Domains & Kingdoms; Protista & Fungi | Taxonomy 2

[By Chuck Almdale]

Domains

The newest and highest rank of taxonomic classification is the Domain. As we will find throughout this blog series, all these taxonomic ranks and their contents are under constant revision. What is presented here is not only one snapshot in time, it is one snapshot among several snapshots of the same moment in time. Please keep that in mind. This field is in flux.

Domains of Three

The Diversity of Archaea. Photo: Maulucioni. Wikipedia – Archaea

The Diversity of Archaea. Photo: Maulucioni. Wikipedia – Archaea

1. Domain Archaea

The appropriately-named Archaea are considered the most ancient form of life on earth. The Archaea are prokaryotes (see below) because they lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. They also have biochemical and RNA markers which distinguish them from the other and better-known prokaryotes, bacteria. Archaea have very diverse metabolisms and include methanogens that produce methane, halophiles that live in very saline water, and thermoacidophiles which live in acidic high-temperature water. Some are autotrophic, some are heterotrophic. Some live in the gut of mammals. The National Library of Medicine [Link] estimates there are 20,000 species of Archaea in thirty phyla in the world. The paper “The next million names for Archaea and Bacteria” [Link] on Science Direct estimates millions to billions of species of Archaea and Bacteria, but doesn’t estimate how many of each.

Terms of Biological Nomenclature:

Nomenclature: A system for giving names to things within a particular profession or field, especially in science; e.g. “the Linnaean system of biological nomenclature.”

Taxonomy: A practice and science concerned with classification or categorization on the basis of shared characteristics, typically with two parts:

a. Taxonomy: The development of an underlying scheme of classes.

b. Classification: The allocation of things to the classes, ranks or taxa.

Taxon: In biology, a taxon (back-formation from “taxonomy”; plural: taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and given a particular ranking, especially if and when it is accepted or becomes established.

Systematics: The branch of biology that deals with classification and nomenclature.

Binomial Nomenclature: System of scientifically naming organisms with two words.

Genus: The taxonomic category above species.

Species: The most basic taxonomic category consisting of individuals who can – in the biological definition of “species” – produce fertile offspring.

Clade: A biological grouping that includes the common ancestor and all the descendants (living and extinct) of that ancestor.

Polyphyletic: When a group of organisms derive from more than one common evolutionary ancestor or ancestral group and are therefore not suitable for placing in the same taxon.

Biological Definitions:

Autotrophic: Able to produce their own food using light, water, carbon dioxide, or other chemicals; plants with chlorophyll are the best-known autotrophs.

Heterotrophic: Must eat other organisms for energy and nutrients, as do animals such as lice and humans.

Eukaryote: Organisms whose cells contain a membrane-bound nucleus, including all known non-microscopic organisms such as worms and humans. In other words, every living thing except bacteria mentioned from here on in this series.

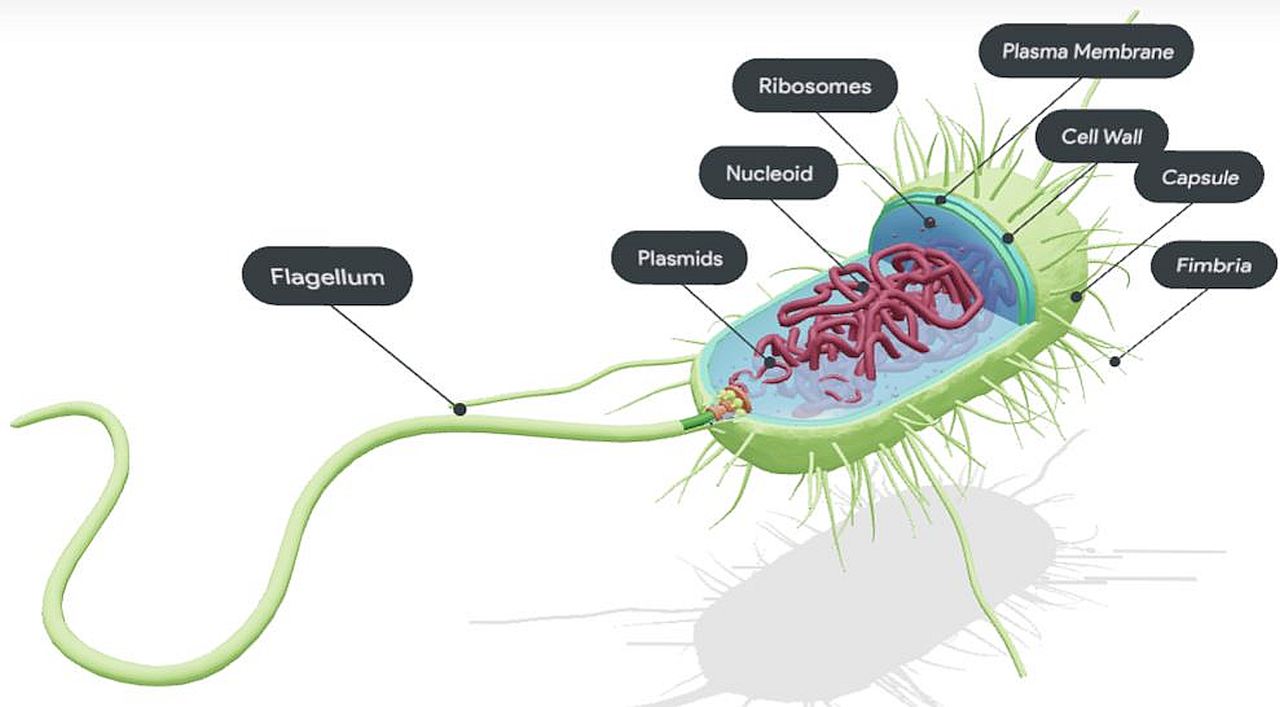

Prokaryote: Unicellular organisms lacking a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles: the Archaea and Bacteria.

2. Domain Bacteria

Bacteria are also prokaryotes but with cell membranes made of a phospholipid bilayer and differently structured RNA in their ribosomes. They range from 1-10 microns long and 0.2-1.0 micron wide (micron = micrometer = 1 millionth of a meter = ~0.00004 in.) Estimates range from 39 trillion bacteria living within our entire body to 100 trillion living just in our intestinal tract. There are over 30,000 known species of bacteria and scientists conjecture there may easily be trillions of species. All are unicellular, but some bacteria form large, non-microscopic colonies held together by biofilms, such as those growing – right now, silently – on your teeth, known as plaque. As with the Archaea, some bacteria are autotrophic and some heterotrophic. They are not extremophiles and they thoroughly enjoy sharing our environment with us, especially our intestinal tract, sinus cavities and mouth.

Typical bacteria, a prokaryote. Source: Visible Body, where it rotates in 3-D.

A few more awe-inspiring bacterial factoids from the book Think, by Guy P. Harrison:

Edward O. Wilson thought that had he one more life he would give up ants and study bacteria, and once wrote: “Ten billion bacteria live in a gram of ordinary soil, a mere pinch between the thumb and forefinger. The represent thousands of species, almost none of them known to science. Into that world I would go with the aid of modern microscopy and molecular analysis. I would cut my way through clonal forests sprawled across grains of sand, travel in an imagined submarine through drops of water proportionately the size of lakes, and track predators and prey in order to discover new life ways and alien food webs. All this, I need venture no farther than ten paces outside my laboratory.”

The bacterium Desulforudis audaxviator was found living a half mile below the surface near Death Valley, Ca., and is believed to be the same species found two miles below ground level in South Africa. They live in complete isolation in an environment that is sunless, hot (up to 140°F/60°C,), lacks oxygen and organic matter, where it lives on the by-products of radioactive decay in the surrounding rock. Researches think they sometimes ride to the surface via natural water springs, then are blown thousands of feet into the air where they are carried thousands of miles, then fall back to earth in raindrops, finally to find their way deep into the earth in a new location.

In samples of air taken twelve miles up in the upper troposphere, scientists have found more than 2100 microbial species. They appear to have their own atmospheric pathways and travel around the globe. Are they influencing our weather, or are we sharing theirs?

3. Domain Eukaryota

Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells contain a membrane-bound nucleus, including all known non-microscopic organisms such as worms and humans. In other words, every living thing mentioned in this series from this point on. The rest of this post and the following eight posts are devoted to Eukaryota.

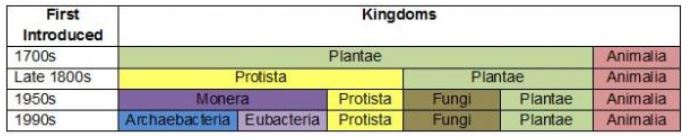

Kingdoms: From Two to Eight

The number and nature of Domains and the next level of Kingdoms are far from settled science. Depending on whom or where or when you ask, there are as few as two or as many as eight kingdoms.

Three (or two) Kingdoms

As we saw in Taxonomy One, Linnaeus described three kingdoms: Animale, Vegetabile and Lapideum (mineral). Minerals – generally considered to be non-living and non-sentient (except by crystal-worshippers) – were long ago dropped from inclusion, so Linnaeus really described two biological kingdoms.

Four (or five) Kingdoms:

Robert Whittaker’s system of 1969 described four Eukaryota Kingdoms:) Animalia (Metazoa), Plantae, Fungi and Protista. A fifth kingdom, Monera (or prokaryotes, divided into Archaea and Bacteria when discussed above) is often included, in which case the use of “Domains” become unnecessary.

Six Kingdoms

Archaebacteria, Eubacteria, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. As with five kingdoms, this eliminates “Domains” and places the Archaea (Archaebacteria) and Bacteria (Eubacteria) on the same level as the other four kingdoms. Another way of looking at it with three domains and four (eukaryotic) kingdoms – which I shall adopt – is illustrated below.

Three Domains, four Kingdoms model. Source: Texas Gateway

Seven Kingdoms

To our two prokaryotic kingdoms of Archaea (Archaebacteria) and Bacteria (Eubacteria), and our three multicellular kingdoms of Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia, this schema renames Protista (from the six kingdoms schema) to Protozoa and breaks Chromista out from Protozoa. Most Chromists, like plants, are photosynthetic and have chloroplasts. Chromista chloroplasts are located in the lumen of their rough endoplasmic reticulum, rather than in the cytosol.

Eight Kingdoms

This system was developed by British zoologist Thomas Cavalier-Smith and first appeared in 1978, but continued to be modified until Cavalier-Smith died in 2021. It included the usual six kingdoms: Archaebacteria, Bacteria (Monera), Plantae, Animalia, Fungi, Protista, plus Chromista and Archezoa. Archezoa consisted of protists that lack mitochondria (organelles that generate adenosine triphosphate, used by the cell for chemical energy.) As additional organisms were assigned to Archezoa, the taxon became polyphyletic (composed of unrelated taxa lacking a common origin). Cavalier-Smith originally considered Archezoa a Subkingdom, then elevated it to Kingdom when he described Chromista. Later he assigned the members of Archezoa members to phylum Amoebozoa and eliminated Archezoa altogether.

The evolution of evolutionary trees. Source: Texas Gateway

The four Kingdoms

With all that uncertainty in mind, from here on I’ll be using the Three Domains, Four Kingdoms model previously pictured. But not much, as from here on we never really discuss Domains again.

The four Kingdoms of Protista, Fungi, Plantae and Animalia will be considered the members of Eukaryota, the third of the three Domains. We’ll leave Kingdom Archaea (Archaebacteria) and Kingdom Bacteria (Eubacteria) within their own separate Domains.

Kingdom Protista or Protozoa

Protozoa have cell membranes, not cell walls. They have often been considered part of Kingdom Anamalia, but are now considered part of Protista, which also includes plant-like Phytotrophs, and fungus-like slime molds.

Protista consists of any eukaryotic organism other than animal, land plant, or fungus. They are all eukaryotic; most are unicellular, some multicellular; they can be autotrophic or heterotrophic. They are classified by how they move, as cilia (Paramecium), flagella (Euglena), or pseudopods (Amoeba). This is not a natural clade but a polyphyletic grouping of several independent clades that evolved from their last eukaryotic common ancestor.The term may be gradually abandoned as phylogenetic analysis and electron microscopy develop further, and the various protists are reclassified to various supergroups. There may be 60,000 – 200,000 species of protists, but many have not been described.

Kingdom Fungi

All fungi are eukaryotic and heterotrophic, most are multicellular, but some are unicellular (yeast). They used to be considered plants. However, nearly all fungal cell walls contain chitin which also forms the exoskeletons of many invertebrate animals. Additionally, Chytridiomycota (1st phylum below) zoospores and animal sperm both have a single posterior flagellum. Some scientists consider them sister clades and classify them into a common ancestor Opisthokont clade (opistho posterior + kont flagellum). Fungi examples: Mushrooms, mold, mildew, ringworm. Estimates of total fungi species range from 1.5 million to 11 million, but only 150,000 species have been described. As usual, there are various systems of organizing fungi; we’ll present a British system which contains seven phyla.

Fungi definitions:

Coenocytic: A multinucleate mass of protoplasm resulting from repeated nuclear division unaccompanied by cell fission.

Diploid: Having two sets of chromosomes in a cell (as do humans).

Flagella: Slender threadlike structures that enable many protozoa, bacteria, spermatozoa, etc. to swim.

Haploid: Having a single set of chromosomes in a cell (as with spermatozoa and unfertilized ova).

Meiosis: Cell division resulting in four daughter cells each with half the number of chromosomes of the parent cell, as in the production of gametes and plant spores.

Meiospore: A haploid spore resulting from meiosis.

Mycelia: The mass of branched, tubular filaments (hyphae), making up the thallus, or undifferentiated body, of a typical fungus.

Mycorrhiza, an intimate association between the branched, tubular filaments (hyphae) of a fungus and the roots of higher plants.

Saprotrophic: Taking in nutrients in solution form from dead & decaying matter.

Zygote: A diploid cell resulting from the fusion of two haploid gametes; a fertilized ovum.

Zygotic Meiosis: A diploid zygote (e.g. fertilized ovum) undergoes meiosis to produce haploid cells forming multicellular haploid individuals (as with slime molds).

1. Phylum Chytridiomycota: Mainly aquatic, some are parasitic or saprotrophic; unicellular or filamentous; chitin and glucan cell walls; primarily asexual reproduction by motile spores (zoospores); mycelia; contains two classes totaling about 1,000 species. Wikipedia – Chytridiomycota

Synchytrium endobioticum on potatoes.

Photo: USDA-APHIS-PPQ. Wikipedia: Chytridiomycota

2. Phylum Neocallimastigomycota: Anaerobic fungi found in digestive tracts of herbivorous mammals, reptiles and humans; zoospores with one or more posterior flagella; lacks mitochondria but contains hydrogenosomes (hydrogen-producing, membrane-bound organelles that generate energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate, or ATP). One class with roughly 36 species. Wikipedia – Neocallimastigomycota

3. Phylum Blastocladiomycota: Parasitic on plants and animals, some are saprotrophic; aquatic and terrestrial; flagellated; alternates between haploid and diploid generations (zygotic meiosis); contains 1 class with less than 200 species. Wikipedia – Blastocladiomycota

Plant leaf with Physoderma menyanthis (former Cladochytrium menyanthis) signs. Photo: James Lindsey. Wikipedia: Blastocladiomycota

4. Phylum Microsporidia: Spore-forming parasites formerly thought to be protozoans or protists. The spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical (highest point of a shape) part of the spore. 1,500 species named out of probably more than one million species. Wikipedia – Microsporidia

Microsporidan Glugea stephani is a common parasite in the intestines of dab (Limanda limanda). Picture taken from a dab from the Belgian continental shelf. Photo: Hans Hillewaert Wikipedia: Microsporidia

5. Phylum Glomeromycota: Forms obligate, mutualistic, symbiotic relationships in which hyphae penetrate into the cells of roots of plants and trees (arbuscular mycorrhizal associations); coenocytic hyphae; reproduces asexually; cell walls composed primarily of chitin. Approximately 230 species named. Wikipedia – Glomeromycota

Gigaspora margarita in association with Lotus corniculatus.

Photo: Mike Guether Wikipedia – Glomeromycota

6. Phylum Ascomycota – Sac Fungi: The largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The “ascus” is a microscopic sac in which nonmotile spores are formed. Includes morels, truffles, brewer’s and baker’s yeast, cup fungi, and are symbiotic with algae to form lichens. Wikipedia – Ascomycota

Sarcoscypha coccinea: shown is the ascocarp, a “fruit body.”

Photo: User:Velela Wikipedia – Ascomycota

7. Phylum Basidiomycota – Filamentous fungae: Most species composed of hyphae and reproducing sexually via specialized club-shaped cells called basida that normally bear four external meiospores. Includes: agarics, puffballs, stinkhorns, jelly fungi, boletes, chanterelles, smuts, rusts, and Cryptococcus (human pathogenic yeast). Around 31,000 species Wikipedia – Basidiomycota

Common Stinkhorn Phallus impudicus, one of the Basidiomycota.

Photo: Birger Fricke. Wikipedia – Phallaceae

This is by no means the only system for fungi. Another system reduces Microsporidia in rank within Superphylum Opisthosporidia, and moves two incertae sedis (“of uncertain placement,” see below) taxa, Subphyla Zoopagomycotina and Subphyla Mucroromycota (both currently within Phyla Glomeronycota), into full phyla status, for a total of nine phyla.

8. Phylum Zoopagomycotina: Endoparasitic (lives in the body) or ectoparasitic (lives on the body) on nematodes, protozoa, and fungi; thallus branched or unbranched; asexual and sexual reproduction. Approximately 1,000 species.

9. Phylum Mucoromycotina: Parasitic, saprotrophic, or ectomycorrhizal (forms mutual symbiotic associations with plants); asexual or sexual reproduction; branched mycelium. Approximately 325 species.

Book Source

Think: Why You Should Question Everything, Guy P. Harrison; 2013, Prometheus Books, Amherst, NY. Pgs. 195-196

The Taxonomy Series

Installments post ever other day; installments will not open until posted.

Taxonomy One: A brief survey of the history and wherefores of taxonomy: Aristotle, Linnaeus and his binomial system of nomenclature, taxonomic ranks and the discovery and application of biological clocks.

Taxonomy Two: Introduces the higher levels of current taxonomy: the three Domains and the four Kingdoms. We briefly discuss Kingdom Protista, then the seven phyla of Kingdom Fungi.

Taxonomy Three: Kingdom Plantae.

Taxonomy Four: Kingdom Animalia to Phylum Annelida.

Taxonomy Five: A discussion of Cladistics, how it works and why it is becoming ever more important.

Taxonomy Six: Phylum Chordata, stopping at Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Seven: Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Eight: Class Aves, beginning with a comparison of five different avian checklists of the past 50 years.

Taxonomy Nine: A cladogram and discussion of Subclass Neornithes (modern birds) of the past 110 million years, reaching down to the current forty-one orders of birds.

Taxonomy Ten: A checklist of Neornithes including all ranks and clades down to the rank of the current 251 families of birds (plus a few probable new arrivals) with totals of the current 11,017 species of birds.

Discover more from SANTA MONICA BAY AUDUBON SOCIETY BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.