Five Avian Checklists, 1965-2024 | Taxonomy 8

By Chuck Almdale

Charles Sibley & Burt Monroe 1990 || James Clements, 6th Ed. 2007

The Five Checklists

We’ll now shine some light on avian checklist changes over the past fifty years by looking at five checklists of birds dating from 1975 to 2024, focusing largely but not exclusively on the taxonomic rank of Order. For each of the five checklists the chart below lists the Orders and the number of Families and Species in each of the forty-one Orders. As such, this chart is more about the recent evolution of information about birds and its presentation than it is about the evolution of birds themselves. These checklists were, and are, snapshots in time; research continues and new information appears at a lightning pace compared to past centuries and decades. As it filters down to we non-professionals, avian systematics is likely to produce significantly changed sequences within a year or two. With that in mind, we’ll look atthese five snapshots of recent avian history. From here on the comments will refer to the chart below and won’t make much sense without referring frequently to it.

Sibley & Monroe, 1990

Charles Sibley and Burt Monroe’s book was a radical departure from prior (and some later) checklists of birds which were based entirely on morphology, and a foreshadowing of what was to come. Briefly, S&M used the most recent AOU information on what were recognized species, then adjusted the higher ranks (order, family and possibly genus) to the results of their DNA-DNA hybridization experiments, “to compare the genomes of birds for evidence of the branching pattern of avian phylogeny,” as Sibley writes in his Preface. The book contained information on habitats, ranges and subspecies, discoverers and discovery dates, name changes and variants and much more; it was far more than a bare-bones checklist. The table of contents functioned as a branching checklist and introduced new (to me, at least) ranks such as Parvorder and Subfamily, mentioned in prior installments of this series. I was impressed by this work and in February 1990, reviewed/commented on it for the Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society newsletter, The Imprint, from which I’ll take the liberty of quoting myself (with author’s consent). At that time the author could not assume that his audience had any familiarity whatsoever with DNA structure, nor any means to easily gather it. [World Wide Web, Google, Wikipedia – what’s that?] Our general familiarity with DNA structure and tinkering with it is far better now.

The field is called DNA-DNA Hybridization. This is how it works in a nutshell. They take a chromosome from the nucleus of a bird cell and heat it up. At a particular temperature it will unwind from its naturally coiled state and split apart lengthwise. Sort of like sawing a ladder in half by cutting all the rungs down the middle, only this ladder has about a half a million rungs. They repeat this process with a functionally identical chromosome from a different species of bird. Then they take the ‘left’ half from the first chromosome and the ‘right’ half from the second chromosome, put them together lengthwise, and let them cool down. Where a molecular ‘ladder rung’ on the left chromosome matches one on the right an electronic attraction is created and the two halves stick together. This new ‘hybridized’ strand of DNA is reheated, and when the halves separate again, the exact temperature is carefully noted. This temperature will always be lower than that needed for the original separation, as the hybrid will always have fewer rungs connected and will be easier to separate. A comparison of these two temperatures of separation will reveal a ratio that indicates how closely matched the chromosomal halves are. The closeness of the match indicates how closely related the species are. Thus, a high temperature of hybrid DNA separation = a more complete ladder = a close match of DNA strands = closely related species. Conversely, a low temperature = distantly related species.

They’ve taken a number of DNA samples from 1058 species of birds, doing multiple hybridizations of the same pairing of species to try to eliminate flukes and errors, kept track of all those temperatures, and compared the numbers to figure out if species #1 is more closely related to species #2 than to #3, and how #4 and #5 fit into the resulting scale. It’s time consuming work.

Time consuming indeed, as by the time the book was published Charles Sibley and John Ahlquist had been working on their hybridization experiments for fifteen years. Towards the end of the piece, I summed up my thoughts as follows, with which – 34 years later – I still agree; with 20-20 hindsight, they seem obvious.

Keep in mind that these are proposed changes, based on the DNA-DNA hybridization research. It will take years of arguing among the researchers and experts before any of these changes are officially recognized. Some of the research may prove to be incomplete or incorrect. New methods – faster or more accurate – of genetic research may be discovered. These conclusions may prove to be based on inadequate sampling, and more advanced methods may come up with different familial relationships. But one thing is certain: changes will come and there will be big surprises in store for us.

Changes certainly came; they’re still coming. Improvements in speed and accuracy were certainly made. Arguments certainly still rage, and surprises keep arriving. But Sibley & Monroe and Ahlquist’s work was groundbreaking. A great deal of work since then have brought the changes and results we will now begin reviewing. S&M&A’s work 1975-1990 produced a “snapshot in time.” The equipment improved, more snapshots were taken, and what you’re now reading is itself a snapshot in time of snapshots in time. Change will continue. Be prepared for updates.

Definitions

Nomenclature: A system for giving names to things within a particular profession or field, especially in science; e.g. “the Linnaean system of biological nomenclature.”

Systematics: The study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time.

Taxonomy: A practice and science concerned with classification or categorization on the basis of shared characteristics, typically with two parts:

a. Taxonomy: The development of an underlying scheme of classes.

b. Classification: The allocation of things to the classes, ranks or taxa.

Top to bottom the following chart presents forty-one Orders of birds in what is currently believed to be the sequence of their earliest appearance on earth. This sequence comes from eBird/Birds of the World (BOW, online) as of 4/15/24; the data from the BOW checklist is presented in the rightmost chart column. These forty-one Orders fall into nine major Clades, grouped vertically down the chart. This sequence of Clades and Orders follows the cladogram to be presented in Taxonomy 9.

The four columns to the left are the four earlier checklists presented in date order left-to-right. It is important to note that all five checklists list the Orders using the same 4/15/24 top-to-bottom sequence. The four earlier checklists may have used a slightly different phylogenetic sequence for their Orders and they didn’t all have the same orders or same number of orders. Comparison between checklists would be impossibly complicated had I left each list in their original sequence.

At the top and bottom are checklist totals for orders, families and species for each checklist. Except for species numbers, the changes between checklists largely reflect the enormous changes due to DNA research during the past ten years. The changes in totals of species reflect both the discovery of new species as well as the raising of known subspecies to full species status.

Deciphering Changes Between Checklists

41 Orders: Numbered in the left column. There was little change 1975 to 2013, then a 46% increase from 28 orders (2013) to 41 (2024) orders. This was due to the ever-more-swiftly-growing mountain of information from molecular and DNA studies and the application of evolutionary clocks. Five previous Orders disappeared from the 2024 checklist and their members redistributed to other Orders; these vanished Orders have red letters A-E in the left column.

251 Families: There were two major changes: 40% increase in families (145 to 203) from 1990 to 2007, and 24% increase (203 to 251) from 2013 to 2024, for a net 58% increase in families 1975 to 2024. The reasons are the same as above.

11,017 Species: Two major changes: 7.6% increase (8,984 to 9,669, or increase of 685) from 1975 to 1990, and 9.7% increase (10,039 to 11,017 or increase of 978) from 2013 to 2024; the total increase 1975-2024 was 23%, or 2,033 species. New species are discovered yearly, but I suspect (I haven’t done the math) is the result of of raising subspecies to full species status. Biological clock data has undoubtedly contributed to this raising of rank.

To print or save an image of the chart: click here.

Chart Size Increase: <Control> +; Decrease: <Control> -.

The Nine Clades and Forty-one Orders

Clade Infraclass Palaeognathae: “Old Jaw.” This most ancient of clades saw little change between checklists, except that prior to 2024 the first four orders were classified as families within the single order of Struthioniformes. The rest of the ~11,000 extant birds are in its sister taxon Infraclass Neognathae “new jaw.” These sister taxa diverged over 100 million years ago. [Dates listed here will be made visibly apparent in the next posting’s cladogram; they’re mentioned here for anyone wondering about this. All these dates are +- 5% accurate, or so the researchers hope.]

Elegant Crested Tinamou (Eudromia elegans), Argentina.

Photo: Dominic Sherony. Wikipedia: Tinamou

Clade Infraclass Neognathae: Neognathae (“New Jaw”) is the sister taxon to Infraclass Palaeognathae, containing the rest of the ~11,000 extant bird species.

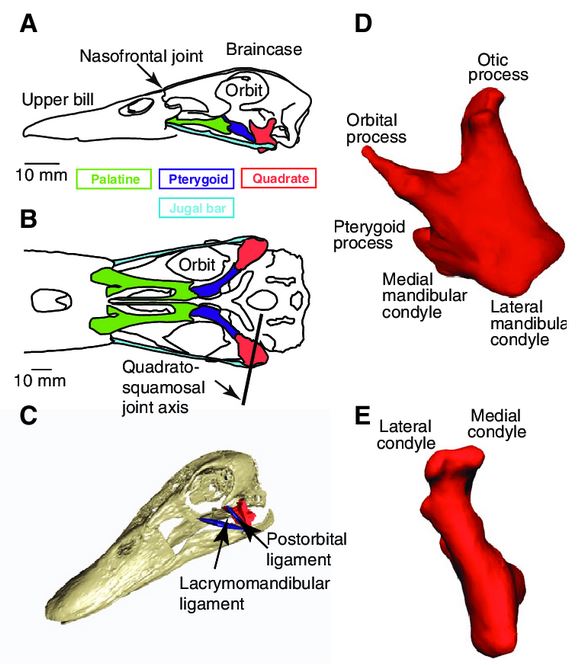

Mallard skull and quadrate anatomy. (A) Lateral view, (B) Ventral view. Bones: Quadrate (red), Pterygoid (purple), Palatine (green), Jugal (blue), Upper Bill. From: Kinematics of the Quadrate Bone During Feeding in Mallard Ducks. [Link] (2011). Megan M Dawson, Keith A Metzger, David B. Baier & Elizabeth L. Brainerd. [Diagram used in Taxonomy 1.]

Clade Superorder Galloanseres: 88 million years ago Neognathae split into two clades, Parvclass Neoaves and Superorder Galloanseres. “Galloanseres” is a portmanteau name, increasingly common in clade nomenclature, formed by combining the names of the ranks below, in this case Galliformes (chickens) and Anseriformes (ducks). Species numbers fluctuated over the past 50 years, starting at 420 and ending at 483, most of that increase occurring within the past 10 years. Sibley & Monroe (1990) added two orders, a move few others accepted. Members of the Orders Craciformes and Turniciformes were reclassified to Galliformes. The study of the quadrate bone in jaws of all reptiles and birds led to discoveries that 1) Anseriformes (ducks & allies) and Galliformes (chickens & allies) were each other’s closest relatives, and 2) they were a basal clade, closer to their reptilian ancestors than all other Neognathae members.

The cryptic Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata), a megapode of Australia.

Photo: Kerry Raymond. Wikipedia: Malleefowl

Clade Parvclass Neoaves: Neoaves is the sister taxon to Superorder Galloanseres, containing the rest of the 10,480+ extant bird species.

Clade Columbea: Order Mesitornithiformes (the 3 mesite species of Madagascar) was recently moved to this group. Total species jumped from 349 in 2013 to 400 in 2024, almost entirely due to a 14% rise (44 species) in the pigeons and doves. I don’t know the cause but my best guess is raising subspecies to full species status, especially in Southeast Asia. This clade split from the Neoaves 69 million years ago. The Pterocliformes (Sandgrouse) Order moved around a bit; for example, Sibley & Monroe considered them part of the Stork Order Ciconiiformes in 1990.

Superb Fruit-Dove (Ptilinopus superbus): Cape York, Queensland, Australia. Photo: Roger MacKertich. Wikipedia: Superb Fruit-Dove

Clade Passerea: Passerea is the sister taxon to Clade Columbea, containing the rest of the 10,080+ extant bird species in five subsidiary clades: Otidae, Gruae, Eurypygimorphae, Aequornithes (Core Waterbirds) and Telluraves (Core Landbirds). Telluraves has two major subsidiary clades: Afroaves and Australaves.

Clade Passerea: Clade Otidae: A lot of shifting around has occurred within this clade. Total species drifted up and down and up with a net 19% increase: 676 (1975) to 805 (2024). Otidiformes (Bustards) was raised from Family rank within Gruiformes (Cranes & allies) to its own Order. The Musophagiformes (Turacos) Order appeared in 1991, disappeared in 2007, then reappeared in 2024. The Orders of Apodiformes (Swifts) and Trochiliformes (Hummingbirds) were split apart in 1990, recombined in 2007, then both Orders disappeared in 2024, gobbled up by the expanding Caprimulgiformes (Nightjars & allies) Order, within which they now rank as families. This is one of the many clades that diverged around the time of – or shortly after – the Cretaceous-Paleogene asteroid extinction event 66 million years ago. Life on earth was tossed up into the air; when it settled back down, nothing looked the same.

Guinea (or Green) Turaco (Tauraco persa); west Africa.

Photo: Ian Wilson. Wikipedia: Turaco

Clade Passerea: Clade Gruae: The major change in this clade occurred in 1990 when Sibley & Monroe reclassified gulls, sandpipers and allies to the Order Ciconiiformes (Storks), together with many other families and orders previously scattered around the sequence. This was all undone, and Ciconiiformes is currently in Clade Aequornithes, farther down. The monotypic Hoatzin (Opisthocomiformes) had long been considered most closely related to Cuculiformes (Cuckoos) in Clade Otidae immediately above. Other than these ins and outs, total species 1975-2024 increased only 8%, from 535 to 579. As with Clade Otidae, Clade Gruae also appeared in the 66-60 mya period.

The nearly flightless Guam Rail, locally the ko’ko’ (Hypotaenidia owstoni), extinct in the wild, surviving only in captivity. Photo: Greg Hume. Wikipedia: Rail

Clade Passerea: Clade Eurypygimorphae: Although this clade – so tiny it barely exists, consisting only of Eurypygiformes (the Kagu of New Caledonia and the Sunbittern of South America) and the three species of Phaethontiformes (Tropicbirds) – diverged from the far larger Aequornithes line about 65 mya, this relationship was not recognized until recently, thanks to evolutionary clocks. For example, Sibley & Monroe (1990) classified them all to their massive Order Ciconiiformes (Storks & allies) which contained 1,027 species, with Sunbittern placed closest to Cranes and Tropicbirds closest to Hawks. In 2007, Clements classified both Kagu and Sunbittern to the Order Gruiformes (Cranes & allies) next to Finfoots and Seriemas, and Tropicbirds were with the Tubenoses (albatrosses, shearwaters, etc.) in Procellariiformes where they were placed between Diving-Petrels and Pelicans. Since then Seriemas has moved most radically; no longer a gruiform, they now have their own order and are considered to be most closely related to Falcons (see Clade Australaves below).

Kagu (Rhynochetos jubatus), a monotypic family of New Caledonia.

Photo: JJ Harrison. Wikipedia: Kagu

Clade Passerea, Clade Aequornithes (Core Waterbirds): Aequornithes diverged from the previous clade Eurypygimorphae 65 mya, and began diversifying 3 million years later into what has become six orders currently totaling 365 species. The main “bump” was Sibley & Monroe’s vast expansion in 1990 of the Stork Order Ciconiiformes, later undone by everyone. The cormorants, boobies, etc. were recently raised to their own order Suliformes after spending forever within Pelecaniformes. Pelicaniformes rose to 117 species in 2024 largely because Ciconiiformes was reduced to only the Storks (20 species), even though Pelicaniformes lost the three species of Tropicbirds, now classified to their own Order Phaethontiformes. Total 1975 species of 307 increased only 19% (58 species) to 365 in 2024, most of that increase in the Tubenose order of Procellariiformes.

Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex), specializes in eating lungfish, central Africa. Photo: Hans Hillewaert. Wikipedia: Balaenicipitidae

Clade Telluraves (Core Landbirds), Clade Afroaves: Afroaves and Australaves are sister clades within Telluraves, appearing and diverging three million years after the CP (or KT) extinction event. All the basal clades of Afroaves are predatory birds and it is presumed the last common ancestor of the clade was itself a predator. One major recent change is that Hawks (formerly in Falconiformes, now in Acciptriformes) and Falcons were placed in separate orders, with Falconiformes now moved next to Parrots and Passerines as their closest relatives, while the hawks stayed in Clade Afroaves. The Cuckoo-Roller of Madagascar, previously a monotypic family within the Kingfisher Order Coraciiformes, is now the monotypic Order Leptosomiformes. Hornbills, Hoopoes and allies, which gained their own order in 1990 only to lose it by 2007, were also broken out of Coraciiformes and placed in their own Order Bucerotiformes, still in the same clade. Some experts classify Galbuliformes (Puffbirds & Jacamars) not as an Order but as two families within Coraciiformes (Kingfishers & allies). Overall species numbers rose significantly from 767 in 1975 to 1,254 in 2024, or 487 species (64%). Some of that increase is an artifact of families moving between orders.

Spotted Puffbird (Bucco tamatia) of Brazil.

Photo: Hector Bottai. Wikipedia: Spotted Puffbird

Clade Telluraves (Core Landbirds), Clade Australaves: Australaves, the last of our major clades, appeared with its sister clade Afroaves 63 mya, and very quickly (1 million years, which is nothing on the evolutionary scale) diverged with the appearance of the ancestor of Order Cariamiformes (the two Seriema species of the central South American grasslands). Previously everyone classified the Seriemas with the Cranes. The Parrots and Passerines split from the Falcons 60 mya, then split from each other five million years later. Parrots and Falcons certainly flourished since then, but nothing like the Passerines. A few numbers will illustrate the passerine expansion:

- Passerine portion of all avian species: 1975 – 5,265 (59%), 2024 – 6,595 (60%).

- Increase in Passerine species from 1975 to 2024: 1,330 (25%).

- Increase in total species 1975 (8,984) – 2024 (11,017): 2,033 (23%)

- Passerine portion of total avian increase: 65%

- Increase in total avian families 1975 (159) – 2014 (251): 92 families (58%)

- Increase in Passerine families 1975 (60) – 2024 (143): 83 (138%)

- Passerine portion of total increase in number of families: 90%

For those who have ever wondered why birders frequently divide ‘passerines’ (a single order) from ‘non-passerines,’ (forty orders) this is why.

Red-legged Seriema (Cariama cristata), predator of the grasslands of central South America; 28-35” high, capable of flight but prefers to walk or run at which it is quite proficient. Seriemas and falcons diverged 64 million years. Photo: Whaldener Endo. Wikipedia: Cariamiformes

I reiterate that it’s not the birds themselves that have changed or increased, it’s our knowledge of them that has changed and the resulting systemic reorganization brought by this new knowledge. The Falcons themselves didn’t exchange their former close relationship with hawks to snuggle up with the Parrots, who had similarly abandoned the Doves and Cuckoos to climb into bed next to the Passerines. It’s humans who discovered that they’d been wrong for centuries, that the conclusions they’d reached based entirely on morphology were not always correct – although they were mostly correct – and that proteins and DNA were capable of providing a more detailed and accurate lineage, a lineage that included the special bonus of an evolutionary clock. Convergent evolution –when two species with quite different ancestral lineages come to look like one another because they’re behaving similarly in similar habitat – can fool the best of us.

What has recently been the most noticeable change to the everyday checklists we everyday birders use in our everyday birding is this proximity of these final three orders – Passeriformes (Passerines), Psittaciformes (Parrots) and Falconiformes (Falcons) – to one another. Suddenly we found parrots and falcons, not where we all knew they belonged much earlier in the taxonomic sequence, but right next to flycatchers. That’s ridiculous! Who decided this? Well, the birds “decided” it sixty-five to fifty-five million years ago. We just now deciphered the message they left, encoded in their – and our – proteins and DNA.

We live in interesting and exciting times.

The Taxonomy Series

Installments post ever other day; installments will not open until posted.

Taxonomy One: A brief survey of the history and wherefores of taxonomy: Aristotle, Linnaeus and his binomial system of nomenclature, taxonomic ranks and the discovery and application of biological clocks.

Taxonomy Two: Introduces the higher levels of current taxonomy: the three Domains and the four Kingdoms. We briefly discuss Kingdom Protista, then the seven phyla of Kingdom Fungi.

Taxonomy Three: Kingdom Plantae.

Taxonomy Four: Kingdom Animalia to Phylum Annelida.

Taxonomy Five: A discussion of Cladistics, how it works and why it is becoming ever more important.

Taxonomy Six: Phylum Chordata, stopping at Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Seven: Class Mammalia.

Taxonomy Eight: Class Aves, beginning with a comparison of five different avian checklists of the past 50 years.

Taxonomy Nine: A cladogram and discussion of Subclass Neornithes (modern birds) of the past 110 million years, reaching down to the current forty-one orders of birds.

Taxonomy Ten: A checklist of Neornithes including all ranks and clades down to the rank of the current 251 families of birds (plus a few probable new arrivals) with totals of the current 11,017 species of birds.

Discover more from SANTA MONICA BAY AUDUBON SOCIETY BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.