTA MONICA BAY AUDUBON SOCIETY BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.